Politics and patronage exacerbate public sector absenteeism, limiting the efficacy of reform measures

The scope and impact of public sector absenteeism

Public sector absenteeism poses a significant challenge in many developing countries, impacting the delivery of essential services such as education and healthcare (Banerjee et al. 2004, Kremer et al. 2005, World Health Organisation 2022). The problem is substantial and persistent: in the early 2000s, one in three educators and one in five health workers were absent from their jobs across Bangladesh, Ecuador, India, Indonesia, Peru, and Uganda (Chaudhury et al. 2006); more recently, 30% of all health workers were absent across 10 African countries (Laura et al. 2020).

Studies have shown that absenteeism among public sector workers can have negative consequences for service delivery and outcomes. For example, research in India found that reducing teacher absence can significantly improve student achievement (Duflo et al. 2012). In rural India, investing in reducing teacher absence was found to be more cost-effective than hiring additional teachers (Muralidharan et al. 2016). At the same time, efforts to address this issue through monitoring and incentives have yielded mixed results (Banerjee and Duflo 2006, Banerjee et al. 2008, Olken and Pande 2012, Dhaliwal and Hanna 2017, Finan et al. 2017, Callen et al. 2020a, Muralidharan et al. 2021). In our research, we set out to investigate why monitoring reforms yield mixed results.

Absenteeism in the healthcare sector in Punjab, Pakistan

In November 2011 we conducted surprise, independent inspections of a representative sample of 850 of Punjab’s near 2500 provincial rural health clinics (dubbed Basic Health Units (BHUs)). We found that government doctors posted to BHUs were absent from their facility during open hours two-thirds of the time (Callen et al. 2023). This is particularly alarming as BHUs provide primary care for nearly all of Punjab’s rural population, including outpatient care, pre- and postnatal care and deliveries, and vaccinations.

Given these alarming doctor absence rates, we partnered with the Punjab government and the World Bank to design, implement, and experimentally evaluate a smartphone monitoring reform. The reform compelled hospital inspectors to carry smartphones that geocode and time-stamp inspections on a dashboard visible to senior managers, thereby sharpening incentives for health inspectors to monitor clinics and to report data accurately. Like others, we found mixed success of this reform in decreasing doctor absenteeism (Callen et al. 2020).

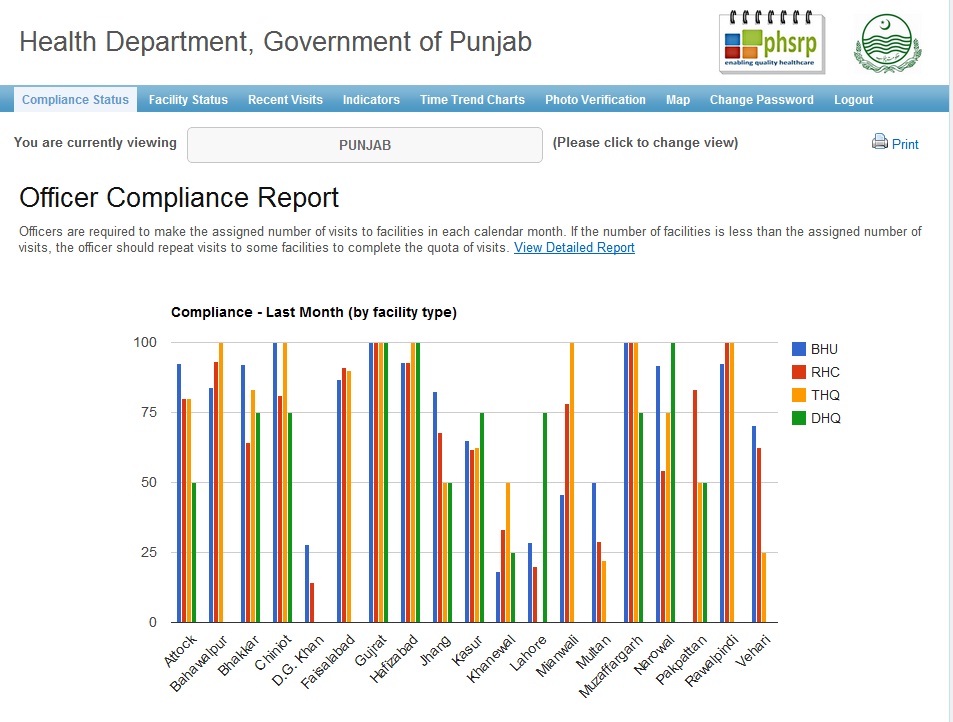

Figure 1: Tracking absenteeism

Note: Online dashboard screenshots.

