Youth skill assessment increased employment and earnings for treated workseekers by providing information to both them and prospective employers

Globally, 67.6 million people aged 15-24 were unemployed in 2019 (ILO 2020a), and youth were three times more likely to be unemployed than adults. High unemployment, particularly for youth, may be exacerbated by ‘information frictions’ – that is, mistakes in firms’ hiring decisions or workseekers’ search decisions due to limited information.

Labour market information frictions

Limited information about workseekers' skills can lead firms to hire poorly-matched workers and offer wages that are either too high or too low given workers’ skills (Altonji and Pierret 2001, Arcidiacono, Bayer and Hizmo 2010, Kahn and Lange 2014). Limited information can also lead workseekers to search for jobs that poorly match their skills or prematurely end their search (Belot, Kircher and Muller 2018, Conlon, Pilossoph, Wiswall and Zafar 2018).

Young workseekers may be particularly vulnerable to information frictions, as they have less experience searching for work and working as well as fewer references from past jobs, which help provide information about the skills of older workseekers.

Information frictions may be more serious in developing countries, where hiring may be less formal and educational qualifications may provide less information about skills (Pritchett 2013).

Limited information may exacerbate other barriers to job search, including high search and migration costs (Abebe, Caria and Ospina-Ortiz 2020b, Bryan, Chowdhury and Mobarak 2014, Franklin 2017). In these contexts, simple and cheap interventions that provide more information about workseekers’ skills – such as skill certificates – may be valuable.

Assessing and certifying skills of youth in South Africa

In a new paper (Carranza, Garlick, Orkin and Rankin 2020), we show that assessing young workseekers’ skills, and helping both workseekers and firms to learn the assessment results, increases workseekers’ earnings and employment.

We recruited 6,891 workseekers in Johannesburg from low-income backgrounds through a partnership with the Harambee Youth Employment Accelerator, a South African social enterprise focused on youth employment. Respondents were 99% Black African, 62% female, and aged 18-29. Almost all respondents (99%) had completed secondary school, 17% had a university degree/diploma, and 21% had some other post-secondary education. Among them, 70% had previously worked, but only 9% had ever held a long-term job.

Over two days, participants completed six standardised assessments of their numeracy, communication (verbal and written), grit, focus, and planning skills. We randomly chose some participants to receive certificates describing the assessments and showing their results relative to other workseekers assessed by Harambee. The certificate was branded and included their name to provide credible information to prospective employers. We encouraged workseekers to use the certificates in job applications if they thought it would help them.

Increased earnings and job quality among certificate recipients

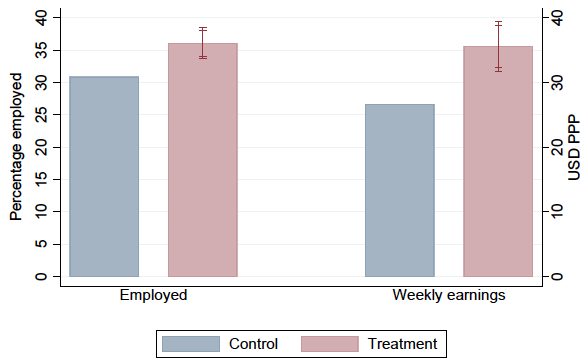

The intervention improved workseekers’ labour market outcomes in the following three to five months (Figure 1). Certification raised participants’ employment rate by five percentage points relative to the control group (36% versus 31%). Certification also increased participants’ earnings by 34% relative to the control group.

Treated participants earned more because they were more likely to be employed and earned higher hourly wages conditional on employment, not because they worked longer hours conditional on employment. The effect on wages, and a positive treatment effect on the probability of having a written employment contract, suggest certification increased participants’ job quality.

Figure 1 Treatment effects of public certificates on employment and earnings

Notes: Blue/left bar shows mean outcome for the control group. Red/right bar adds the treatment effect of the public certification intervention to the control mean. Capped lines show 90 and 95% confidence intervals. All outcomes use 7-day recall periods.

Effects on firms and workseekers

The employment and earnings effects may be due to information acquired by workseekers, firms, or both: We show that both firms and workseekers responded to the information provided, suggesting that both sides of the market lacked relevant information about workseekers’ skills. This implies interventions providing information about workseekers’ skills will be most effective if information is available to both sides of the labour market.

- Workseekers’ beliefs and behaviour

Information from these certificates shifted workseekers' beliefs and behaviour. Certification moved participants’ beliefs about their skills closer to their measured skills and made them more likely to search for jobs that most value the assessment in which they scored highest.

- Public versus private information

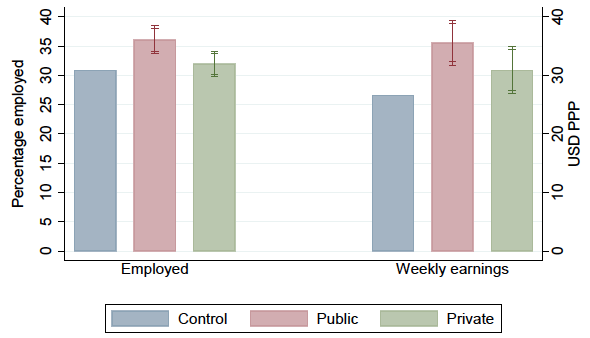

In a second experiment, we tested the effect of ‘private’ certificates, which showed participants their assessment results but without their names or any branding. These certificates were less likely to be credible to firms, so they mainly provided information to workseekers. Private certificates generated similar effects to the ‘public’ certificates on workseekers’ beliefs and search, and a smaller effect on earnings (Figure 2).

