When hosting refugees, increased humanitarian aid coupled with inclusive hosting policies can create a mutually beneficial environment for both host and refugee communities

Background

There are currently 80 million forcibly displaced persons in the world, and that number is only growing. It has become critical to explore the effects of refugee presence on their respective communities with the rapid influx of asylum seekers and displaced populations. The presence of migrants also generates a host of consequences both economically and socially. In high- and upper-middle-income countries (HMICs), many refugees have faced hostile responses and unfavourable attitudes towards their integration, and migrant groups are often targeted for hate crimes (Dancygier et al. 2020).

Because these dynamics are largely explored only in HMICs, we wanted to examine the effects of refugee presence in low-income countries, where the vast majority of people experiencing displacement reside. Important factors in lower-income countries that may offset anti-refugee backlash are missing in HMICs. Notably, in lower-income countries, an increase in international humanitarian aid to support refugee resettlement could positively spill over into local communities.

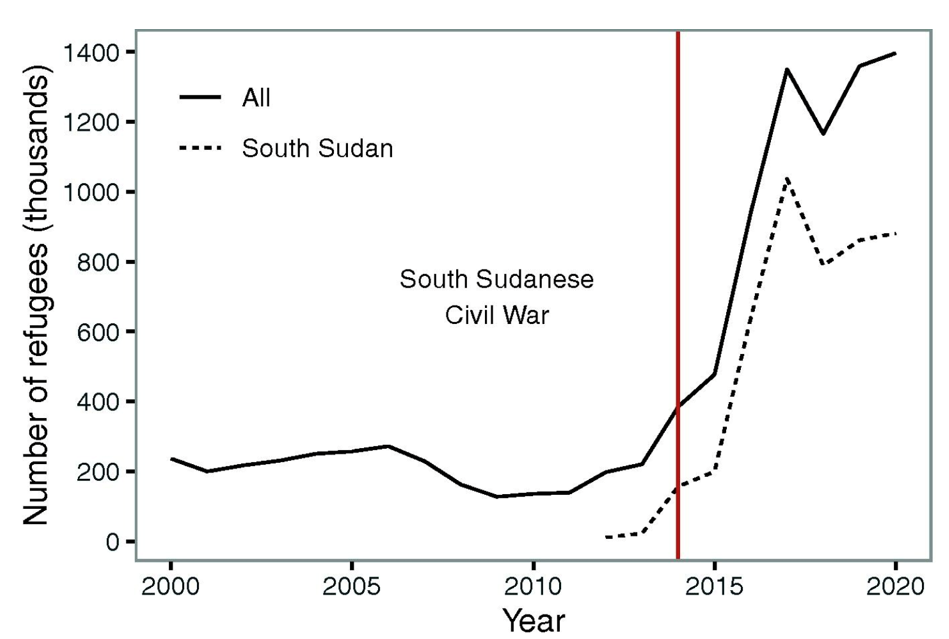

We chose Uganda as the primary setting for our study (Zhou, Grossman, and Ge 2023) for several reasons. Due to the conflict in South Sudan starting in 2014, Uganda now hosts 1.5 million refugees (see Figure 1), one of the largest refugee populations in the world. Unlike many host countries who segregate refugees in camps, Uganda has adopted inclusive hosting policies such as allowing refugees to live in open settlements not fenced-in camps, and provides refugees access to important public services (UNHCR 2020, Ronald 2022). Major policies like the 2006 National Refugee Act, the 2010 Refugee Regulations, and the Development Response to Displacement Impacts Project (DRDIP) have allowed refugees to obtain critical rights (e.g. freedom of movement, and right to work) while also ensuring that host communities have access to some of the aid. These unique characteristics make Uganda a leading actor of inclusivity and accessibility for refugees.

Figure 1: Increase in number of refugees hosted in Uganda

Thus, we wondered: do refugees in low-income countries experience backlash (as extensively documented in HMICs)? Using the case of Uganda, we hypothesised that they would not. Context matters, and how the host country frames refugee resettlement through policies and distribution of aid influences host reception.

The process

To bring data to this question, we worked closely with UNHCR Uganda, the World Bank, and various Ugandan ministries. Our analysis is at the parish level, which is a very granular level since there are over 5,000 parishes and each parish encompasses about five villages. Our study covers five time periods (2001, 2006, 2011, 2016, and 2020), which was useful in comparing the much larger numbers of refugees in 2016 and 2020 to the previous years.

