Data from 60 countries across six continents reveals that, in almost every country, the support for basic rights is underestimated, especially among men, suggesting that aligning perceived and actual views may be a promising policy intervention to raise female labour force participation

Editor's note: This article originally appeared on VoxEU.

Around the world, economic opportunities and outcomes vary widely between women and men. In some contexts, especially in developing countries, women are denied basic economic freedoms, such as the ability to work outside the home (Kerr et al. 2013). Other countries provide women with more formal rights, and, even there, women are underrepresented in the top echelons of economic (Pavelin et al. 2012) and political leadership. An extensive body of literature has indicated that gender norms are crucial determinants of differences in economic outcomes between men and women (Fernández 2007, Jayachandran 2015, Field et al. 2021). Such norms are often deeply engrained and slow to change (Giuliano et al. 2011, Alesina et al. 2017).

Recent work has documented that misperceptions of norms may exacerbate gender inequality and restrict women's freedom in Saudi Arabia. The vast majority of men in Saudi Arabia privately support women working outside the home but underestimate the extent to which others share this view. A simple informational intervention designed to realign perceived norms with true attitudes corrects misperceptions and instigates rapid behaviour changes (Bursztyn et al. 2022).

While the findings from the Saudi Arabia study are encouraging, a natural question is whether such misperceptions are widespread or confined to a specific and somewhat unique context. In a recent paper (Bursztyn et al. 2023), we tackle this question from a global perspective. We use new nationally representative data from 60 countries across six continents, collected through the World Gallup Poll in 2020, to measure actual and perceived gender norms and characterise the nature of misperception across countries along the spectrum of gender equality.

Measurement

To investigate norms that are relevant in contexts with different degrees of gender inequality, we focus on two distinct margins:

- support for basic rights for women, measured by the agreement with the statement: “Women should have the freedom to work outside of the home.”

- support for affirmative action, measured by the agreement with the statement: “The government and companies should give priority to women when hiring for leadership positions.”

Each study participant was randomly asked to respond to one of the above two statements. The participants’ responses then capture the actual gender norms in each country. Extensive testing and multiple quality checks, including a list experiment, were conducted to exclude the presence of systematic biases in the measurement of actual norms.

Crucially, we then seek to measure perceived gender norms. Participants were asked to separately estimate how many women and how many men out of a random sample of 100 would say they agree with one of the above statements. To rule out that desirability bias may drive a potential mismatch between actual and perceived norms, the survey randomly asked some participants how many women and how many men truthfully agreed with the statement, but no systematic difference was detected in the answers to these two formulations.

After measuring actual and perceived gender norms, we can characterise misperceptions, defined as the difference between these two variables.

