Prisons are meant to deter crime and rehabilitate inmates. Evidence from Colombia suggests that in some circumstances prisons actually foster rather than prevent crime.

Every day, prisons around the world release tens of thousands of offenders. A key purpose of incarceration is to discourage offenders who face prison from continuing their criminal behaviour, a concept known as 'specific deterrence.' This differs from 'general deterrence,' that describes how the threat of punishment affects the broader population. Another important function of incarceration is to enhance human capital through prison-based rehabilitation programmes (Becker 1968, Ehrlich 1973). However, global recidivism rates are dramatically high. For instance, two-year reconviction rates in North America and Europe are in the 20-60% range, and these are clearly underestimates (Fazel and Wolf 2015).

There is a body of research about these mechanisms: specific deterrence (e.g. Rose and Shem-Tov 2021), rehabilitation (e.g. Bhuller et al. 2020), incapacitation (e.g. Buonanno and Raphael 2013), and general deterrence (e.g. Katz et al. 2003). Most of these studies, however, focus on average effects rather than specific groups of inmates. Two somewhat unexplored groups are specialised offenders with high levels of criminal skills and unskilled offenders exposed to negative peer influences. Do traditional mechanisms have the same effect on these populations?

In recent research (Escobar et al. 2023), we take a novel approach to study the production and persistence of criminal skills. By examining all incarceration periods and violent and non-violent property crime reports in Colombia, we find that property crime reports are higher around prisons on the days that inmates are released. We provide new perspectives on this issue.

The prison system in Colombia

The Colombian prison system, managed by the National Prison Institute under the Ministry of Justice, is centralised and comprises 138 facilities housing around 125,000 inmates as of late 2019. These prisons are distributed across 126 cities, with an average of 940 inmates per facility despite an average capacity of just 604. This results in a system-wide occupancy rate of 156%. Only two of the 138 prisons are not overcrowded, while 37 have more than twice as many inmates as they are designed to hold. In some prisons, there are as many as four or five inmates per slot, with the average occupancy rate reaching 182%.