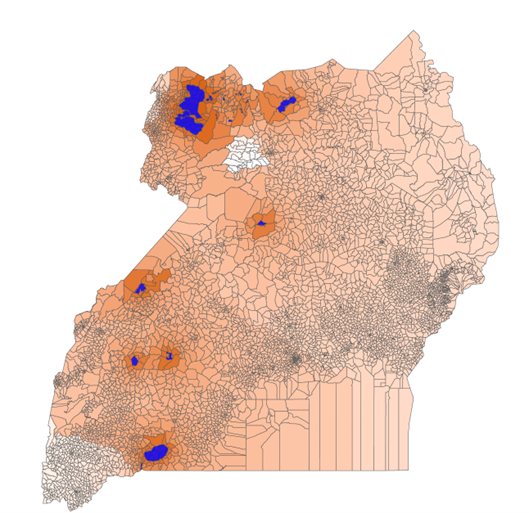

From the UNHCR, we were able to obtain data on where refugees have settled, how many refugees are in each settlement, and the geographic boundaries for those settlements. From there, we created our independent variable – the presence of refugees. Refugee presence is a measure of each parish-year’s proximity to nearby refugee settlements and how large those nearby settlements are. Figure 2 shows a heatmap of the variation in this variable across parishes in 2020, along with where the refugee settlements are.

Figure 2: Map of Uganda’s refugee settlements (blue) and parishes shaded by their level of refugee presence (orange) in 2020

From other sources like Ugandan ministries and the World Bank, we collected data for our main outcomes of interest on public services. This included the locations of over 25,000 primary and secondary schools, 7,000 health clinics, household survey data on usage of health services, and road networks. Finally, to understand Ugandan citizens’ attitudes towards migration, migration policy, and other concerns like fear of crime, we incorporated the nationally representative Afrobarometer surveys.

Having all of this data allowed us to compare these outcomes across parishes over time as a function of their levels of refugee presence.

