A prison construction programme in Colombia aimed at improving prison conditions reduced recidivism of released offenders and was a net benefit to society

One of very few policies adopted almost universally throughout history is the use of incarceration as a form of punishment for offenders. Today, more than 11 million people are incarcerated worldwide (Fair and Walmsley 2021). One key role of incarceration is to prevent offenders who served time from re-engaging in criminal behavior. In theory, this should be the result of a specific deterrence effect induced by the threat of additional punishment and better skills achieved through resocialisation programmes (Becker 1968, Ehrlich 1973). Despite this, recidivism rates remain stubbornly high. For instance, re-conviction rates over a two-year period range from 20% to 60% in North America and Europe (Fazel and Wolf 2015).

Although studies on prisons are common across social sciences, one aspect of incarceration that has received less academic attention is the role of prison conditions. Human rights considerations aside, if prisons offer few or no services to inmates, the specific deterrence effect could potentially be stronger. Nonetheless, there could be countervailing forces. For instance, inmates’ abilities to engage in legal work might diminish and their abilities to participate in criminal enterprises could improve. Prison conditions become even more important as the demand for prison space grows faster than supply. For instance, the incarceration rates per 100,000 residents in Latin America and Southeast Asia increased from 133 to 259 and from 100 to 171, respectively, between 2000 and 2018. Prison construction processes are slower, hence the average occupancy level of prisons in these regions has increased steadily (Fair and Walmsley 2021).

In a recently published article (Tobón 2022), I study the effects of prison conditions on recidivism by analysing a prison construction programme in Colombia that aimed to improve prison quality with newer, less crowded, and higher-service prisons.

Background, context, and stylized facts

The prison system in Colombia is centralised and managed by the National Prison Institute. Currently, the system has about 120,000 inmates distributed across 137 prisons and temporary detention centers. Because of the systematic violation of constitutional rights to the prison population, the Colombian Constitutional Court has formally declared an unconstitutional state of affairs on several occasions. These declarations are intended to demand immediate action from all branches of the state to address the situation and protect the inmates’ rights.

