Does discrimination based on gender identity or sexual orientation during the housing search add to existing forms of discrimination and marginalisation? Does this further limit the opportunities for LGBTQ+ people in Latin America?

Many individuals within the LGBTQ+ community - encompassing lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and other diverse sexual orientations and gender identities - face widespread discrimination, exclusion, and violence. Despite increasing efforts to provide equal rights and opportunities, they are still often marginalised based on their gender identity and sexual orientation, restricting their access to opportunities and resulting in lower educational attainment, higher unemployment rates, and insufficient access to adequate services (Badgett et al. 2021).

One key determinant of individuals’ living conditions and opportunities is access to decent, safe, and affordable housing (Bergman et al. 2019, Chetty and Hendren 2018, Chetty et al. 2016, Chyn 2018). Although highly relevant, evidence on discrimination against LGBTQ+ individuals in the housing market is limited to a handful of countries in Europe and North America (see, for instance, Ahmed and Hammarstedt 2008, Ahuja and Lyons 2019, Gouveia et al. 2020, Hellyer 2021, Koehler et al. 2018, Lauster and Easterbrook 2011, Levy et al. 2017, Murchie and Pang 2018).

What challenges do LGBTQ+ individuals face in the rental housing market in less developed - and probably more conservative - regions?

In joint research with Nicolás Abbate, Joaquín Coleff, Luis Laguingue, Margarita Machelett, and Julián Pedrazzi (Abbate et al. 2024), we assess the extent of discrimination against LGBTQ+ people when searching for an apartment to rent in Latin America. To this end, we conducted a large-scale correspondence study in the largest cities of Argentina, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru.

In our experiment, fictitious couples submitted inquiries to property managers through

a major online rental housing platform expressing their interest in renting an advertised property and requesting a visit. These messages were identical, except for one detail: some of these fictitious couples signalled to be cisgender heterosexual, others to be cisgender male gay, and others to be transgender heterosexual couples—i.e. a heterosexual couple where the female partner is a transgender woman. Thus, by randomly varying the type of couple, we can identify discriminatory behaviour based on the renter’s perceived gender identity or sexual orientation.

Subsequently, we analysed the outcomes of these interactions. We recorded whether there was a response to the inquiry or not, and we noted the type of response—whether it was positive (indicating the property’s availability) or not, and whether there was an invitation to visit the property or not.

