A unique Bolivian law that legalised and regulated the work of young children led to unexpected declines in child employment without improving working conditions.

Disclaimer: This blog's findings, interpretations, and conclusions are entirely those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of the Allegheny County Department of Human Services.

Worldwide, over 160 million children engage in child labour, with roughly half performing hazardous work (International Labour Organization 2021). While most policy efforts focus on preventing child work through bans (e.g. Bargain and Boutin 2021, Bharadwaj et al. 2020, Piza et al. 2023, Kozhaya and Flores 2024, Edmonds and Shrestha 2012), little attention has been paid to policies that aim to improve the working conditions of children or that try to bring child workers “out of the shadows”. More broadly, little is known about the effectiveness of policies to protect workers that are typically hired informally, whose participation in labour markets is often socially condemned and rarely legally recognised.

In 2014, Bolivia took an unprecedented approach by legally recognizing the work of children as young as 10 years old while simultaneously extending worker protections to working children similar to those granted to adults. This unique setting allows us to examine how policies regulating working conditions affect markets characterised by informality and social stigma. We study the effects of this law on children’s work in Lakdawala, Martínez, and Vera-Cossio (2025).

The 2014 child labour law in Bolivia and its implementation

The 2014 law introduced two major changes: it lowered the de facto minimum working age from 14 to as young as 10 (with age-specific restrictions on the type of work allowed) and extended formal worker protections and rights to younger workers. Children aged 12-13 could work for others with parental permission and authorisation from local offices, while those aged 10-11 could engage in self-employment. These younger workers became entitled to the same benefits as adult workers, including minimum wages and social security.

To ensure enforcement, the government tasked local offices of the Ministry of Labor and Social Protection (MTEPS) with adding child labour inspections to their regular labour and workplace inspections; as a result, child labour inspections more than doubled between 2013 and 2017. Awareness of the policy change appears to have been widespread, as evidenced by coverage of the law in national and international news outlets and by recorded attendance of official workshops conducted by the MTEPS to educate children, parents, and employers about the law. Amid high levels of public scrutiny, the key features of the law formally recognising the work of younger children were reversed in 2018.

Legalising child labour had surprising effects on child employment

To estimate the effects of the law, we use detailed household survey data from 2012-2019 and compare children just under the age of 14 – whose work was newly legalised and regulated under the 2014 law – to those just over the age of 14, whose work was unchanged by the 2014 law. Furthermore, we make these comparisons across three time periods: before the law was enacted (2012-2013), during the law’s implementation (2014-2017), and after the law was reversed (2018-2019).

