The ‘Meet your Future’ programme in Uganda improved employment outcomes for young job-seekers by fostering realistic job expectations

Youth unemployment is an urgent global issue, particularly in Africa, where one out of every five first-time job seekers reside. Investing in upskilling young people has been one of the main policy responses (McKenzie 2017). Whilst these programmes have been effective in certain contexts for promoting employment, they frequently exhibit low job-placement rates, thereby failing to tap the vast pool of untapped talent (Alfonsi et al. 2020, Maitra and Mani 2017, Bandiera et al. 2022). A plausible explanation is the significant impediment posed by supply-side information barriers, especially in low-income environments. Young job seekers may lack knowledge of various aspects of the job search process, such as identifying job openings, applying for positions, and preparing for job interviews. The lack of such vital information is frequently accompanied by an overly optimistic outlook regarding employment prospects, causing individuals to reject low-paying jobs in pursuit of greater opportunities that frequently do not materialise (Groh et al. 2016, Abebe et al. 2021, Banerjee and Chiplunkar 2022, Bandiera et al. 2022). This prompted us to investigate whether assisting young job seekers in forming realistic expectations of jobs available on the labour market and enhancing their understanding of the search process would lead to an improvement in the quality of their initial match and career trajectory.

Meet Your Future: Tailored, relevant, credible, and low-cost information

We created "Meet Your Future," a mentoring programme that pairs soon-to-be graduates of vocational training institutes (VTIs) with successful young workers for individualised mentoring sessions. Incorporating key findings from the interdisciplinary literature on messenger effects and job referrals, the programme highlights the persuasive power of messengers who share similar characteristics with their recipients (Durantini et al. 2006, Dolan et al. 2012). In addition, recognising the importance of connections in informal labour markets, we sought to incorporate these insights into the design of the programme. We therefore meticulously selected mentors from among recent graduates of VTIs and specialised fields. This deliberate choice was made to facilitate effective mentoring by establishing a relatable and comfortable mentor-student relationship. By connecting students with mentors who have first-hand knowledge of the local labour market, we ensure that the information shared is not only credible and pertinent but also tailored to the specific context.

In an effort to determine the efficacy of MYF, we conducted a three-year randomised control trial with 1,112 vocational students in urban Uganda and closely monitored their progress (Alfonsi et al. 2022). The approximately 20-year-old students received two years of training in one of thirteen specialised fields, such as catering, plumbing, and tailoring. Innovative questionnaires were utilised to glean information from both students and mentors in order to collect exhaustive data. In a novel approach, we also analysed the content of the conversations between students and mentors by using voice recordings.