The effects of refugee presence

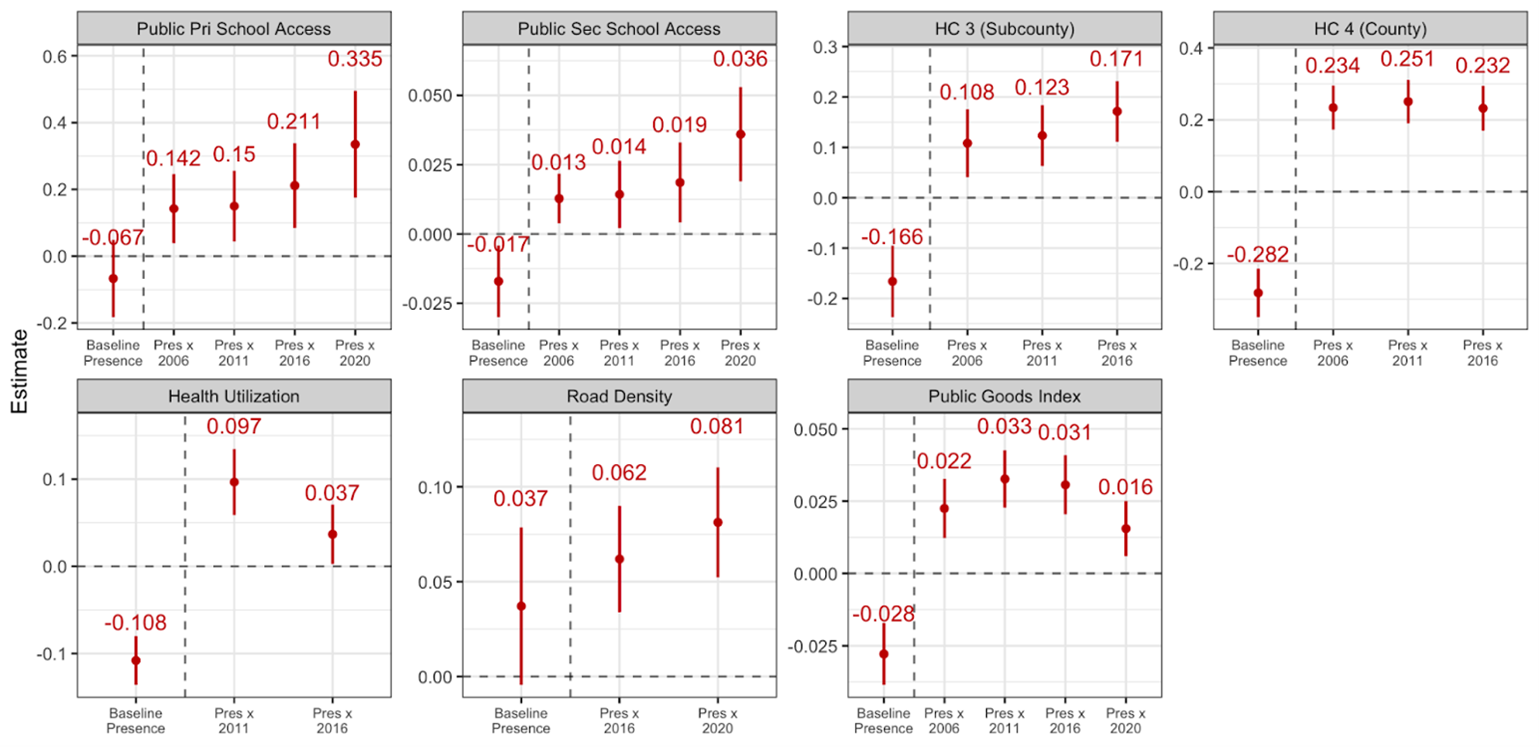

Figure 3: Effect of refugee presence on local public goods

Note: The first estimate shows the relationship between refugee presence and the public service outcome in the baseline year. Subsequent estimates after the dashed line show changes in that relationship.

Each of the plots in Figure 2 first show the relationship between refugee presence and the outcome at the baseline year of 2001, and then each subsequent effect after the dashed line is the change in that effect in the subsequent years. Crucially, we find that parishes with greater levels of refugee presence (especially after policy reforms) have substantially greater access to social services. This is particularly important because we can see that in the year of 2001 (our baseline year), parishes located near large refugee settlements tended to be underserved compared to other places in the country.

In noting these patterns, we find that the largest effects are after 2014, which is when Uganda experienced a massive arrival of South Sudanese refugees, accompanied by an increase in humanitarian aid.

Overall, there are multiple positive and statistically significant effects of refugee presence on public services, allowing the parishes—and thereby host communities—to benefit in mutual aid.

Lack of backlash to refugee presence

Additionally, we find that even with the increase in refugee presence, public opinion and insecurity generally remains the same or negligibly different. This means that refugee integration did not generate as intense or visceral a backlash as we might expect in HMICs.

Specifically, we find that Ugandans who live near large refugee settlements share similar attitudes toward refugees as compared with Ugandans who live further away as measured by questions such as ease of having refugees as neighbours or expressed support for refugee’s freedom of movement as well as their path to citizenship.

We conclude that it is of utmost importance to improve basic services in host communities so that the benefits may be enjoyed by all, which is important for facilitating a non-contentious environment for both hosts and refugees.

Implications and an uncertain future

Through the increase in humanitarian aid for refugees coupled with inclusive hosting policies, we find that there were positive spillovers into Ugandan communities across a multitude of public services, from better access to education and healthcare to more roads. There are several lessons that we can draw based on the experience of host communities in Uganda that can apply broadly:

- Further research on the impact of refugees’ presence on welfare. Most studies on the effects of refugees and other migrants only focus on a single sector, such as the labour market. We analysed multiple sectors – education, health, and infrastructure – but there are additional outcomes left to be examined, like housing markets or food security. Through further research, we can determine exactly what refugee presence means for host communities through various policy domains and outline how government and aid organisations can directly contribute.

- Support the needs of local host communities alongside refugees through humanitarian aid. This two-pronged approach is recommended by UNHCR’s 2018 Global Compact on Refugees. By providing humanitarian aid and public services to the host communities as well, it eases financial pressures and strains on local social services, which also means friendlier and more cohesive attitudes towards refugees.

- Increase self-reliance through accessibility to social services. Uganda’s inclusive refugee hosting policies have taught us a valuable lesson: it’s important to give refugees a form of self-settlement through self-reliance. By maintaining agency in accessing services like education and healthcare, both refugees and hosts can benefit from refugee-related aid. Additionally, low-income countries can benefit from the increased allocation of aid.

While Uganda has become a successful example of refugee integration for other countries to follow, unfortunately UNHCR and its partners are now facing substantial funding cuts. Without the financial support of the international community, the Ugandan government is considering repealing some of its inclusive policies and turning refugees away. Our study underscored the importance of resource allocation and integration policies for host-refugee relations. We are deeply concerned that in a less hospitable policy environment, the positive effects and lack of backlash against refugees we found in our research may well reverse.

References

Dancygier, R, N Egami, A Jamal, and R Rischke (2020), “Hate crimes and gender imbalances: fears over mate competition and violence against refugees”, American Journal of Political Science.

Ronald, M A (2022), “An assessment of economic and environmental impacts of refugees in Nakivale, Uganda”. Migration and Development, 11(3): 433-449

UNHCR (2020), “Global Trends in Forced Displacement in 2020”, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Technical report.

Zhou, Y Y, G Grossman, S Ge (2023) “Inclusive refugee-hosting can improve local development and prevent public backlash”, World Development, 166: 106203.