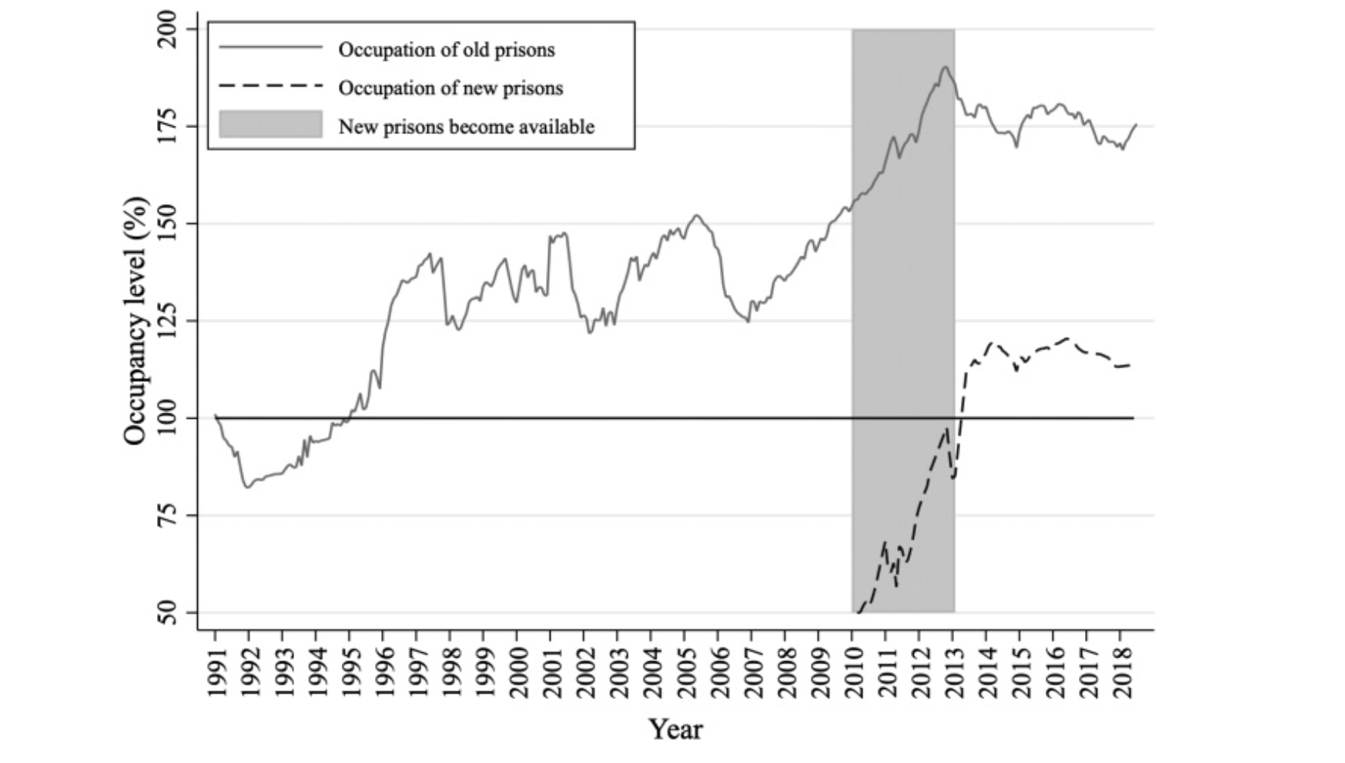

One of the actions the government took as a response to these declarations was to commission the construction of new prisons in 2004. After a relatively long process, ten new prisons opened between 2010 and 2013. While the opening of these new prisons coincided with a generalised burst in prison population because of more punitive legislation, broadly, occupancy levels and conditions were much better in the new versus the old prisons. The evolution of the occupancy levels for old and new Colombian prisons is depicted in Figure 1. By the end of the period, occupancy levels in old prisons averaged about 1.75 inmates per slot, while occupancy levels in new prisons averaged about 1.2 inmates per slot. Furthermore, official data shows that new prisons not only have more space, but also higher expenditures per inmate, a stronger supply of resocialisation programs, and fewer claims of rights violations per inmate.