Trans couples are discriminated against in the rental market

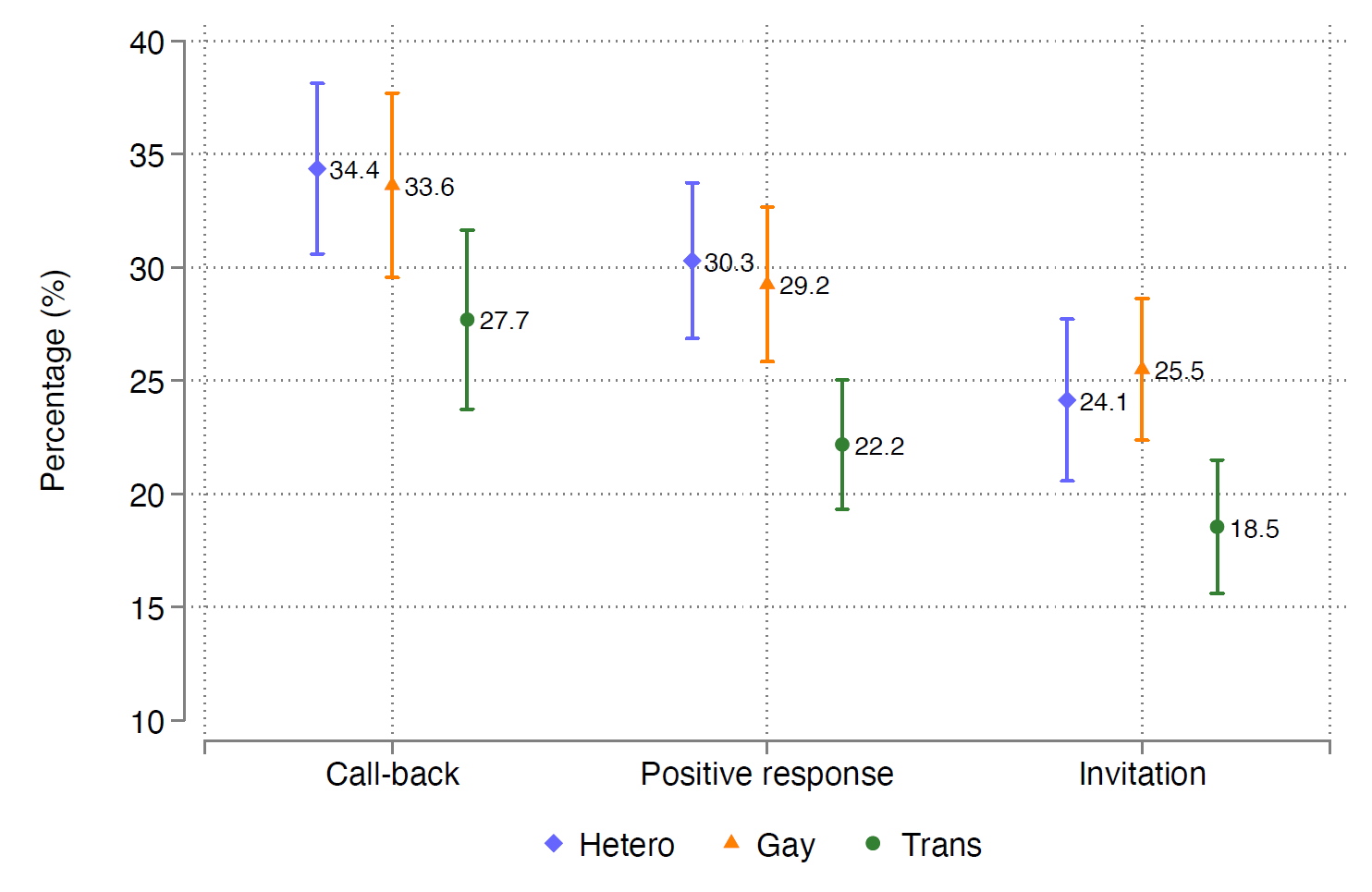

The most striking and worrisome result of our study is that trans couples received 19% fewer responses, 27% fewer positive responses, and 23% fewer invitations to visit the property compared to hetero-cis or male gay couples (see Figure 1). Interestingly, we find no evidence of discrimination for gay male couples.

Figure 1: Average call-back, positive response, and invitation rates

Note: The figure shows the call-back, positive response, and invitation rates with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals for the three types of couples when no employment information is disclosed. For heterosexual couples, the average call-back rate is 34.4%, and the positive-response rate is 30.3%. Gay- male couples receive fewer responses and positive responses: 33.6% and 29.3%, respectively, although the gap relative to heterosexual couples is not statistically significant. In contrast, neutral trans couples receive significantly fewer responses than heterosexual or gay couples: their call-back rate is 27.7% and their positive-response rate is only 22.2%.

Does taste-based or statistical discrimination explain why trans couples received fewer responses and invitations?

We also study whether this discriminatory behaviour against trans couples reflects taste-based discrimination or statistical discrimination - i.e. whether property managers discriminate based on other characteristics commonly associated with transgender individuals beyond their gender identity. For instance, if landlords believe that trans people are less likely to have a stable job and to pay the rent on time, they might prefer having heterosexual cisgender couples as tenants, even without knowing the true financial situation of the trans couple inquiring (statistical discrimination).

We test this by randomly varying the amount of information disclosed in the message sent to property managers about the tenants’ employment and financial capacity. We split each of the three couple groups (cisgender heterosexual, cisgender male gay or transgender heterosexual) into two groups where one group provides no information (neutral group) and the other discloses a strong labour market signal (quality-job group). We then compare call-back rates, positive response rates, and invitation rates for the same type of couple, but with different signals. If statistical discrimination is prevalent, then the disclosure of the strong labour market signal should reduce the observed gaps.

