After the public disclosure of alleged forced sterilisations during a family planning campaign, municipalities in Peru with more victims exhibited a steep decline in public health services and lower levels of trust in public institutions

Editor's note: This article originally appeared on VoxEU.

Trust in government is a key driver of the effectiveness of public policies, since it affects the demand for public goods and services. However, there is recent and increasing concern that citizens around the world have declining trust in institutions such as public health agencies, private corporations, scientists, or vaccine manufacturers.

If trust is essential for prosperity, what are the causes behind this trend of growing mistrust? This is a pressing question because most of our global challenges require coordination and trust between economic agents, social actors, and political institutions. Bargain and Aminjonov (2021) show that trust in the government was a strong predictor of compliance with lockdown measures in Europe during 2020. Blanchard-Rohner et al. (2021) examine whether early failures in the provision of adequate emergency care can explain vaccine hesitancy in the UK. The authors show that quality and effectiveness of emergency care predict later willingness to get vaccinated against COVID-19.

In a new paper (León-Ciliotta et al. 2023), we examine how government actions in the implementation of public programmes can shape trust in related institutions and, in turn, affect demand for public services and relevant welfare outcomes. We shed light on this question by studying the short- and long-term effects of a large-scale family planning campaign that took place in Peru in which some claim that human rights violations took place.

The nationwide family planning campaign

Alberto Fujimori’s second presidential term ran from 1995 to 2000. In 1996, his authoritarian government launched a large-scale family planning programme to cut down fertility and poverty rates. At that time, the programme was portrayed as an anti-poverty initiative that aimed to improve reproductive rights through better access to modern contraceptives, including male and female sterilisations. The programme was naturally targeted to areas where fertility was highest, which coincided with places where the most vulnerable population was located (poor municipalities, low education levels, rural, and non-Spanish speakers). Its implementation had severe (and some claim, systematic) failures, as many sterilisations were allegedly performed without proper consent, with insufficient information on the irreversible nature of sterilisation, or under threats or bribes.