Figure 1: Occupancy levels for old and new Colombian prisons

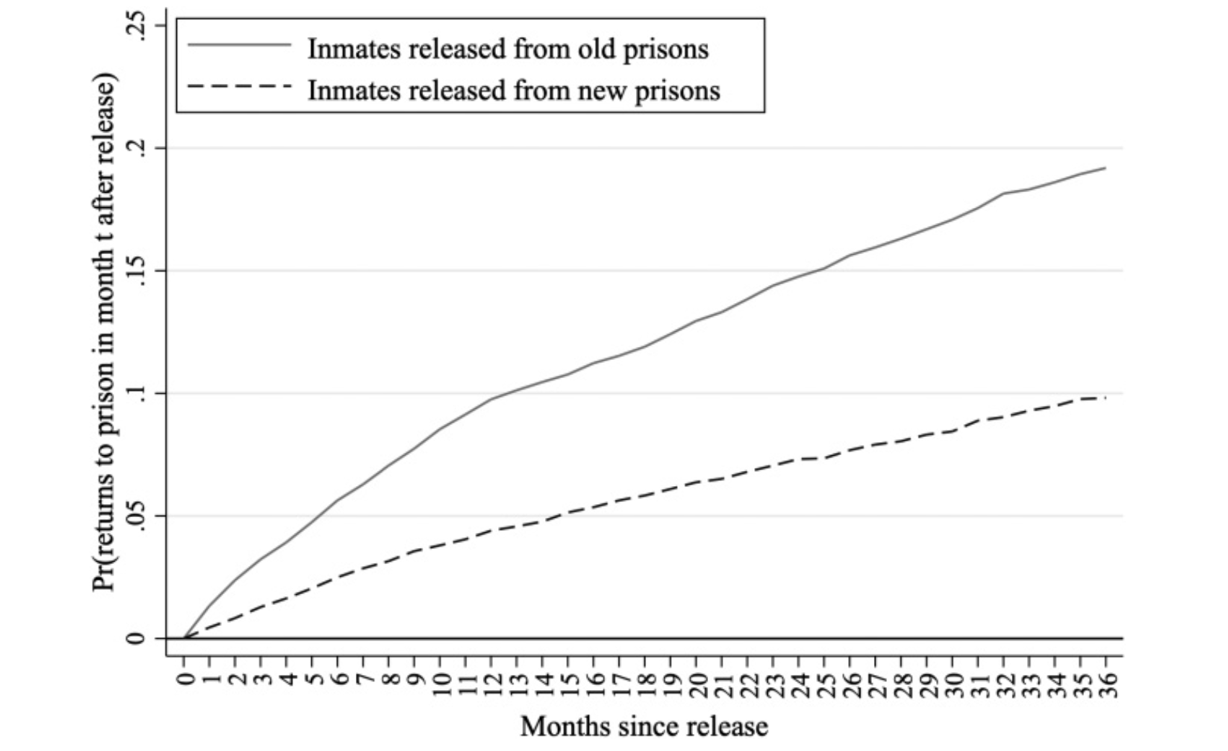

Descriptively, the data suggests the patterns of re-incarceration are rather different for inmates exiting from new versus old prisons. Figure 2 presents the probability of returning to prison after being released within a time period of one to 36 months. Three years after release, the probability of an inmate returning to the prison system is about 20% for offenders released from old prisons and 10% for offenders released from new prisons. I examine whether this is a causal relationship below.

Figure 2: Probability of returning to prison after being released

The causal impacts of prison conditions on recidivism

Estimating the impact of prison conditions is challenging because there might be unobservable inmate characteristics that influence assignment to new prisons and post-release criminal behavior. In Colombia, prison assignment occurs at the judicial district level and is determined by the National Prison Institute based on a series of demand and supply factors. For instance, convicted inmates should be placed where their families live, and high-risk inmates should be placed in high-risk prisons.

But because most inmates commit crimes where they live, most prisons have high-risk wings, and all judicial districts have more than one prison, with a few exceptional cases, there is always more than one prison available for each individual assignment. Hence, to prevent any individual prison from having heavy changes in the prison population, the National Prison Institute sends inmates in small sequences to one prison and then to another, arbitrarily, on a rotating basis. Consistent with the assignment procedure not being explained by individual inmate characteristics, the data suggests inmates assigned to new and old prisons are statistically indistinguishable in terms of their characteristics.

