Increasing the cost of informal employment raised formalisation rates for workers at formal firms. However, it also led to a large, persistent drop in firm size. There is a trade-off between higher formalisation rates for current employees and lower formal job-finding probabilities for job seekers.

Informal employment is a significant issue in emerging and developing countries, with 61% of the world's workforce engaged in the informal economy (ILO 2018). Despite numerous policies worldwide designed to enforce labour regulations and increase non-compliance costs, monitoring may lead to unexpected outcomes on formal employment, wages, and worker welfare. Monitoring can improve compliance with mandated social benefits thus making formal jobs more attractive and increasing formalisation (Ronconi 2010, Almeida and Carneiro 2012). However, strengthening “pro-worker” regulations can also lead to higher labour costs for employers, suppressing labour demand and output, and potentially affecting productivity and employment (Besley and Burgess 2004).

In our research (Samaniego de la Parra and Fernandez Bujanda 2024), we examine how increasing the cost of informal employment affects formal-sector firms and workers in Mexico. Even formal firms can engage in tax evasion either by under-reporting profits, wages, or workforce size (Verhoogen 2017). We focus on firms that are already registered with the government (i.e. formal firms) and distinguish between the short- and medium-term effects for currently employed informal employees and their formal co-workers.

Informal workers in the formal sector in Mexico

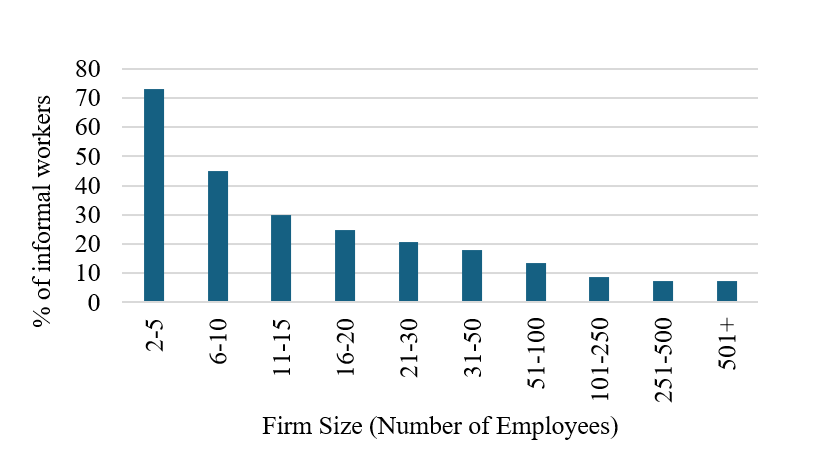

In Mexico, one out of every four workers in a formal firm is informally employed. A stylised fact in the informality literature is that smaller firms are more likely to be informal (De Paula and Scheinkman 2011, Busso et al. 2012, Ulyssea 2018, Bobba et al. 2021). We further show that the share of informal employment within formal firms is also decreasing in firm size. The negative relationship between share of informal employment and firm size holds across all sectors of the economy.

Figure 1: The share of informal workers by firm size

Informal jobs are significantly less stable than formal jobs in Mexico

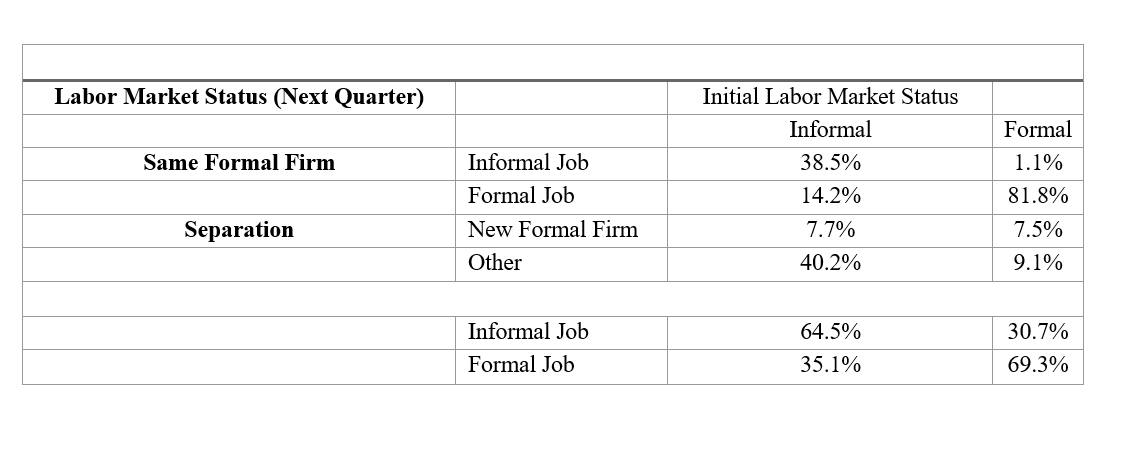

Informal jobs are less stable than formal jobs, even after controlling for worker and firm characteristics. Separation probabilities are almost three times higher for informally employed individuals relative to their formally employed co-workers. However, within-firm transitions from informal to formal jobs are not rare among formal firms’ employees. The quarterly predicted probability of transitioning from an informal to a formal job, without changing employers, is on average 14%.

Figure 2: Within-Firm Transitions and Separations by Initial Formality Status

The challenges of measuring informal employment

Analysing informal employment is challenging for at least two reasons:

- Informal employment is, by definition, hidden and missing from administrative data commonly used for policy evaluation.