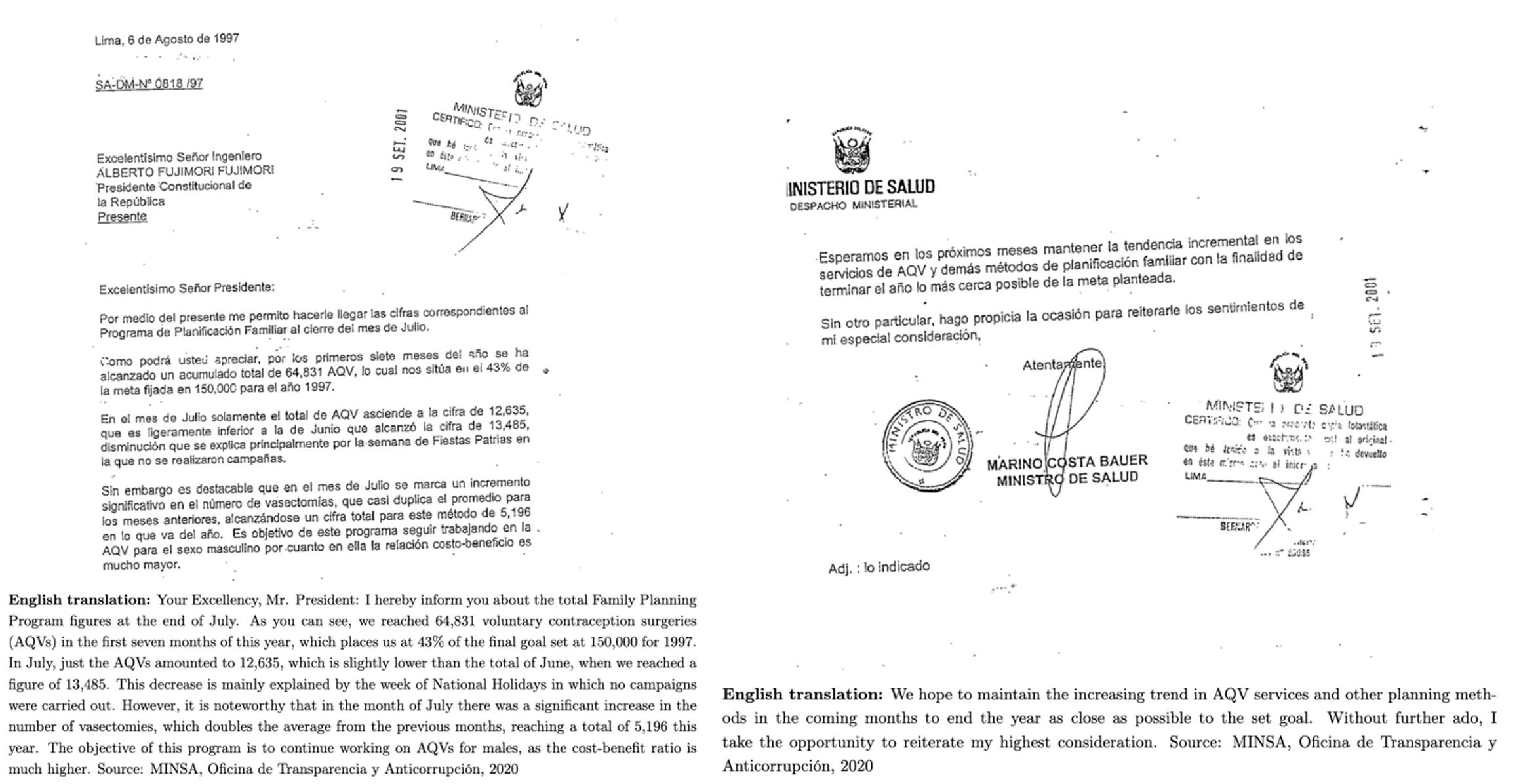

The programme was a top priority for the administration, as revealed by official correspondence between the Minister of Health and Fujimori. Every month, the minister had to report directly to the president on whether the targets of sterilisations had been met and, if not, he had to explain any delay (see Figure 1).1 Besides these ambitious targets, the government had enacted legal reforms to waive doctors’ right to object treatment or certain procedures. The regime also had control of the media and other institutions; therefore, initial reports of alleged mistreatments were quickly dismissed.

