Intuitively, trade liberalisation should increase the appeal of left-wing parties that offer to protect workers with protectionist policies. Evidence from Brazil shows how liberalisation actually reduced votes for the left by undermining labour unions, the traditional support base of many left-wing parties.

Editor's note: This article originally appeared on VoxEU.

The political consequences of trade exposure and of trade liberalisation have become a fiercely debated topic, especially after Brexit, the ongoing trade war between the US and China, and the spread of anti-globalisation sentiment worldwide. Indeed, in different contexts, recent research in economics and political science has linked trade shocks to reduced incumbent advantage, to gains for parties identified with protectionist policies, and to political radicalisation (e.g. Autor et al. 2020, Blanchard et al. 2019, Choi et al. 2021, Colantone and Stanig 2017, Dippel et al. 2021). These responses are typically interpreted as driven by individual-level reactions, motivated either by economic or identitarian concerns.

In our recent study (Ogeda et al. 2024), we examine the consequences of Brazil’s trade liberalisation in the first half of the 1990s. In doing so we corroborate some of the findings of this literature: the trade shock had significant, and permanent, electoral consequences. However, our results do not fit the pattern of reactions highlighted in previous research. Instead, we uncover the role of a novel institutional channel as a vehicle for the effects of trade shocks on political outcomes: labour union strength.

Trade liberalisation reduced votes for the left

We find that, in the regions more affected by the tariff cuts of the early 1990s, there was a significant decrease in votes for the left in all subsequent presidential elections, relative to the regions less affected by the tariff cuts. We consider the impact on each of the 485 microregions of Brazil, defining a region-specific tariff cut based on the pre-shock industry composition of employment.

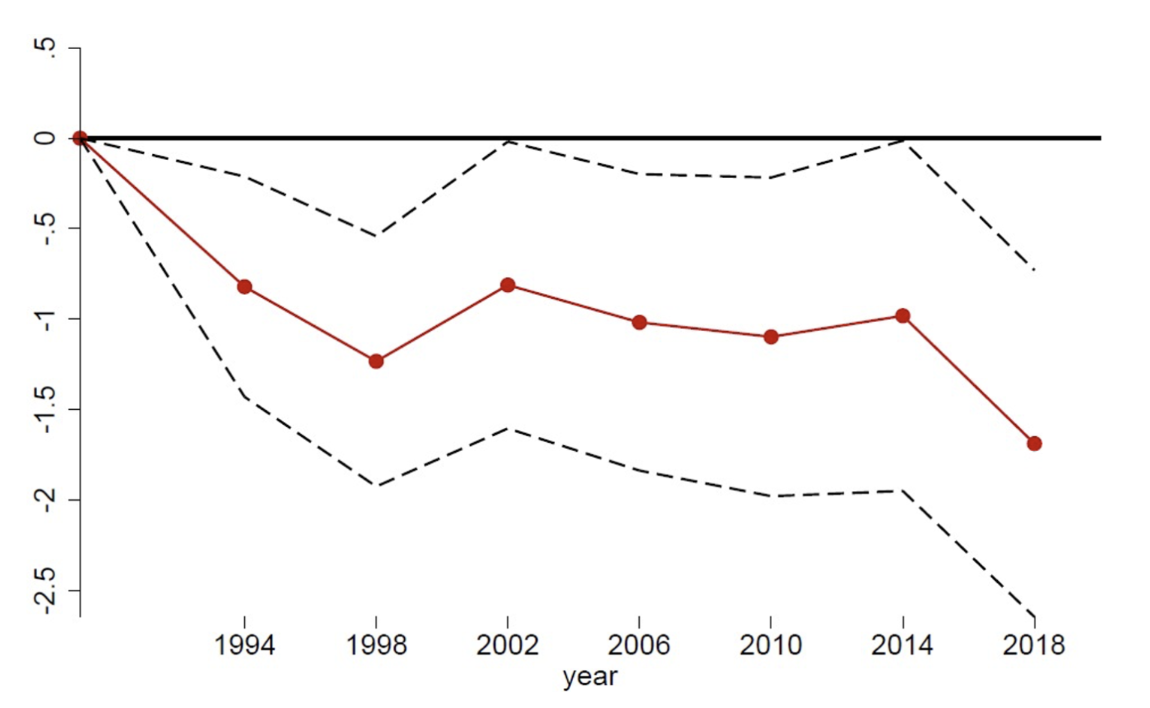

Figure 1 shows the estimates (with 95% confidence intervals) for the impact of the tariff cuts on the vote share of the left in the first round of elections from 1994 to 2018. The effect is consistently negative, statistically significant, and stable over time, indicating a permanent effect lasting at least 25 years. The magnitude of the relationship is sizable. For example, a one standard-deviation increase in the tariff reduction induces a reduction of 4 percentage points in the share of votes for left-wing candidates in the first round of the presidential elections after the liberalisation, when compared to the 1989 election, which happened just before the shock. If we consider the runoff elections, the magnitude of the effect is larger.