Actual gender norms

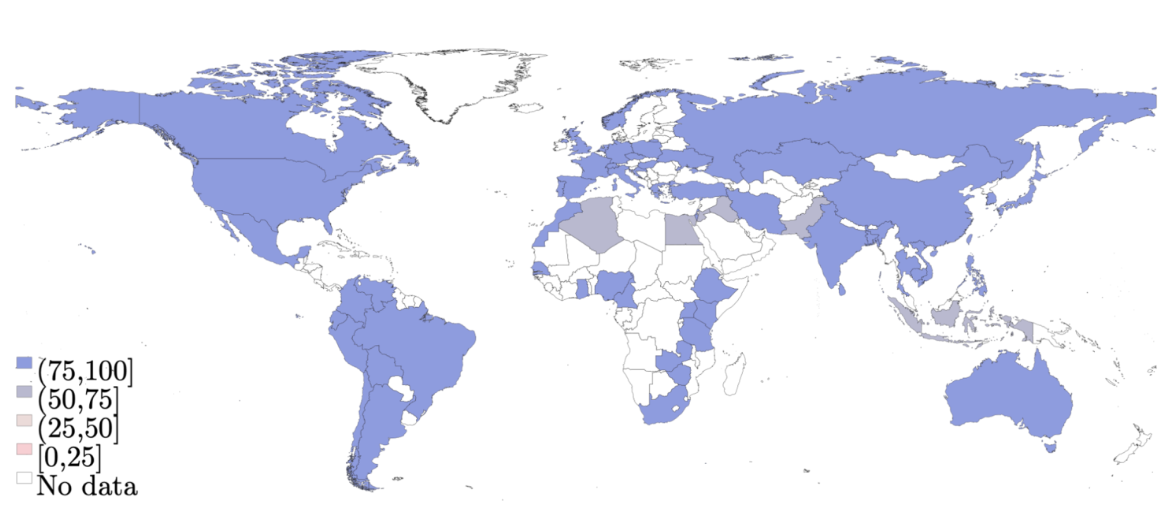

Support for women’s basic rights, i.e. freedom to work outside the home, is widespread: the majority of men and an even larger fraction of women support it in each of the 60 countries included in the study (Figure 1). There is substantial heterogeneity in gender differences in the support for such basic rights. In countries that are often classified as having wide gender disparities, like Jordan and Algeria, women are on average 30 percentage points more likely to support women’s freedom to work outside the home compared to men. This gender gap almost vanishes and there is close to consensus support for basic rights in countries where gender disparities are smaller, like Canada and Norway.

Figure 1 Actual support for basic rights around the world

Notes: This is Figure 2 (Panel a) in Bursztyn et al. (2023). The map shows average support (%) for basic rights in each country, pooled across men and women. Data: Gallup World Poll 2020, country-level. Geo data from Belgiu (2015).

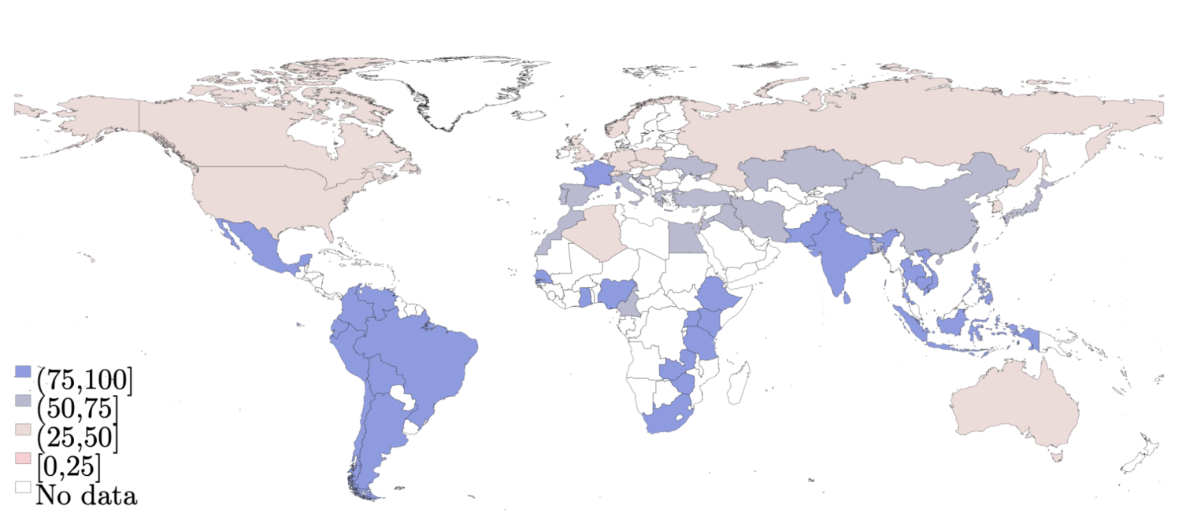

In contrast, support for gender-based affirmative action is far from universal: it is the majority view in 37 out of 60 countries, but the minority elsewhere (Figure 2). Perhaps surprisingly, the countries where gender disparities are smaller exhibit lower levels of support for the notion that government and businesses should give priority to women when hiring for leadership positions. As is the case for basic rights, women tend to support such a view more often than men across the vast majority of countries in the sample.

Figure 2 Actual support for affirmative action around the world

Notes: This is Figure 2 (Panel b) in Bursztyn et al. (2023). The map shows average support (%) for affirmative action in each country, pooled across men and women. Data: Gallup World Poll 2020, country-level. Geo data from Belgiu (2015).

Misperceived gender norms

How do people’s perceptions of gender norms match the actual gender norms described above? And how are men's and women’s views perceived relative to their actual responses? Our main contribution is to shed light on these questions.