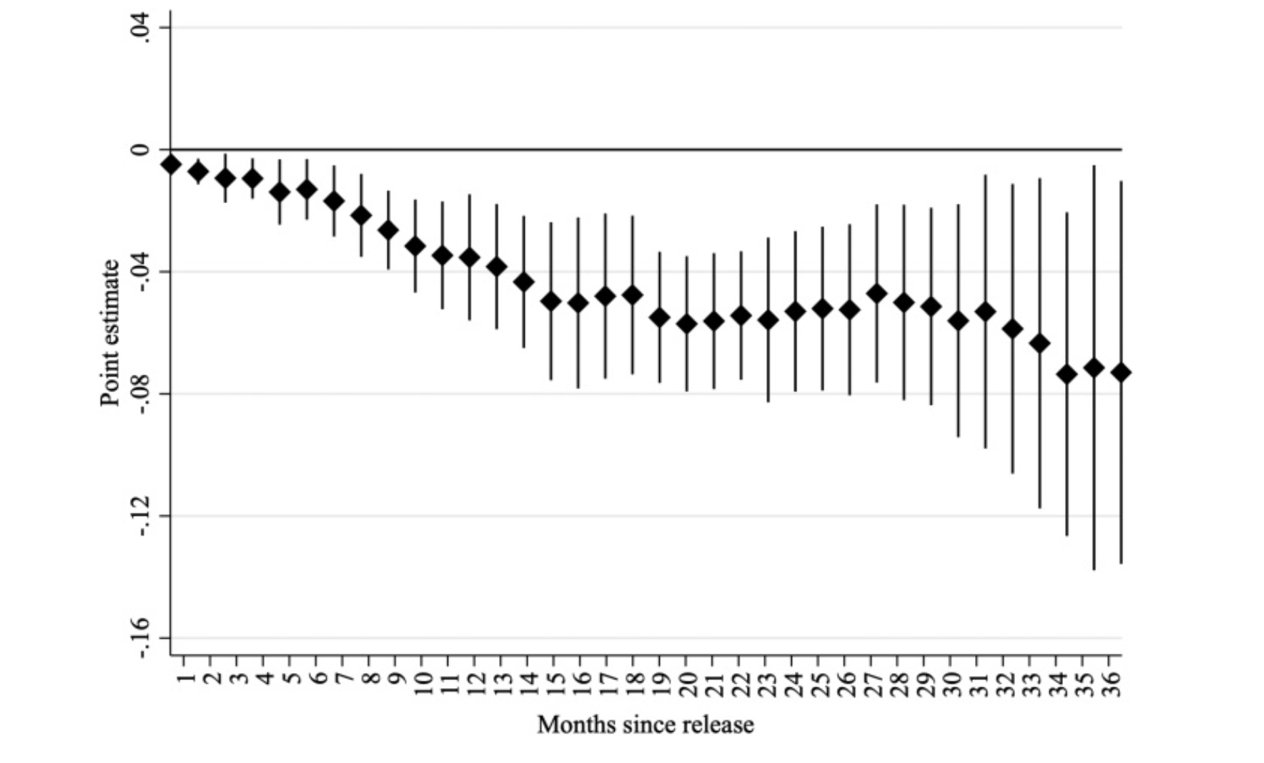

To estimate the impacts, I compare average reincarceration rates between inmates released from new versus old prisons, controlling for a variety of characteristics, such as demographic information, criminal profiles, and several unobserved potential traits such as local criminal or legal opportunities at the time of release. The main impacts for different time frames are in Figure 3. All the estimates suggest assignment to a new prison reduces the probability of recidivism. The magnitude of the coefficient, measured in percentage points, grows from about 0.5 in one month to 7.3 in 38 months. Relative to the corresponding averages for inmates sent to old prisons, the effects range between 35% and 38%. In an additional analysis to examine the underlying mechanisms, I find that inmates in new prisons have fewer opportunities to develop criminal skills and networks, more opportunities to engage in resocialisation programmes, and a better prison experience that could trigger beneficial changes in intrinsic preferences over illegal occupations.

Figure 3: The effect of prison conditions on recidivism for different time frames

How generalizable are these results?