This result may seem puzzling at first. Since the policy was implemented by a right-wing party, and since we know from previous research (Kovak 2013, Dix-Carneiro and Kovak 2017) that the more affected areas also suffered a deterioration in labour market conditions, this is the opposite of what individual-level reactions (e.g. punishing those aligned with the party that implemented the reform, or replacing them with more protectionist politicians) would suggest. The explanation should therefore be of a different nature.

Figure 1 Impact of the tariff cuts on the vote share of left-wing candidates

Notes: Each dot represents the estimated coefficient of a regression of the difference in vote share for the left in an election relative to the 1989 pre-shock election on the microregion-specific tariff cut. Negative estimates imply fewer votes for left-wing candidates in regions facing larger tariff reductions. Dashed lines show 95% confidence intervals.

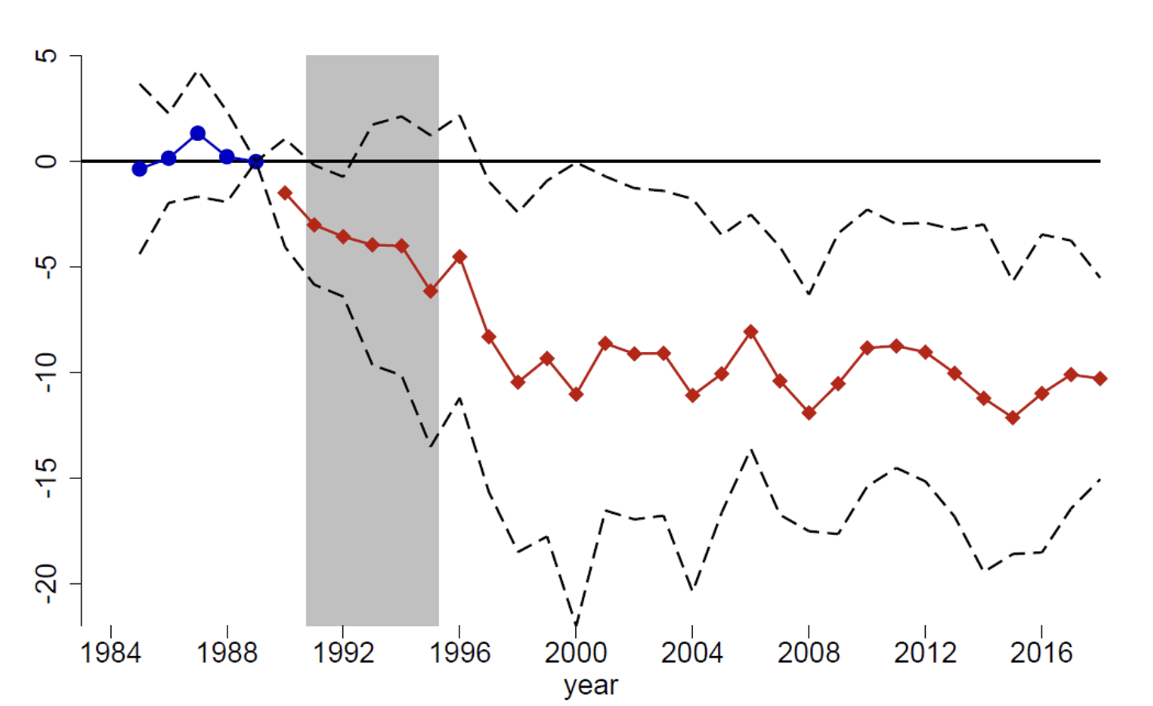

Trade liberalisation weakened labour unions

We show that labour unions are likely an important vehicle for this effect. In particular, we find that union presence (measured in different ways) decreased in the areas more affected by the tariff cuts, relative to the national average. Figure 2 shows the results for one of those measures of union presence: the number of workers employed by unions, relative to the population of the microregion. The figure shows that the effect of the tariff cuts on unions’ workforce is negative in every year after 1989. During the transition years of 1991-1995 (in gray), the estimates are not statistically different from zero, but since 1997 they become stable and statistically different from zero at the 5% level until the end of the sample period. Hence, labour unions’ workforce fell in regions that faced deeper tariff cuts, relative to regions facing smaller tariff reductions. Once again, the effect is stable and long-lasting.