The role of politics in absenteeism

This study examines how politics intervenes to limit the success of programmes tackling public worker absenteeism. We embedded data collection on the role of local politics in the design of our at-scale smartphone monitoring evaluation. From the outset, we meticulously developed our evaluation methodology to gather data and operate on a large scale, enabling us to gain insights into how local politics impacts absenteeism and the potential for reform. Our evaluation encompassed the entire province of Punjab in Pakistan, with a population of over 100 million people, spanning 297 electoral constituencies. This extensive coverage allowed us to capture a diverse range of local political dynamics prevalent in the region and assess the role of politics in the effectiveness of bureaucratic reforms, with a focus on the links between patronage jobs and absenteeism.

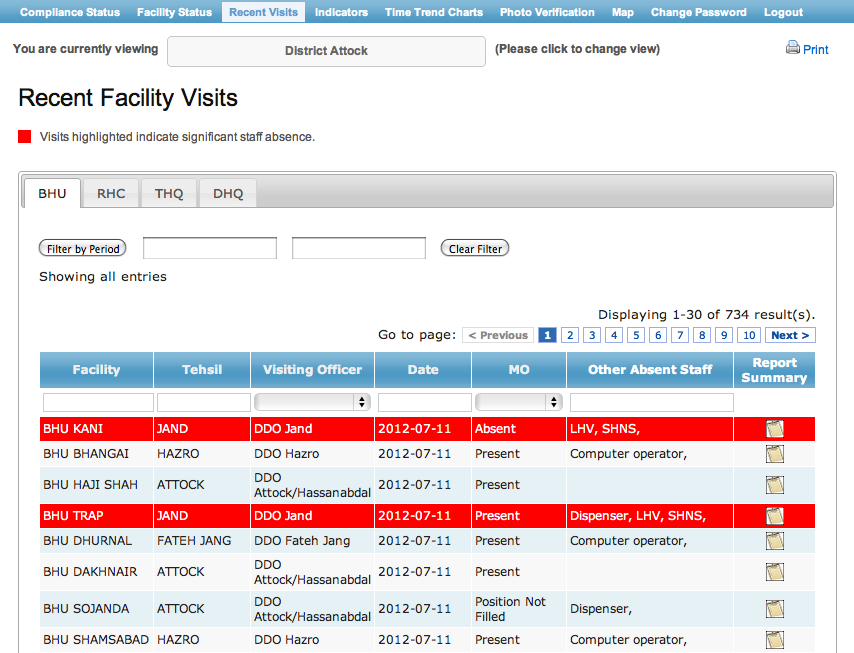

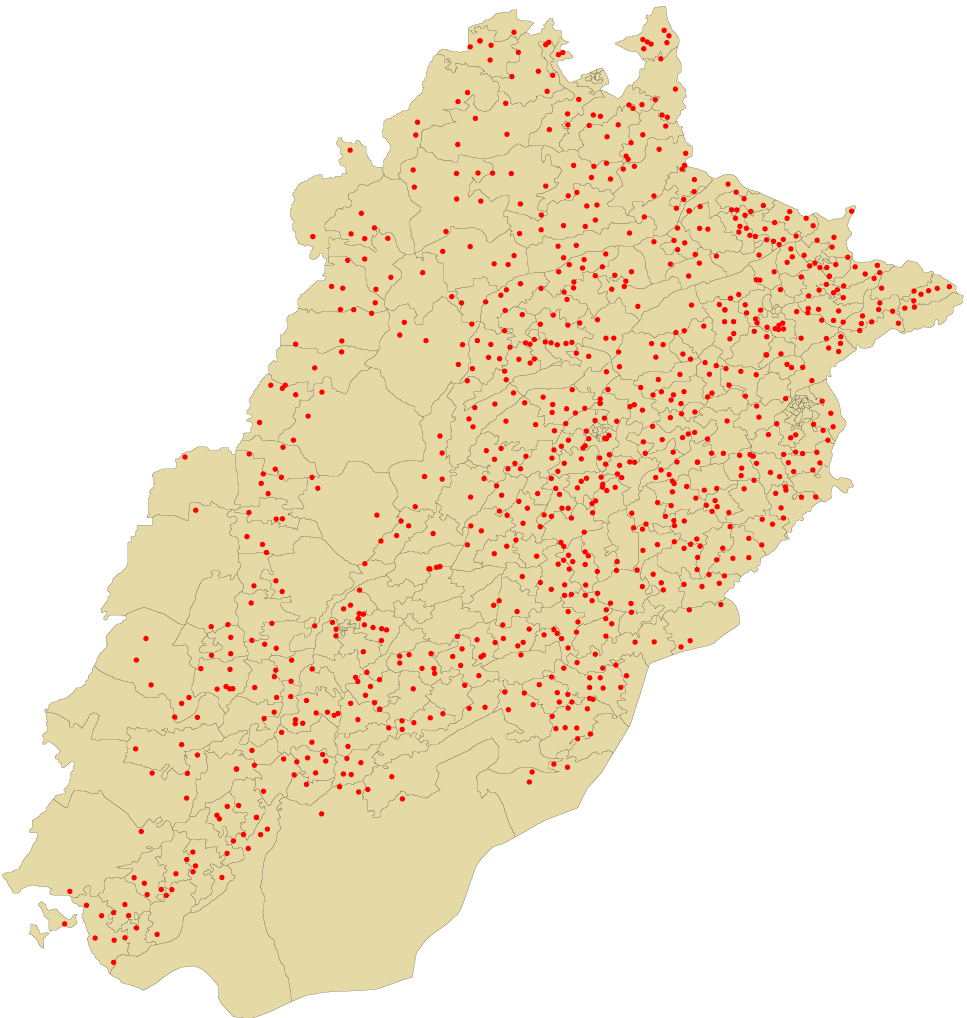

Figure 2: Experimental sample and 2008 political outcomes by constituency

Notes: Drawn borders demarcate Provincial Assembly constituencies in Punjab. The Herfindahl index in Panel B is computed as the sum of squared candidate vote shares in each provincial assembly constituency during 2008 elections.

Our analysis uncovers several key insights into the political dimensions of absenteeism