- Transitions to informality are not random making it challenging to disentangle the effects of enforcement on firms’ labour demand from other underlying factors that jointly determine firms’ decisions and their exposure to enforcement.

We rely on over 480,000 random worksite inspections performed by Mexico's Ministry of Labor and Social Welfare (STPS) to address these challenges. These inspections increase the expected costs of informal employment by raising the likelihood of a follow-up visit and the size of fines imposed by the Social Security Institute (IMSS). Because worksites are randomly selected, the increase in the costs of informal employment is unrelated to the firm’s characteristics. Therefore, we can identify the causal impact of enforcement on firms’ and workers’ outcomes.

We create two novel datasets. First, we merge the roster of firms used by the Ministry of Labor and Social Welfare when selecting worksites for inspection with a rotating panel household survey (ENOE). This data allows us to observe both formal and informal employment spells for a large, representative sample of households in Mexico and track workers’ transitions between informal and formal jobs. Further, we can distinguish changes in formality status within the same firm from those that occur when a worker switches employers.

Second, we also merge the roster of firms eligible for inspection with administrative employer-employee matched records from the Social Security Institute. The administrative dataset allows us to track workers during their formal employment tenure at formal-sector firms.

How does increasing the cost of informal employment affect formal-sector firms and workers in Mexico?

Increasing the cost of informal employment via inspections did not affect firm survival probability, on average. Enforcement did not lead firms to exit the formal sector, even for firms with less than five employees. However, inspections led to a persistent decrease in formal employment at inspected firms, with formal employment dropping by 11% a year after an inspection compared to firms that weren't inspected. This gap widened to 15% after 18 months.

The decrease in formal employment was primarily due to a decline in formal hiring and an increase in separations, especially in smaller firms.

For workers who were informally employed at the time of the inspection, the probability of transitioning to a formal job at the same firm increased by 13.7 percentage points during the quarter of inspection. In other words, the likelihood of within-firm formalisations doubled after an inspection. Moreover, formal job finding rates with a new employer also increased for employees at inspected worksites relative to comparable workers at non-inspected firms. We interpret this finding as consistent with new employers using the worker's current formality status as a signal to determine the type of contract to offer.

Formal workers saw a temporary increase in job stability and wages. The likelihood of remaining formally employed at the inspected firm increased by 3.6 percentage points, and wages rose by about 6%. However, these effects dissipated after six months, and the probability of continued employment declined by 4.7 percentage points.

Making sense of worker-level formalisations and firm-level reductions in formal employment

Our findings show that increasing the cost of informal employment immediately after the inspection decreases informality at the inspected firm by reducing the number of existing (and potentially new) workers with informal contracts. Thus, formalisation rates go up for informally employed workers at the time of the inspection (now and with potential future employers). However, by reducing the pool of informal workers, enforcement shuts down a critical channel for formal employment growth: within-firm informal-to-formal job transitions. This reduction in inflows, combined with a decline in new formal job creation, led to an overall decline in the formal workforce size at inspected firms.

Policy implications for raising formal employment

Over the past decade, there have been various efforts to improve labour law enforcement in Mexico, including the constitutional reforms to the Labor Law in 2017, the joint CAMINOS project between the US and Mexico, and the labour law enforcement provisions in the United States-Mexico-Canda Agreement. The results outlined in this article abstract from general equilibrium effects which are relevant for nation-wide enforcement actions such as those listed above, but nonetheless provide valuable insights into the effects of increasing enforcement at individual firms. In particular, policy design should account for the dynamic nature of formal employment and the inherent trade-offs between current formalisation and future job finding rates. This requires, first, acknowledging that enforcement increases informal-to-formal job transitions, but simultaneously increases flows from informality to unemployment. Enforcement actions must be designed to limit firms’ ability (and incentives) to avoid punishment via temporary informal job destruction.

Second, policy makers must note that high hiring and firing costs for formal workers create incentives for informal jobs to serve as steppingstones to formal contracts at formal firms. Enforcement reduces the pool of workers available for these formalisations and hence can negatively impact aggregate formal employment. Enforcement actions coupled with policies which reduce the cost of formalisation can decouple the use of informal contracts as “trial-periods” and hence reduce the trade-offs between current formalisation and future job finding rates.

Editor’s Note: Read our VoxDevLit on Informality that summarises a wide range of studies ranging from well-identified empirical analyses to macro and structural equilibrium models of informality.

References

Bobba, M, L Flabbi, S Levy, and M Tejada (2021), “Labor market search, informality, and on-the-job human capital accumulation,” Journal of Econometrics, 223(2): 433–453.

Besley, T, and R Burgess (2004), “Can labor regulation hinder economic performance? Evidence from India,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(1): 91–134.

Busso, M, S Levy Algazi, and M V Fazio (2012), “(In)formal and (Un)productive: The productivity costs of excessive informality in Mexico,” Inter-American Development Bank Working Paper Series No. IDB-WP-341.

De Paula, Á, and J A Scheinkman (2011), “The informal sector: An equilibrium model and some empirical evidence from Brazil,” Review of Income and Wealth, 57(S1): S8–S26.

Samaniego de la Parra, B, and L Fernández Bujanda (2024), “Increasing the cost of informal employment: Evidence from Mexico,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 16(1): 377–411.

Verhoogen, E (2017), “Improving payroll-tax compliance through decentralized monitoring: Evidence from Mexico,” VoxDev Article.

Ulyssea, G (2018), “Firms, informality, and development: Theory and evidence from Brazil,” American Economic Review, 108(8): 2015–2047.