Young jobseekers' unawareness of labour market entry conditions and dynamics

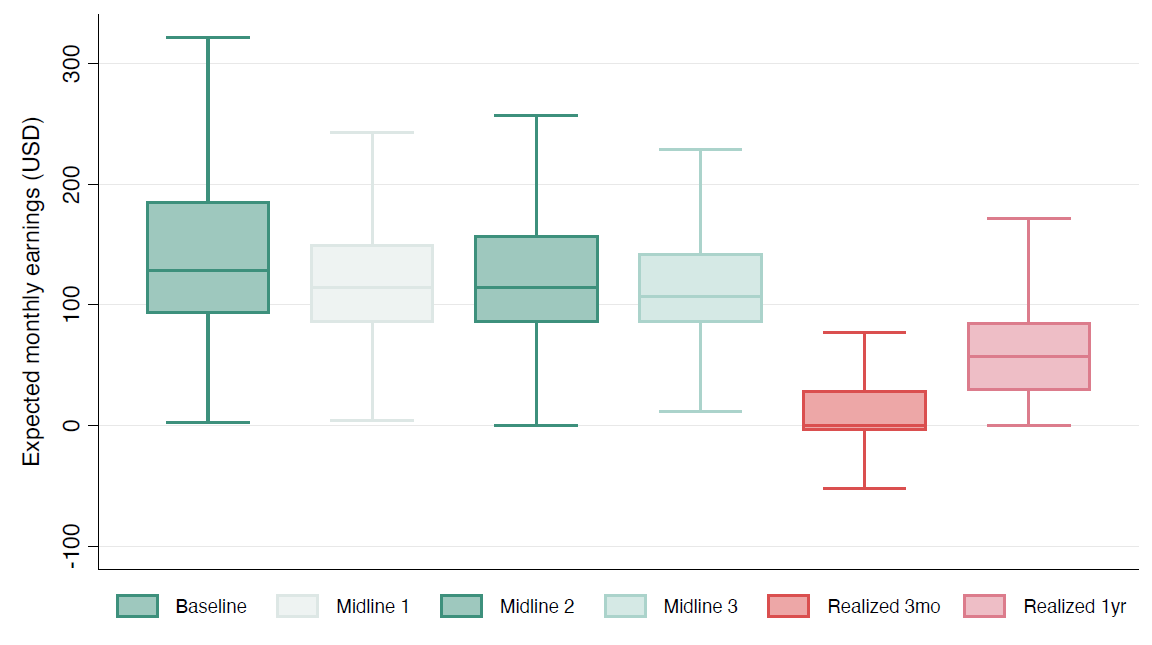

In accordance with recent research, our study replicates a pattern of striking overoptimism regarding entry-level pay among jobseekers. 94% of students overestimate their anticipated earnings from their first job. The reality, however, paints a starkly different picture, with first-job earnings averaging only 14% of their initial expectations. This proportion rises to 65% when comparing expectations to earnings one year later. This demonstrates that the overoptimism in wages primarily revolves around their initial job, as students often fail to acknowledge the prevalence of unpaid or low-paying positions.

Despite the fact that 52% of the cohort's first jobs are unpaid, only 21% of students express a willingness to accept an unpaid position as their initial job. This discrepancy, along with their limited understanding of job-to-job transition probabilities, the value of experience, and the potential for salary growth, highlights a significant insight. Not only do new entrants harbour exaggerated optimism about their starting salaries, but they also lack a comprehensive understanding of the dynamics involved in transitioning between jobs. Importantly, students undervalue the significance of unpaid internships, failing to recognise them as valuable stepping stones toward better opportunities in the future.

Figure 1: Overoptimism

Unleashing positive impacts on employment and earnings three months and one year later

Our findings reveal a discouraging reality for trainees. Within our control group, 21% of graduates left the workforce within three months, resulting in underutilisation of skills and difficulty finding stability in their chosen specialisations. The remaining individuals experienced frequent transitions between informal jobs, indicating a lack of stability and consistency.

In this context, Meet Your Future was especially effective at improving employment outcomes. We identify substantial positive effects on employment three months after the transition from school to work. Participation in the labour market is 27% greater among treated students; these students obtain their first jobs more quickly and are 33% more likely to utilise and advance their acquired skills through vocational education. These accelerated first employment periods allow students to ascend the career ladder faster. Treated students are more likely to be retained and promoted in their first job, more likely to transition from one job to another, and their earnings are 18% higher than those of the control group one year after the intervention.