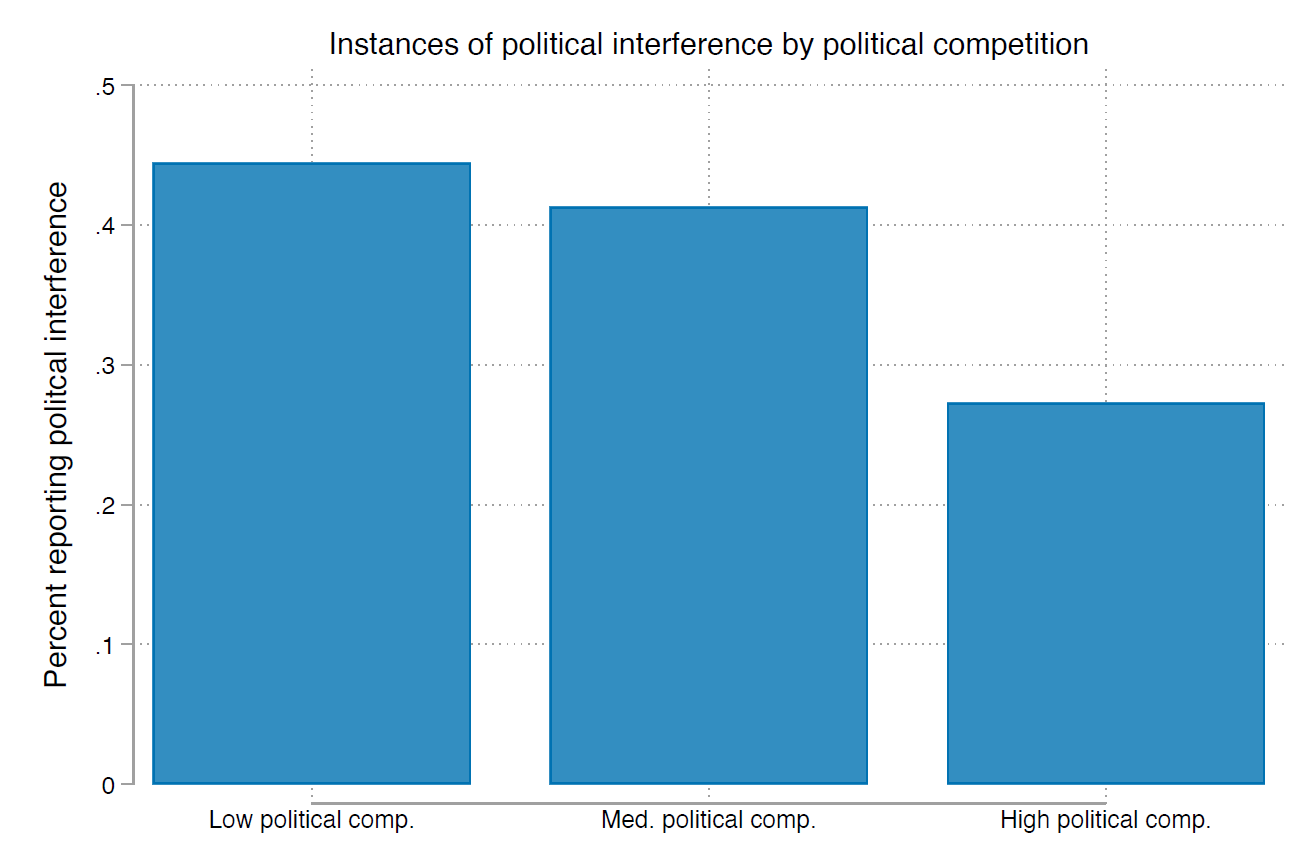

Interviews with health officials revealed that politicians often interfere in decisions related to sanctioning underperforming employees. Approximately 40% of officials reported instances of politicians protecting doctors from accountability. Notably, interference was more prevalent in less competitive electoral constituencies, indicating a link between political dynamics and absenteeism.

Figure 3: Instances of political interference by political competition

Note: Data come from a survey of the universe of senior health bureaucrats and inspectors in Punjab, 149 individuals. Political interference is whether the bureaucrat was influenced by any powerful actor to either (a) not take action against doctors or other staff who were performing unsatisfactorily in their jurisdiction (county) or (b) assign doctors to their preferred posting in the previous two years. Political competition is measured using a party Herfindahl index, or the sum of squared candidate vote shares in each provincial assembly constituency during 2008 elections. High, medium, and low correspond to first, second, and third terciles of competitiveness.

Using a geographic regression discontinuity design, we found that lower political competition in constituencies was associated with lower doctor attendance rates. Doctors connected to local politicians were significantly more likely to be absent during random audits. Furthermore, doctors affiliated with politicians in political strongholds were even more likely to be absent.