Figure 1 Letter from the Minister of Health to President Alberto Fujimori

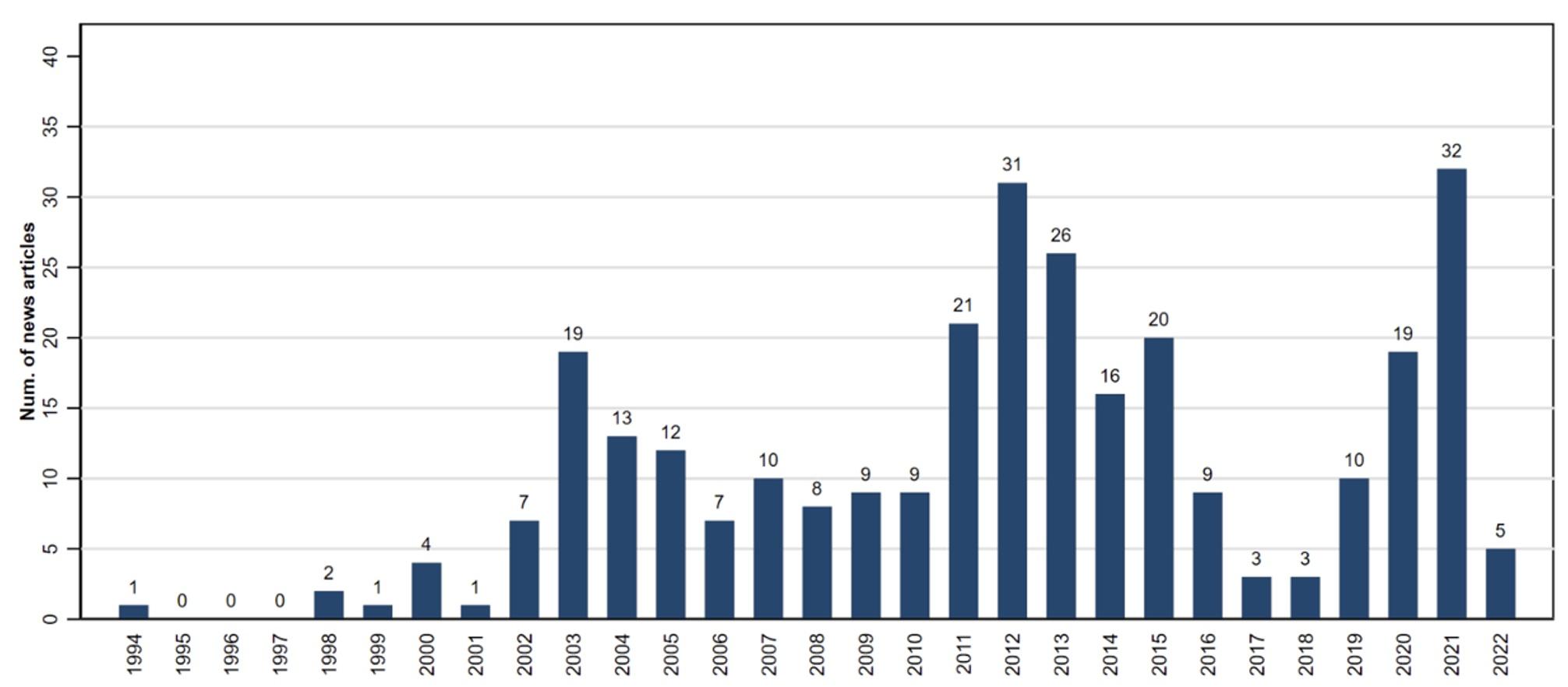

The implementation failures of the programme (i.e. violations of medical and ethical guidelines) were made public after the fall of the authoritarian regime, in late 2000 (Figure 2). In particular, the disclosure of alleged forced sterilisations occurred when the newly elected government and Congress started looking into the matter, leading to a constitutional indictment in 2001 that triggered widespread media coverage and public discussion on the violations. It also set the legal precedent for the creation of the National Registry of Victims of Forced Sterilizations in December 2015 by the Ministry of Justice. We use these newly collected data to explore whether affected municipalities have lower demand for public services that can be explained by lower trust levels.

Figure 2 Number of news articles including "forced sterilizations + Peru", by year

Note: The figure shows the total number of news articles containing the words "forced sterilization + peru" in the Factiva database.

Lower trust reduces demand for public services, leading to worse health outcomes

Using a variety of empirical methods, we show that after the public disclosure of alleged forced sterilisations, municipalities with more victims have lower demand for contraceptive methods and are less likely to use prenatal care and birth delivery services. These reductions in health care utilisation translate into worse child health. Moreover, we show that in these municipalities, there is a steep decline in the demand for public health services. Interestingly, all these effects are present even 17 years after the information disclosure.

In addition, the revelation of alleged human rights violations eroded citizens’ trust in affected districts. We also show that citizens in districts with more victims exhibit lower levels of trust in public institutions. Using electoral data, we find that, after the disclosure, districts with more victims have lower vote shares for Fujimori’s party in municipal elections.

These results show that the disclosure of alleged forced sterilisations generated mistrust and disbelief in the institutions involved in the programme or that failed to take actions against authorities in command of the programme. Moreover, the persistence of the impacts indicates that errors made by a particular public administration have long-term consequences as citizens stop trusting government institutions altogether. In other words, policy implementation failures can break down the social contract between citizens and their government.

Political disappointment, the demand for public services and trust

What are the mechanisms driving the declines in health care use (contraceptive methods, prenatal care and birth delivery services)? Using additional data, we show that municipalities with strong support for Fujimori’s party at baseline are driving the reductions in demand for health services. This result indicates that reductions in demand for public services are not driven by social learning based on identification, as in other settings (Alsan and Wanamaker 2018, Martinez-Bravo and Stegmann 2021, Lowes and Montero 2021). Instead, mistrust emerges from disappointed voters who initially supported a government that tackled several economic and social issues but also misled their citizens with a public health program where thousands of women lost their ability to have children. Learning about these violations had long-lasting consequences not only for the party and public institutions but also for children of women in affected municipalities.

We tend to think of policy failures as programmes that do not achieve their stated goals. Here, we highlight the importance of failures in the implementation of public programmes and how they can lead to long-term erosion of citizens’ trust, even after the responsible administration has left public office.

References

Alsan, M and M Wanamaker (2018), “Tuskegee and the health of black men”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 133(1): 407–455.

Bargain, O and U Aminjonov (2020), “Trust and Compliance with public health policies in the time of COVID-19”, VoxEU.org, 23 October.

Blanchard-Rohner, G, B Caprettini, D Rohner and H J Voth (2021), “From tragedy to hesitancy: How public health failures boosted COVID-19 vaccine scepticism”, VoxEU.org, 1 June.

León-Ciliotta, C, D Zejcirovic and F Fernandez (2023), “Policy-Making, Trust and the Demand for Public Services: Evidence from a Nationwide Family Planning Program”, Working Paper.

Lowes, S and E Montero (2021), "The legacy of colonial medicine in Central Africa." American Economic Review 111(4): 1284-1314.

Martinez-Bravo, M and A Stegmann (2022), "In vaccines we trust? The effects of the CIA’s vaccine ruse on immunization in Pakistan", Journal of the European Economic Association 20(1): 150-186.

Endnotes

1 All these documents were made publicly available because of the open trial against these authorities, accused of human rights violations.