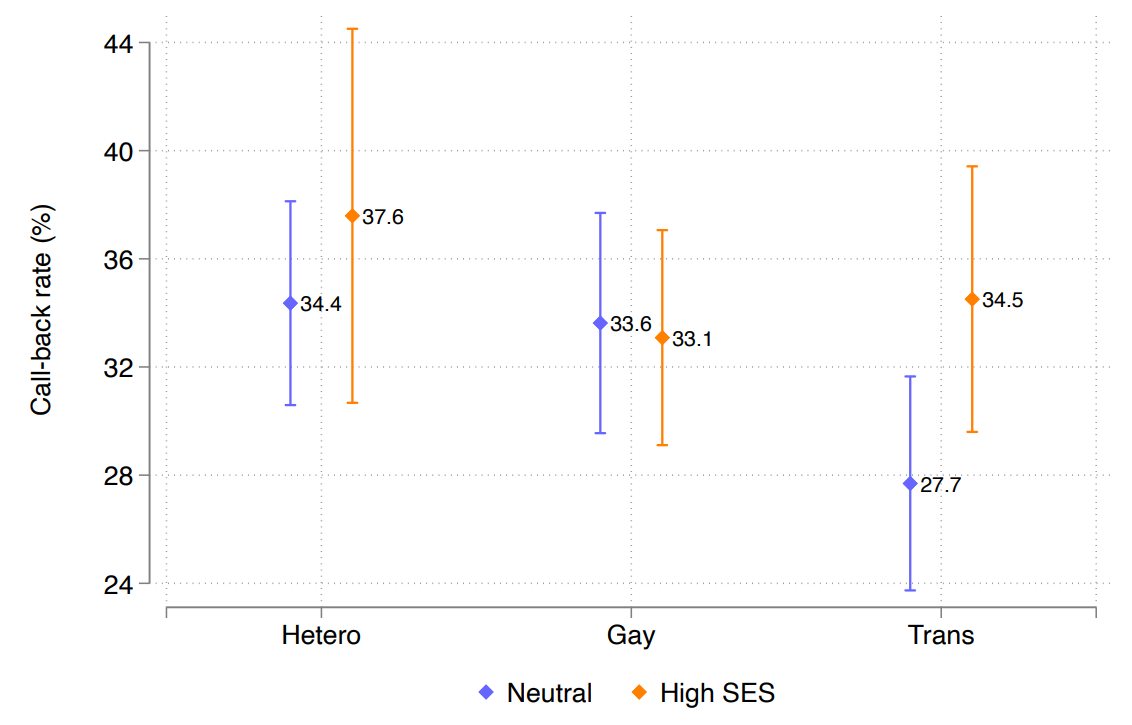

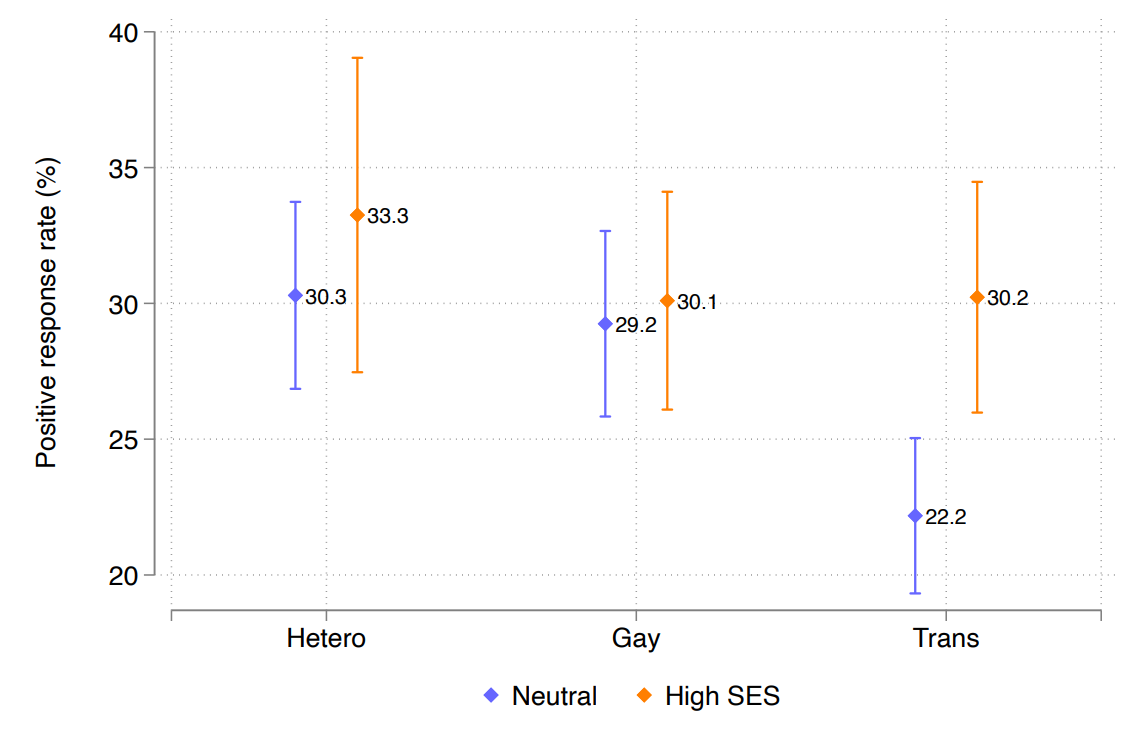

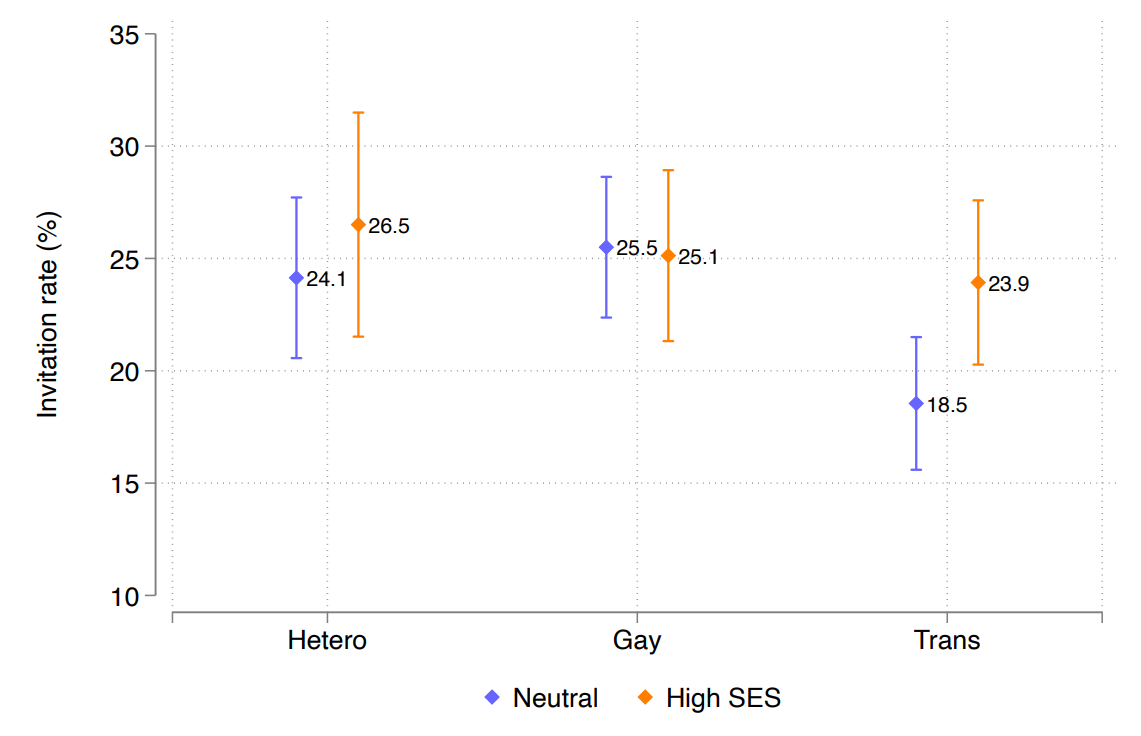

We find that discriminatory treatment against trans couples decreases when they indicate they have a good and stable job suggesting the presence of statistical discrimination against trans couples. Importantly, we find no statistically significant effect of disclosing the quality-job signal on any outcome for heterosexual or gay male couples (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Average call-back rates (LHS), average positive-response rates (RHS), and average invitation rates for neutral and quality-job couples (centre)

Note: The figure shows average call-back rates (left panel), positive response rates (right panel), and invitation rates (centre panel) with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals for each type of couple with and without the quality-job signal. Figure 2c shows large and statistically significant differences when trans couples provide the quality-job signal: their call-back rates, positive-response rates, and invitation rates increase respectively by 7, 8, and 5 percentage points, implying differentials of 25%, 36%, and 29% relative to neutral trans couples. These results suggest the presence of statistical discrimination against trans couples.