The impact of monitoring reforms in this context

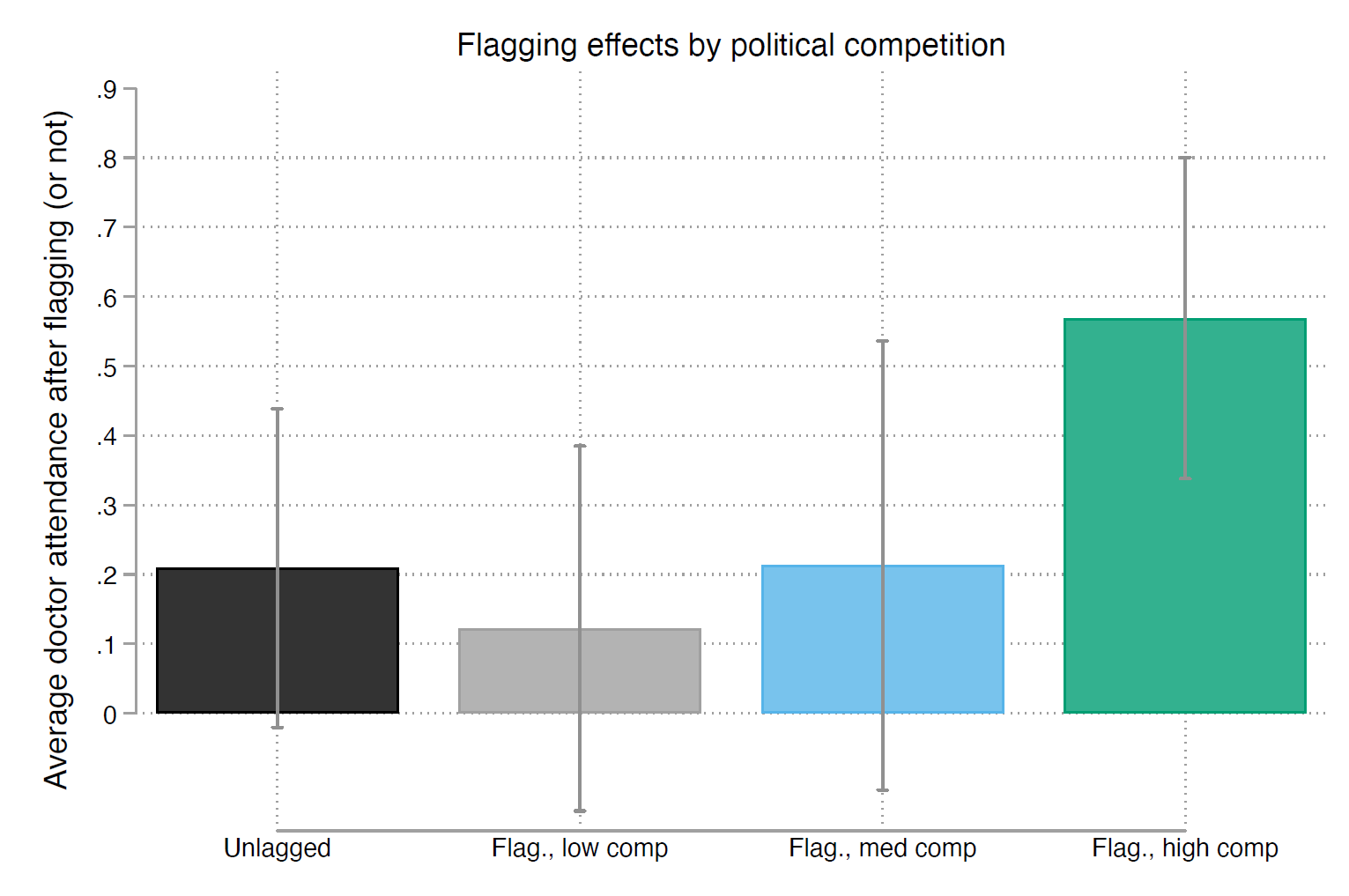

Our evaluation of a smartphone monitoring reform revealed mixed success in reducing absenteeism. However, in politically competitive constituencies, increased monitoring led to a modest improvement in doctor attendance, and doctors without political connections showed a more significant increase in attendance.

Furthermore, manipulating the salience of doctor attendance records on a web dashboard where data are summarised and presented to senior officials resulted in a substantial increase in doctor attendance. However, the efficacy of this information salience intervention was constrained by the political environment. Senior bureaucrats could only boost attendance in highly politically competitive areas and for doctors without political connections.