The short answer is that misperceptions are ubiquitous. Interestingly, though, the direction and the magnitude of such misperceptions vary in crucial ways. We establish four stylised facts.

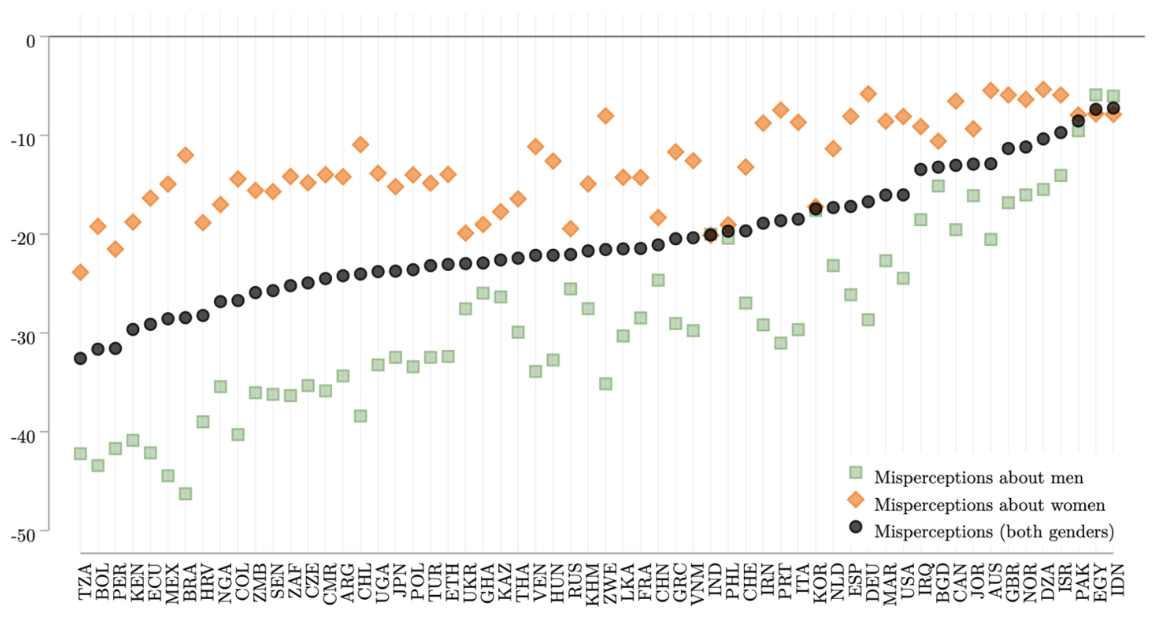

The first two stylised facts involve the support for women’s basic right to work outside the home. First, there is a universal underestimation of support for women’s basic rights, suggesting that what was found by Bursztyn et al. (2022) in Saudi Arabia may hold in many other contexts (Figure 3). Second, while both men and women are believed to be even less supportive of basic rights than they truly are, support among men is most underestimated. For example, in Tanzania and Turkey, more than 80% of men support women's freedom to work outside of the home, but this is believed to be a minority view.

Figure 3 Global misperceptions about support for basic rights

Notes: This is Figure 6 (Panel a) in Bursztyn et al. (2023). The graph shows average misperceptions about support (pp) for basic rights among women (orange), among men (green), and pooled across gender (gray), in a given country. Misperceptions are defined as the difference between a respondent’s perception of the support for the respective policy in their country and the actual support in their country. A positive (negative) value indicates that support is overestimated (underestimated). Data: Gallup World Poll 2020, country-level.