Our findings also reveal that discrimination against transgender couples intensifies in specific contexts. Property managers exhibit greater discrimination when dealing with newer listings or low-priced properties, indicating that trans couples may be restricted from accessing the best rental opportunities.

A few limitations and policy implications for reducing discrimination against LGBTQ+ people

We only look at the initial stage of the housing search and so do not know how the interaction continues. Our research therefore cannot capture whether more discriminatory events occur throughout the rental process both for trans couples and gay couples.

However, our study yields important lessons for the design of effective public policies that reduce the barriers faced by LGBTQ+ people at this initial stage of the housing search process. We find that strong discrimination exists against trans couples compared to gay male and heterosexual couples, but we also find that the discriminatory treatment decreases significantly when trans couples disclose that they have a stable job and rental collateral. Therefore, policies that improve job security for trans people such as employment quotas or programmes facilitating access to rental guarantees, as well as campaigns that change the perceived labour market and financial capacity of LGBTQ+ members can reduce discriminatory treatment.

Editors' note: This column is published in collaboration with the International Economic Associations’ Women in Leadership in Economics initiative which aims to enhance the role of women in economics through research, building partnerships, and amplifying voices.

References

Abbate, N, I Berniell, J Coleff, L Laguinge, M Machelett, M Marchionni, J Pedrazzi, and M F Pinto (2024), “Discrimination against gay and transgender people in Latin America: A correspondence study in the rental housing market,” Labour Economics, 87: 102486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2023.102486.

Ahmed, A M, and M Hammarstedt (2008), “Discrimination in the rental housing market: A field experiment on the Internet,” Journal of Urban Economics, 64(2): 362–372.

Ahuja, R, and R C Lyons (2019), “The silent treatment: Discrimination against same-sex relations in the sharing economy,” Oxford Economic Papers, 71: 564–576.

Badgett, M V L, C S Carpenter, and D Sansone (2021), “LGBTQ economics,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 35: 141–170.

Bergman, P, R Chetty, S DeLuca, N Hendren, L F Katz, and C Palmer (2019), “Creating moves to opportunity: Experimental evidence on barriers to neighborhood choice,” Technical report, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Chetty, R, and N Hendren (2018), “The impacts of neighborhoods on intergenerational mobility II: County-level estimates,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 133(3): 1163–1228.

Chetty, R, N Hendren, and L F Katz (2016), “The effects of exposure to better neighborhoods on children: New evidence from the Moving to Opportunity experiment,” American Economic Review, 106(4): 855–902.

Chyn, E (2018), “Moved to opportunity: The long-run effects of public housing demolition on children,” American Economic Review, 108(10): 3028–56.

Gouveia, F, T Nilsson, and N Berggren (2020), “Religiosity and discrimination against same-sex couples: The case of Portugal’s rental market,” Journal of Housing Economics, 50(C).

Hellyer, J (2021), “Homophobia and the home search: Rental market discrimination against same-sex couples in rural and urban housing markets,” Journal of Housing Economics, 51: 101744.

Koehler, D, G Harley, and N Menzies (2018), “Discrimination against sexual minorities in education and housing: Evidence from two field experiments in Serbia,” Policy Research Working Paper Series 8504, The World Bank.

Lauster, N, and A Easterbrook (2011), “No room for new families? A field experiment measuring rental discrimination against same-sex couples and single parents,” Social Problems, 58: 389–409.

Levy, D K, D Wissoker, and C L A B (2017), “A paired-testing pilot study of housing discrimination against same-sex couples and transgender individuals,” Urban Institute Research Report.

Murchie, J, and J Pang (2018), “Rental housing discrimination across protected classes: Evidence from a randomized experiment,” Regional Science and Urban Economics, 73: 170–179.