Figure 4: Flagging effects by political competition

Note: Reports average doctor attendance from independent, unannounced visits to clinics based on whether doctor attendance records were made salient through being “flagged” on the web dashboard used by senior policymakers. Clinics were flagged in red on an online dashboard if three or more of the seven staff were absent in one or more health inspections (see Figure 1 above). Flagged clinics are further divided into those in electoral constituencies with low, medium, and high political competition. Political competition is measured using a party Herfindahl index, or the sum of squared candidate vote shares in each provincial assembly constituency during 2008 elections. High, medium, and low correspond to first, second, and third terciles of competitiveness.

Implications and policy recommendations

Our findings highlight the complex nature of the political economy surrounding public sector absenteeism. They suggest several important considerations for interventions aimed at combating absenteeism:

- Professionalising the civil service: Reducing politicians' involvement in bureaucratic decisions related to hiring, firing, promotion, and posting can mitigate the use of public sector positions as patronage. However, implementing such reforms is challenging in practice.

- Leveraging political incentives: Increasing voter awareness of public sector absenteeism can amplify the political costs for politicians who prioritise patronage. Making information on absenteeism publicly available, such as through public-facing portals, can help hold politicians accountable.

- Data and evidence-based policy: While data and evidence play a crucial role in informing policy, political considerations significantly impact the potential for effective implementation. Understanding the interactions between politicians, bureaucrats, and citizens is essential for sustainable policy improvement.

References

Banerjee, A V, A Deaton, and E Duflo (2004), “Wealth, Health, and Health Services in Rural Rajasthan,” American Economic Review, 94(2): 326–330.

Banerjee, A and E Duflo (2006), “Addressing Absence,” The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(1): 117–132.

Banerjee, A V, E Duflo, and R Glennerster (2008), “Putting a Band-Aid on a Corpse: Incentives for Nurses in the Indian Public Health Care System,” Journal of the European Economic Association, 6(2-3): 487–500.

Callen, M, S Gulzar, A Hasanain, M Y Khan, and A Rezaee (2020), “Data and policy decisions: Experimental evidence from Pakistan,” Journal of Development Economics, 146: 102523.

Callen, M, S Gulzar, A Hasanain, M Y Khan, and A Rezaee (2023), "The political economy of public sector absence," Journal of Public Economics, 218: 104787.

Chaudhury, N, J Hammer, M Kremer, K Muralidharan, and F H Rogers (2006), “Missing in Action: Teacher and Health Worker Absence in Developing Countries,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(1).

Dhaliwal, I and R Hanna (2017), “Deal with the Devil: The Successes and Limitations of Bureaucratic Reform in India,” Journal of Development Economics.

Di Giorgio, L, D K Evans, M Lindelow, S N Nguyen, J Svensson, W Wane, and A Welander Tärneberg (2020), “An Analysis of Clinical Knowledge, Absenteeism, and Availability of Resources for Maternal and Child Health,” The British Medical Journal: Global Health, 5(12).

Duflo, E, R Hanna, and S P Ryan (2012), “Incentives work: Getting teachers to come to school,” American Economic Review, 102(4): 1241–1278.

Finan, F, B A Olken, and R Pande (2017), The Personnel Economics of the State, North Holland.

Kremer, M, N Chaudhury, F H Rogers, K Muralidharan, and J Hammer (2005), “Teacher Absence in India: A Snapshot,” Journal of the European Economic Association, 3(2-3): 658–667.

Muralidharan, K, J Das, A Holla, and A Mohpal (2017), “The fiscal cost of weak governance: Evidence from teacher absence in India,” Journal of Public Economics, 145: 116–135.

Muralidharan, K, P Niehaus, S Sukhtankar, and J Weaver (2021), "Improving last-mile service delivery using phone-based monitoring," American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 2: 52-82.

Olken, B A and R Pande (2012), “Corruption in Developing Countries,” Annual Review of Economics, 4: 479–505.

World Health Organization (2022), “Covid-19 Pandemic Fuels Largest Continued Backslide in Vaccinations in Three Decades,” News Release.