Patterns of criminality in Colombia

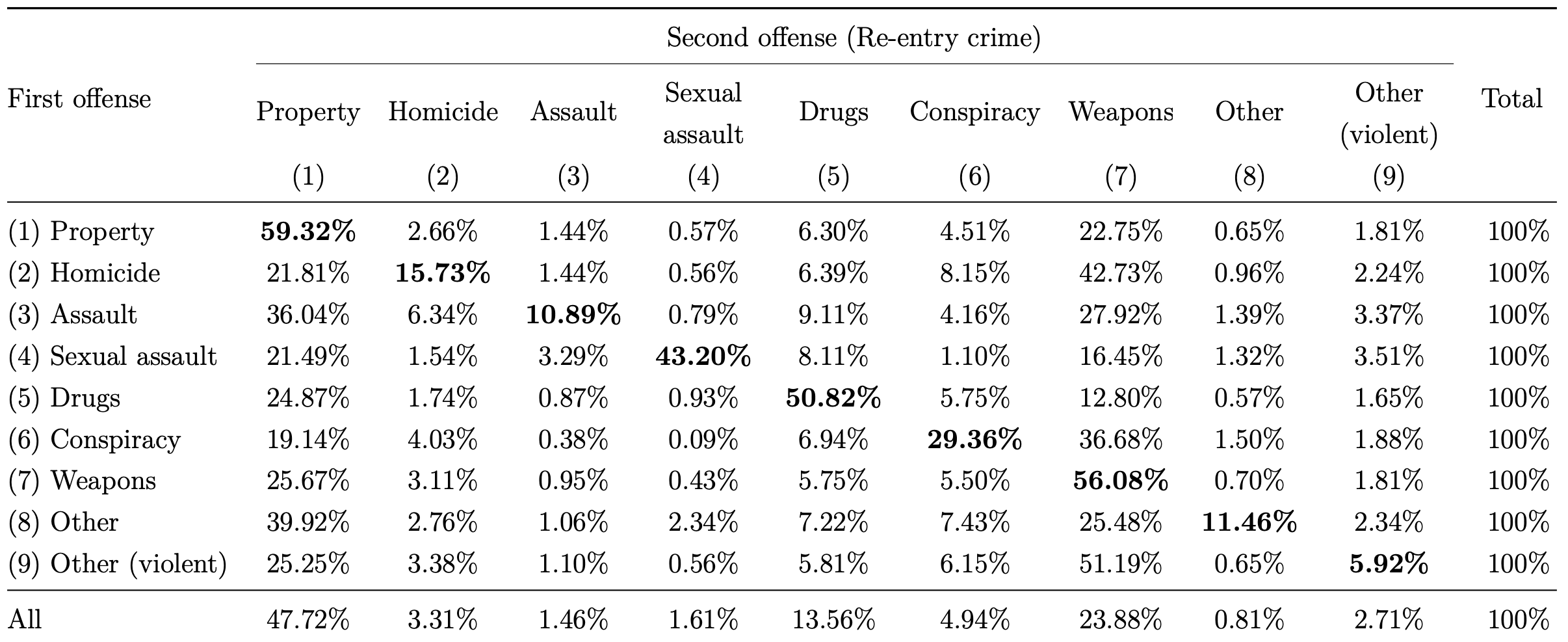

Offenders in Colombia show consistent patterns of specialisation and persistence in their criminal activities. Generally, most inmates tend to commit the same crime when they reoffend. Table 1 presents transition matrices detailing the type of crime committed during the first and second offenses for those convicted at least twice. This trend is particularly evident among those specialising in property crimes, with approximately 60% of property crime recidivists repeating the same offense. Similar patterns are observed in other categories, such as drug-related crimes and illegal possession of weapons and firearms, where over half of repeat offenders reoffend with the same crime.

Table 1. Transition matrices on first and second crime

Notes: The table presents the transition matrices for one year recidivism. We use our sample of all incarceration events in the 138 active prisons since January 2013 through September 2016. The column header corresponds to the numeration of the row labels. The diagonal of the matrix depicts the share of inmates who recidivate in the same type of crime.

Colombian law mandates that inmates be assigned to different prison wings based on gender, age, type of crime, personality traits, criminal records, and physical and mental health conditions. However, due to severe overcrowding in nearly all prisons, assignments are often made using ad hoc rules that help the National Prison Institute manage the challenges of overcrowding. For example, as two regional directors of the National Prison Institute reported during interviews in 2017, prison authorities typically rotate the prisons to which they send inmates. Within each prison, they rotate the specific wing where each inmate is placed. High-profile individuals may be exceptions to these practices, but they represent only a small fraction of the tens of thousands of inmates. As a result of these institutional constraints, offenders with diverse characteristics and backgrounds are frequently grouped across prison wings.