The fact that private information for workseekers changes their labour market outcomes, but by less than public information they can share with firms, suggests both sides of the market lacked relevant information about workseekers’ skills.

Figure 2 Treatment effects of public versus private certificates

Notes: Blue/left bar shows mean outcome for the control group. Red/middle bar adds the treatment effect of certification to the control mean. Green/right bar adds the treatment effect of getting private information to the control mean. Capped lines show 90 and 95% confidence intervals. All differences between public and private treatments are significant at 5% level. All outcomes use 7-day recall periods.

- Firm behaviour

We also provide direct evidence that information shifted firms’ behaviour: in a third experiment, we sent résumés directly to firms on participants’ behalf. We included public certificates with a random subset of résumés. Applications that included certificates received 11% more interview invitations, consistent with firms acquiring more information about workseekers’ skills from certificates.

Workseekers also believed that firms learned from the certificates. Among the participants who received public certificates, 70% used them in job applications and reported getting more interviews and job offers from applications they sent with reports.

Policy implications

This skill assessment and certification intervention improved employment and earnings by reducing the information frictions that affect both sides of the labour market in a developing country setting.

- The intervention easily passes a cost-benefit test.

The average effect on participants’ earnings in the first three months after treatment is 2.3 times the average variable cost of assessment and certification. The employment effect is larger than most short-run effects of job search assistance programmes covered in a recent meta-study (Card, Kluve and Weber 2018). This suggests that providing information about workseekers’ skills may be a valuable policy intervention and a cheap addition to existing job search assistance programmes.

- Understanding who faces information frictions can help guide policy design.

Other recent research has shown that skill assessments or reference letters can improve workseekers’ outcomes in the labour market (Abebe, Caria, Fafchamps, Falco, Franklin and Quinn 2020, Abebe, Burger and Piraino 2020, Bassi and Nansamba 2020, Pallais 2014). Unlike this previous work, our public certification, private certification, and audit experiments separately vary firms’ and workseekers’ information about assessment results, showing that both sides of the market face information frictions.

This shows that returns may be higher on interventions providing two-sided information, such as certification, than one-sided information, such as assessments by firms of job applicants’ skills or assessment-based career counselling by job search assistance programmes.

Authors’ note: A toolkit describing how an NGO or government could roll out the intervention can be found here.

Editors' note: This column is based on two PEDL projects. Found here and here.

References

Abebe, G, S Caria, M Fafchamps, P Falco, S Franklin, and S Quinn (2020), “Anonymity or Distance? Job Search and Labor Market Exclusion in a Growing African City”, Review of Economic Studies, forthcoming.

Abebe, G, S Caria, and E Ortiz-Ospina (2020), "The Selection of Talent: Experimental and Structural Evidence from Ethiopia", manuscript, University of Bristol.

Abel, M, R Burger, and P Piraino (2020), “The Value of Reference Letters: Experimental Evidence from South Africa”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, forthcoming.

Altonji, J and C Pierret (2001), “Employer Learning and Statistical Discrimination”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 116: 313–335.

Arcidiacono, P, P Bayer, and A Hizmo (2010), “Beyond Signaling and Human Capital: Education and the Revelation of Ability”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 2: 76–104.

Bassi, V and A Nansamba (2020), Screening and Signaling Non-Cognitive Skills: Experimental Evidence from Uganda, Working paper, University of Southern California.

Belot, M, P Kircher, and P Muller (2018), “Providing Advice to Jobseekers at Low Cost: An Experimental Study on Online Advice”, Review of Economic Studies 86: 1411–1447.

Bryan, G, S Choudhury, and A M Mobarak (2014), “Under-Investment in a Profitable Technology: The case of Seasonal Migration in Bangladesh”, Econometrica 82: 1671-1748.

Card, D, J Kluve, and A Weber (2018), “What Works? A Meta-Analysis of Recent Active Labor Market Program Evaluations”, Journal of the European Economic Association 16: 894–931.

Carranza, E, R Garlick, K Orkin, and N Rankin (2020), "Job Search and Hiring with Two-Sided Limited Information about Workseekers' Skills", Policy Research Working Paper 9345; Impact Evaluation Series, Washington DC: World Bank Group.

Conlon, J, L Pilossoph, M Wiswall, and B Zafar (2018), “Labor Market Search with Imperfect Information and Learning”, NBER Working paper 24988.

Franklin, S (2017), “Location, Search Costs and Youth Unemployment: Experimental Evidence from Transport Subsidies”, The Economic Journal 128: 2353-2379.

ILOSTAT (2019), Unemployment Statistics, International Labor Organization.

International Labor Organization (2020a), Global Employment Trends for Youth: Technology and the Future of Jobs, Geneva: International Labor Office.

International Labor Organization (2020b), Youth & COVID-19: Impacts on jobs, education, rights and mental well-being, Geneva: International Labor Office.

Kahn, L and F Lange (2014), “Employer Learning, Productivity, and the Earnings Distribution: Evidence from Performance Measures”, Review of Economic Studies, 84, 1575–1613.

Pallais, A (2014), “Inefficient Hiring in Entry-Level Labor Markets”, American Economic Review, 104, 3565–3599.

Pritchett, L (2013), The Rebirth of Education: Schooling Ain’t Learning, Washington, DC: Center for Global Development.

Ranchhod, V and R Daniels. (2020), Labor Market Dynamics in South Africa in the Time of COVID-19: Evidence from Wave 1 of the NIDS-CRAM Survey, Working paper, University of Cape Town.