Conversational content and mechanisms driving programme success

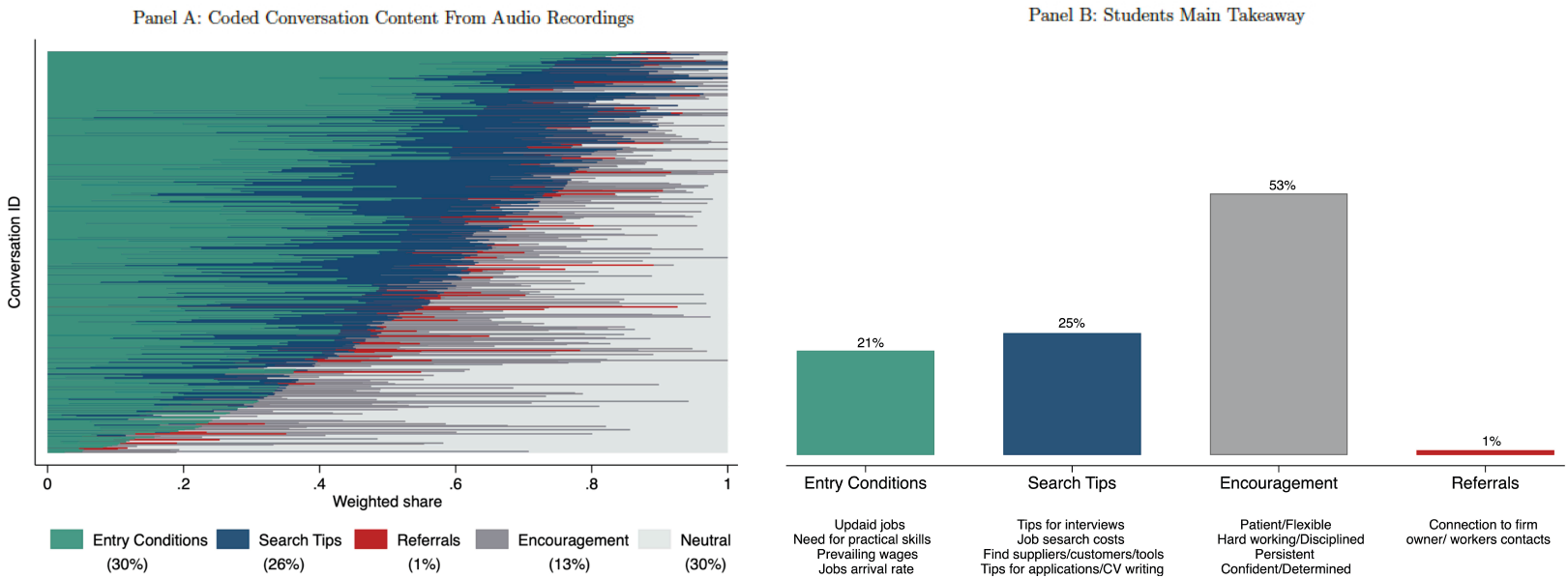

To understand the success of our programme, we analyse conversation data. Drawing from existing literature and recorded conversations, we identify four mechanisms that drive the intervention's impact on labour market outcomes: job referrals, search tips, information on entry-level conditions, and encouragement. Through detailed analysis of coaching session transcripts and additional data, we connect the conversation content to these mechanisms. Figure 2 presents the raw conversation content and insights into students' key takeaways.

Our findings highlight the significance of mentorship as a potent source of information and encouragement. Mentoring helps students re-evaluate their overly optimistic views of the job market, leading to lower expectations and a recognition of the significance of early employment for future opportunities. Students become more adaptable in terms of wage expectations and less inclined to reject job offers, in contrast to previous efforts that resulted in discouragement. Surprisingly, our analysis reveals that direct job referrals or improved search abilities are not the primary factors driving the observed positive effects.