Could these effects simply represent a trend already present before the shock? In a ‘placebo’ test where we consider the differences in the number of union employees per capita for years prior to the shock, relative to 1989 (the blue circles in Figure 2), we do not find any evidence of that.

The political science literature (e.g. Kim and Margalit 2017) has pointed out several channels through which unions affect electoral outcomes, from turnout mobilisation to shaping workers’ political views to campaign contributions. Thus, their weakening can help to explain changing voting patterns due to the trade reform. This channel is particularly plausible in Brazil for at least two reasons. First, until 2017 labour unions relied financially on a compulsory fee charged to every worker whose activity was represented by a union. But this covered only formal workers, and previous research (Ponczek and Ulyssea 2021) has shown that the tariff cuts decreased formality in the most affected areas. Second, as in most countries, in Brazil labour unions and left-wing parties are historically connected. In fact, as Colistete (2007) points out, most of the main left-wing parties were founded by former union leaders. Thus, labour unions in harder-hit regions could have lost their financial and organisational capacity to influence elections in favour of their preferred candidates, who are typically from the left.

Figure 2 Impact of the tariff cuts on labour unions’ employment

Notes: Each dot represents the estimated coefficient of a median regression of the difference in the number of union employees per thousand people between 15 and 65 years old relative to the 1989 pre-shock level on the microregion-specific tariff cut. Red diamonds indicate post-1989 estimates; blue circles indicate pre-1989 estimates. Negative estimates imply fewer union employees in regions facing larger tariff reductions. Dashed lines show 95% confidence intervals. The shaded area indicates that the liberalisation process began in 1991 and ended in 1995.

Indeed, we confirm that the relationship between tariff cuts and votes for the left is driven exclusively by candidates from political parties linked to unions. These parties are often, but not always, from the left. Similarly, while many parties from the left have ties to unions, not all of them do. We find that the tariff cuts increase the vote share of leftist parties without links to unions, so the overall reduction of votes for the left is due solely to the dwindling support for the parties with ties to unions. These findings corroborate the hypothesis that the liberalisation reduced the vote share of the left in the most affected regions through the weakening of labour unions.

Conclusion

Economic shocks can have consequences that go far beyond purely economic outcomes. Large programmes of trade liberalisation are no exception. We find that the significant reduction of trade barriers in Brazil in the early 1990s eroded the support for left-wing candidates in all subsequent elections in the regions more affected by the shock, relative to the average of the country. Unlike much of the current literature linking trade shocks to electoral outcomes, in the Brazilian context the political consequences of the trade reform are not driven by individual-led reactions. Instead, an important mechanism has been the weakening of labour unions in the regions more affected by the tariff cuts, which undermined their capacity to offer political support for parties on the left. This institutional channel helps to explain the long-term impacts of the reform.

A final caveat is in order. Our empirical approach is only able to identify relative effects, comparing regions more and less affected by the tariff cuts. Therefore, we cannot say anything about the overall effect of the trade reform on electoral outcomes and on union strength.

References

Autor, D, D Dorn, G Hanson and K Majlesi (2020), “Importing Political Polarization? The Electoral Consequences of Rising Trade Exposure”, American Economic Review 110(10): 3139-83.

Blanchard, E J, C P Bown and D Chor, D (2019), “Trump’s trade war cost Republicans congressional seats in the 2018 midterm elections”, VoxEU.org, 26 November.

Choi, J, I Kuziemko, E L Washington and G Wright (2021), “Local Employment and Political Effects of Trade Deals: Evidence from NAFTA”, Mimeo.

Cantalone, I and P Stanig, P (2017), “Globalisation and economic nationalism”, VoxEU.org, 20 February.

Colistete, R P (2007), “Productivity, Wages, and Labor Politics in Brazil, 1945-1962”, The Journal of Economic History 67(1): 93-127.

Dippel, C, R Gold, S Heblich and R Pinto (2021), “The Effect of Trade on Workers and Voters”, Economic Journal 132(641): 199-217.

Dix-Carneiro, R and B K Kovak (2017), “Margins of labour market adjustment to trade”, VoxEU.org, 23 August.

Kim, S E and Y Margalit (2017), “Informed Preferences? The Impact of Unions on Workers' Policy Views”, American Journal of Political Science 61(3): 728-743.

Kovak, B K (2013), “Regional Effects of Trade Reform: What is the Correct Measure of Liberalization?” American Economic Review 103(5): 1960-76.

Ogeda, P, E Ornelas and R Soares (2024), “Labor Unions and the Electoral Consequences of Trade Liberalization”, Journal of the European Economic Association, forthcoming.

Ponczek, V and G Ulyssea (2021), “Enforcement of Labor Regulations and the Labor Market Effects of Trade: Evidence from Brazil”, The Economic Journal 132(641): 361-390.