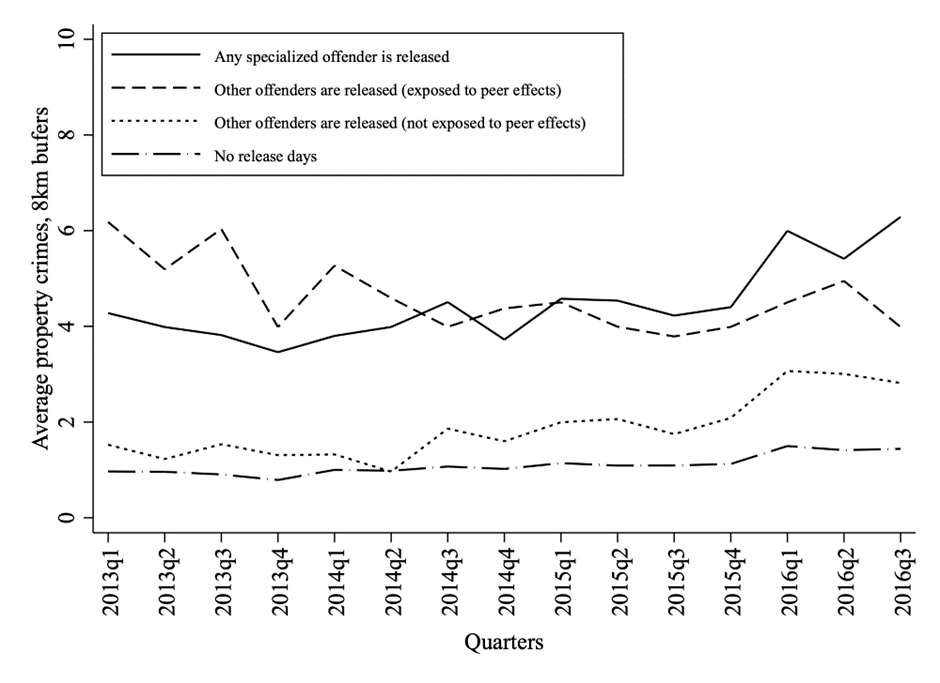

What happens when inmates are mixed in that way? Figure 1 provides some stylised facts. The figure illustrates the average number of reported property crimes per quarter within 8 km buffers around all prisons in our sample. The four lines on the graph represent different types of days: i) days when inmates specialised in property crimes are released, ii) days when inmates exposed to peer effects but not specialised in property crimes are released, iii) days when other inmates are released, and iv) days when no inmates are released. The data shows that crime rates are highest on days when specialised inmates or those influenced by peer effects are released.

Figure 1. Property crimes around prisons

The causal impacts of criminal skills production on first-day recidivism

To estimate the causal impact of inmate releases on crime near prisons, we follow a difference-in-difference approach by comparing days with and without offender releases. Within an 8 km radius, we observe an additional 0.17 reported property crimes on release days, indicating that crime reports are approximately 15% higher. Our results also suggest that two types of inmates drive these impacts: property crime specialists—inmates with a prior conviction for violent or non-violent theft; and trainees—non-specialised inmates who interacted heavily with property crime specialists during incarceration.

To further explore the development and persistence of criminal skills, we examine whether participation in rehabilitation programmes—which theoretically enhance non-criminal human capital—or longer incarceration spells mitigate these adverse effects. We observe no evidence of such mitigation.

A few policy implications on improving prisons

Our findings suggest that the deterrent effect of incarceration may be weak for highly skilled offenders. At the same time, prisons tend to have criminogenic - rather than deterrent - effects on unskilled offenders who are exposed to intense peer influences. We also considered whether participation in rehabilitation programmes or longer prison sentences reduces the likelihood of reoffending among inmates who either have a specialised criminal profile or are unskilled but frequently interact with more specialised offenders.

Establishing an effective prison system is costly for taxpayers. For example, annual corrections expenditures in the US total about $80 billion, or $35,000 per inmate, representing 20% of the total justice system expenditures. In Colombia, annual spending on corrections amounts to $1.9 billion, or $15,000 per inmate. Therefore, from a policy standpoint, ensuring that the prison systems work as intended is crucial, and our research raises concerns about whether and how prisons can achieve broader societal goals.

References

Becker, G S (1968), “Crime and punishment: An economic approach,” Journal of Political Economy, 76(2): 169-217.

Bhuller, M, G B Dahl, K V Løken, and M Mogstad (2020), “Incarceration, recidivism, and employment,” Journal of Political Economy, 128(4): 1269-1324.

Buonanno, P, and S Raphael (2013), “Incarceration and incapacitation: Evidence from the 2006 Italian collective pardon,” American Economic Review, 103(6): 2437-2465.

Ehrlich, I (1973), “Participation in illegitimate activities: A theoretical and empirical investigation,” Journal of Political Economy, 81(3): 521-565.

Escobar, M A, S Tobón, and M Vanegas-Arias (2023), “Production and persistence of criminal skills: Evidence from a high-crime context,” Journal of Development Economics, 160: 102969.

Fazel, S, and A Wolf (2015), “A systematic review of criminal recidivism rates worldwide: Current difficulties and recommendations for best practice,” PLoS One, 10(6): e0130390.

Katz, L, S D Levitt, and E Shustorovich (2003), “Prison conditions, capital punishment, and deterrence,” American Law and Economics Review, 5(2): 318-343.

Rose, E K, and Y Shem-Tov (2021), “How does incarceration affect reoffending? Estimating the dose-response function,” Journal of Political Economy, 129(12): 3302-3356.