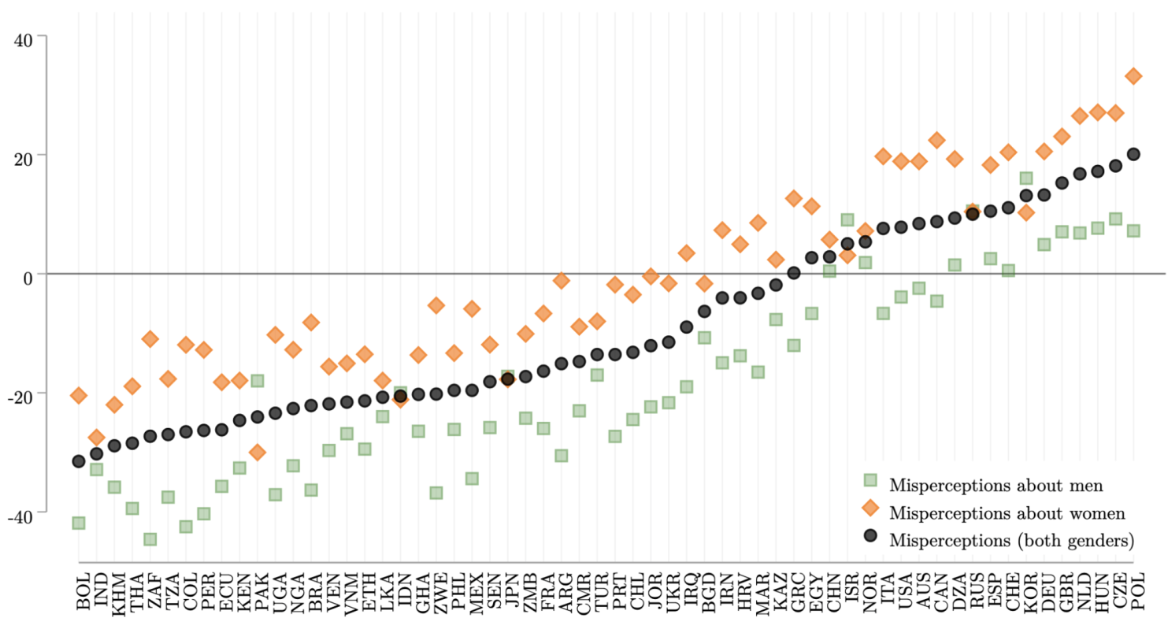

Regarding gender-based affirmative action, the third stylised fact indicates that people tend to overestimate support for gender-based affirmative in more gender-equal countries, while they underestimate it in less gender-equal countries (Figure 4). Fourth, misperceptions about the support for affirmative action are mostly driven by people overestimating women's support for this policy in more gender-equal countries and underestimating men's support in less gender-equal countries. As an example, we can compare South Africa and Canada. In South Africa, more than 90% of men support gender-based affirmative action, while the perception is that only a minority of men do; in contrast, in Canada, people believe that almost 70% of women support affirmative action, while it is, in fact, a minority view among them. This surprising finding highlights that misperceptions of gender norms in some situations may contribute to sustaining gender policies that are not necessarily favoured by women themselves.

Figure 4 Global misperceptions about support for affirmative action

Notes: This is Figure 6 (Panel b) in Bursztyn et al. (2023). The graph shows average misperceptions about support (pp) for affirmative action among women (orange), among men (green), and pooled across gender (gray), in a given country. Misperceptions are defined as the difference between a respondent’s perception of the support for the respective policy in their country and the actual support in their country. A positive (negative) value indicates that support is overestimated (underestimated). Data: Gallup World Poll 2020, country-level.

Taken together, the four stylised facts about misperceptions suggest that the societal equilibrium in many countries may change quickly if people's perceptions about the gender norms in society are corrected. More work is needed, of course, to provide validation to this hypothesis.

Mechanisms: Stereotyping and minority overweighting

In the final part of the paper, we present two mechanisms that together can account for the four stylized facts described above.

The first mechanism that appears to drive misperceptions at the country level is minority overweighting: the views of the minority appear to be given systematically more relevance in people’s perceptions of gender norms compared to the actual gender norms, irrespective of what the minority view is. The paper proffers the example of Zimbabwe and the Netherlands, two countries on opposite ends of the global spectrum of gender equality. In Zimbabwe, the majority (around 80%) of the population supports women’s freedom to work outside the home, whereas the perceived support is only around 60%. In the Netherlands, only a minority (around 30%) supports gender-based affirmative action, but the perceived support is closer to 50%. In both countries, like in most countries in the sample, perceptions appear to overweight the minority view compared to the majority view. Multiple forces may drive the tendency toward minority overweighting may arise, including outdated views, media coverage of minority views, or cognitive phenomena.