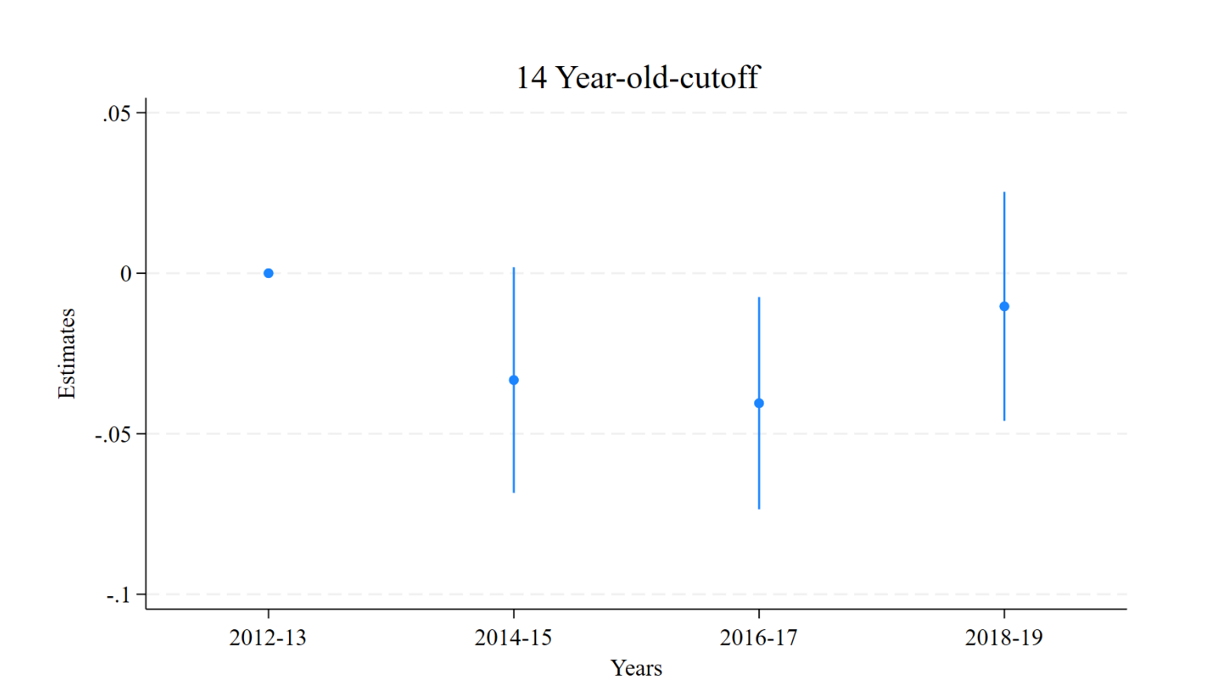

We find that contrary to expectations, the law reduced rather than increased child labour. Children under 14 were nearly 4 percentage points less likely to work when the law was in effect—roughly a 22% decline relative to pre-law levels (Figure 1). This decline was driven by a decrease in work for others rather than self-employment, and particularly in occupations that were legally allowed and regulated under the law. Importantly, there was no reallocation to prohibited occupations. These effects dissipated after key components of the law were reversed in 2018.

Figure 1: Difference between 13-year-old and 14-year-old work probabilities (2012-2019)

Note: The figure reports changes in work probabilities for 13-year-olds relative to 14-year-olds over time (grouped in two-year bins), with respect to the years preceding the policy change (2012-2013). The specification includes linear splines of the running variable, defined as the difference between the cutoff age and age a week before the survey date in months, as well as vector of control variables. The 95% confidence intervals are based on standard errors clustered at the age in months level.

The decline in work was particularly pronounced in areas closer to regional MTEPS offices, where enforcement through inspections was more likely. The effects were also concentrated in more visible forms of work, such as employment at fixed establishments, rather than less traceable forms of work like those that are mobile (e.g. street vending) or home-based activities. We find suggestive evidence that the law shifted children's time allocation toward schooling, though we observe no effects on overall enrollment, grade progression, or time spent on household chores.

Limited impacts on working conditions for children

Despite the law's aim to improve working conditions, we find no evidence that it enhanced job safety or reduced work-related injuries among children who remained employed. Prior to the law, over 65% of child workers were engaged in hazardous occupations and more than one-third reported suffering a work injury in the past year. The law may have modestly increased wages for working children, though this affected very few children as only a small fraction receives regular salaries.

Why did child employment decline in Bolivia?

The reduction in child work appears driven by employers' avoidance behaviour rather than improved working conditions. Most child workers are employed by informal firms that likely reduced hiring of younger children to avoid drawing attention from labour inspectors. This interpretation is supported by several findings:

- Effects were strongest in areas closer to labour ministry offices

- Declines were concentrated in visible forms of work

- Effects disappeared after the law's reversal

- There was no substitution toward adult or older sibling workers within households

These results align with evidence that firms respond to the threat of inspections even when not directly inspected themselves (Bertrand and Crépon 2021, Gagete-Miranda and Berlinski 2024).

Policy implications for regulating informal labour markets

Our findings highlight the complex challenges of regulating informal labour markets, particularly those involving vulnerable workers. While extending legal recognition and worker protections to child labourers may seem like a natural alternative to outright bans, our results suggest that such policies can have unexpected consequences. Further, neither policy approach (bans or regulation) directly addresses poverty—often considered the root cause of child labour—and both affect employers' incentives in nuanced and sometimes unexpected ways.

The Bolivian experience suggests that increased scrutiny of sensitive social issues, even without perfect enforcement, can significantly influence behaviour in informal markets. This insight may be valuable for policymakers considering approaches to addressing child labour and other challenging labour market issues in developing countries.

References

Bargain O, and D Boutin (2021), "Minimum age regulation and child labor: New evidence from Brazil," World Bank Economic Review 35(1): 234–260.

Bharadwaj P, L K Lakdawala, and N Li (2020), "Perverse consequences of well-intentioned regulation: Evidence from India's child labor ban," Journal of the European Economic Association 18(3): 1158–1195.

Bertrand M, and B Crépon (2021), "Teaching labor laws: Evidence from a randomized control trial in South Africa," American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 13(4): 125–149.

Edmonds E, and M Shrestha (2012), "The impact of minimum age of employment regulation on child labor and schooling," IZA Journal of Labor Policy 1(1): 1–28.

Gagete-Miranda J, and S Berlinski (2024), "Enforcement spillovers under different networks: The case of quotas for persons with disabilities in Brazil," Working paper series, Inter-American Development Bank.

International Labour Organization (2021), Child Labour: Global estimates 2020, trends and the road forward, New York: International Labour Office and United Nations Children's Fund.

Kozhaya M, and F M Flores (2024), "Child labor bans, employment, and school attendance: Evidence from changes in the minimum working age," World Bank Economic Review, lhae020.

Lakdawala L K, D Martínez Heredia, and D Vera-Cossio (2025), "The effects of expanding worker rights to children," Journal of Development Economics 172.

Piza C, A P Souza, P M Emerson, and V Amorim (2023), "The short- and longer-term effects of a child labor ban," World Bank Economic Review 38(2): 351–370.