Figure 2: Conversation content and students' key takeaways

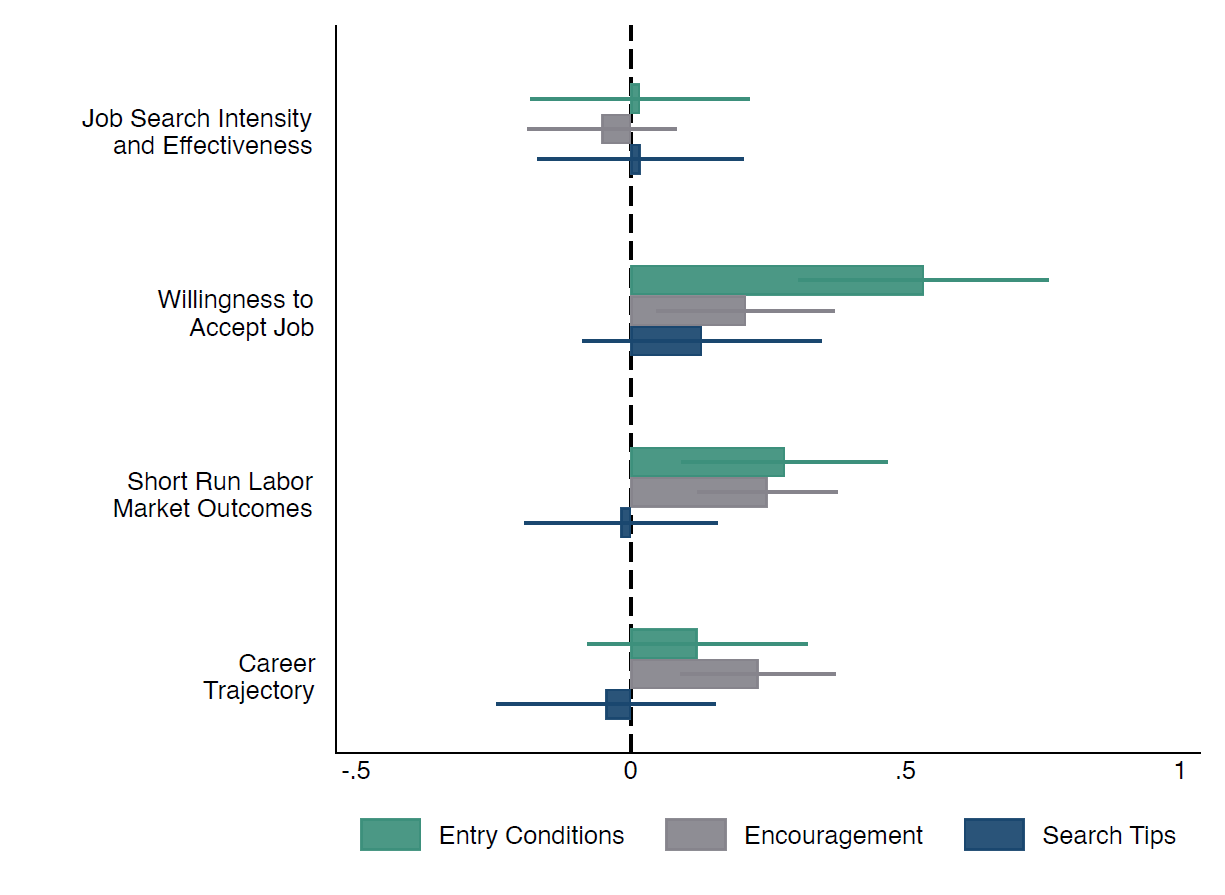

We leverage a second-level randomisation, namely that to the mentors, and combine it with empirical bayes and instrumental variables approaches to reaffirm our previous findings and confirm that learning about entry-level market conditions and recognising the future value of present job opportunities are the crucial mechanisms through which the MYF programme influences individuals' job search behaviour and significantly affects their labour market outcomes. By analysing the impact of each conversation topic, we uncover the effectiveness of mentors who provide information on entry-level conditions and offer encouragement to their mentees.

Figure 3: Type of support provided and labour market outcomes

Closing thoughts: Correcting distorted beliefs for improved career advancement

Our research brings to light the crucial role played by distorted beliefs as a significant pathway through which information frictions hinder career advancement. By correcting overly optimistic beliefs, our findings underscore the importance of striking a delicate balance between delivering unfavourable news and instilling hope for better future outcomes. This balance is key to preventing discouragement, labour force dropout, and, particularly among skilled workers, the wastage of valuable human capital.

References

Abebe, G, S Caria, M Fafchamps, P Falco, S Franklin, S Quinn, and F Shilpi (2021), “Matching Frictions and Distorted Beliefs: Evidence from a Job Fair Experiment.” Department of Economics, Oxford University (mimeo).

Alfonsi, L, M Namubiru, and S Spaziani (2022), “Meet Your Future: Experimental Evidence on the Labor Market Effects of Mentors." Working Paper.

Alfonsi, L, O Bandiera, V Bassi, R Burgess, I Rasul, M Sulaiman, and A Vitali (2020), “Tackling Youth Unemployment: Evidence From a Labor Market Experiment in Uganda.” Econometrica, 88(6):2369-2414.

Bandiera, O, V Bassi, R Burgess, I Rasul, M Sulaiman, and A Vitali (2022). “The Search for Good Jobs: Evidence from a Six-year Field Experiment in Uganda.” Technical report, Working Paper.

Banerjee, A and G Chiplunkar (2022), “How Important are Matching Frictions in the Labour Market? Experimental & Non-experimental Evidence from a Large Indian Firm.” Money.

Dolan, P, M Hallsworth, D Halpern, D King, R Metcalfe, and I Vlaev (2012), "Influencing behaviour: The mindspace way." Journal of Economic Psychology, 33(1): 264-277.

Durantini, M R, D Albarracín, A L Mitchell, A N Earl, and J C Gillette (2006), "Conceptualizing the influence of social agents of behavior change: A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of hiv-prevention interventionists for different groups." Psychological bulletin, 132(2): 212-248.

Groh, M, N Krishnan, D McKenzie, and T Vishwanath (2016), “Do wage subsidies provide a stepping-stone to employment for recent college graduates? Evidence from a randomized experiment in Jordan.” The Review of Economics and Statistics, 98(3): 488-502.

Maitra, P and S Mani (2017), “Learning and earning: Evidence from a randomized evaluation in India.” Labour Economics, 45(C): 116-130.

McKenzie, D (2017) “How Effective Are Active Labor Market Policies in Developing Countries? A Critical Review of Recent Evidence.” The World Bank Research Observer, 32(2): 127-154.