The second mechanism that appears to drive the perceptions of men’s and women’s views in the data is stereotyping (Bordalo et al. 2016 and 2019, Tabellini et al. 2021, Exley et al. 2022): while men are indeed less supportive of basic rights and affirmative action compared to women, such differences are exaggerated in people’s perceptions. In Zimbabwe, for example, actual support for basic rights is 15 percentage points smaller among men than among women, and perceived support is 41 percentage points smaller. Similarly, in the Netherlands, actual support for gender-based affirmative action is 6 percentage points smaller among men than among women, and it is perceived to be 26 percentage points smaller. These differences lead to an underestimation of men’s support for basic rights in Zimbabwe and an overestimation of women’s support for affirmative action in the Netherlands. In the vast majority of countries in the sample, perceptions about women’s support for basic rights and affirmative action are further distorted upward compared to perceptions about men, in line with the logic of gender stereotyping (Facchini et al. 2022).

Discussion

Our study shows that, in almost every country, the support for basic rights is underestimated, especially among men. This result suggests that aligning perceived and actual views may be a promising policy intervention to raise female labour force participation, especially in contexts where men have a significant say in women’s labour supply decisions or in their career outcomes. Such interventions could shift perceived social norms closer to the actual opinions in each community.

Misperceptions about the support for gender-based affirmative action have more complex potential implications. In more developed and gender-equal countries, the largest misperception is an overestimation of the support for affirmative action by women, who appear lukewarm about such a policy despite being its potential beneficiaries. More work is needed to understand why women hold these views, and what could be done to design these policies to minimise their costs to women and minorities.

Importantly, across countries and types of norms or policies, there appears to be much more convergence of opinions between men and women than people perceive. This finding highlights the importance of creative data collection on gender attitudes and perceptions.

References

Alesina, A, P Giuliano, and N Nunn (2013), “On the Origins of Gender Roles: Women and the Plough”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 128(2): 469–530.

Belgiu, M (2015), “UIA World Countries Boundaries”, UNIGIS International Association.

Bordalo, P, K B Coffman, N Gennaioli, and A Shleifer (2019), “Beliefs About Gender”, American Economic Review 109(3): 739–73.

Bordalo, P, K Coffman, N Gennaioli, and A Shleifer (2016), “Stereotypes”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 131(4): 1753–1794.

Bursztyn, L, A L González, and D Yanagizawa-Drott (2020), “Misperceived social norms: Women working outside the home in Saudi Arabia”, American Economic Review 110(10): 2997–3029.

Bursztyn, L, A W Cappelen, B Tungodden, A Voena and D H Yanagizawa-Drott (2023), “How Are Gender Norms Perceived?”, NBER Working Paper No. 21049.

Exley, C L, O P Hauser, M Moore, and J-H Pezzuto (2022), “Beliefs about Gender Differences in Social Preferences”, Harvard Business School Working Paper No. 22-079.

Facchini, G, V Rueda and M Eberhardt (2022), “Women are "hardworking", men are "brilliant": Stereotyping in the economics job market”, VoxEU.org, 8 February.

Fernández, R (2007), “Women, work, and culture”, Journal of the European Economic Association 5(2-3): 305–332.

Field, E, R Pande, N Rigol, S Schaner, and C Troyer Moore (2021), “On her own account: How Strengthening Women’s Financial Control Impacts Labor Supply and Gender Norms”, American Economic Review 111(7): 2342–75.

Giuliano, P, N Nunn and A Alesina (2011), “Women and the plough”, VoxEU.org, 2 July.

Jayachandran, S (2015), “The roots of gender inequality in developing countries”, Annual Review of Economics 7(1): 63–88.

Kerr, W, S O'Connell and E Ghani (2013), “What explains gender differences in India? What can be done to promote shared prosperity?”, VoxEU.org, 22 February.

Pavelin, S, I Tonks and J Grosvold (2012), “Gender diversity on company boards”, VoxEu.org, 27 March.

Tabellini, M, D Y Yang and P Bordalo (2021), “Issue salience and political stereotypes”, VoxEU.org, 20 January.