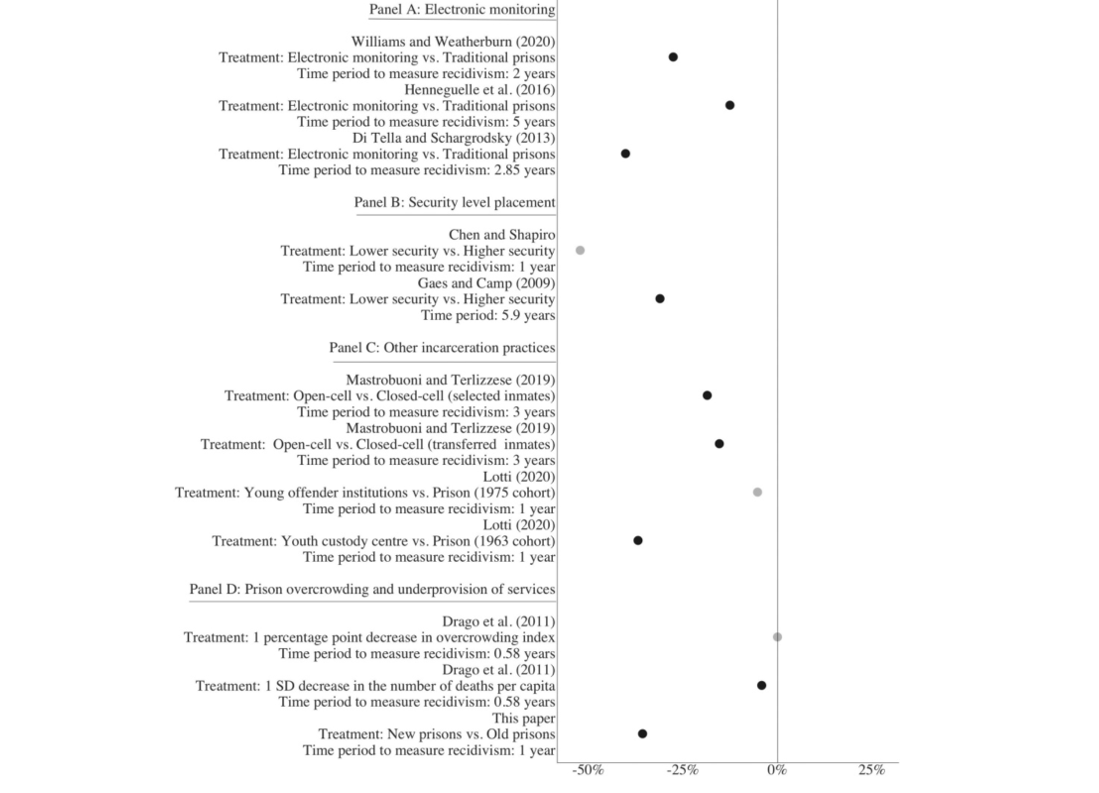

The question of external validity is always hard to address. Nonetheless, a review of studies focusing on different attributes of prison conditions proves revealing. Figure 4 presents the impacts of being assigned to better conditions on recidivism across all studies. Negative values favour the less harsh prison experience. These include research examining the impacts of electronic monitoring (Williams and Weatherburn 2020, Henneguelle et al. 2016, Di Tella and Schargrodsky 2013), security level placement (Chen and Shapiro 2007, Gaes and Camp 2009), other incarceration practices such as open cells (Matrobuoni and Terlizzese 2019, Lotti 2020), and prison overcrowding and underprovision of services (Drago et al. 2011, Tobon 2022).

While directly comparing magnitudes is not useful to the extent that studies vary along many dimensions, including the type of intervention and the time frames to measure recidivism, Figure 4 reveals a clear pattern: Along virtually all analyses, assigning inmates to improved conditions of any form reduces the risk of recidivism.

Figure 4: Comparison to other studies

A few policy implications

Overall, these findings suggest providing better prison conditions to inmates potentially improves security by reducing recidivism and interrupting criminal careers—or preventing offenders from developing them. The first way to achieve this goal is what Colombia did starting in 2004: Building new prisons. Indeed, in a back-of-the-envelope welfare analysis, I find that this massive construction programme most likely created more social returns than its aggregate economic cost.

A second alternative that might be more cost-effective is decarceration. Many inmates who are in prison were convicted for crimes that are not particularly costly to society. In Colombia, for example, about 15% of the prison population was convicted for carrying small amounts of soft drugs such as marijuana. Because better prison conditions improve post-release outcomes for inmates, by releasing the least harmful inmates those who remain in prison would benefit. Relatedly, a more expedited judicial system could contribute to the decarceration process by ensuring that on-trial inmates face trial quickly and that inmates who can access early release or parole do it on time.

A final alternative is to improve services within prisons. The spectrum includes a wide range of options, such as providing services that limit the development of criminal skills and networks, improving marketable skills and education, and broadly allowing inmates to have a better prison experience.

References

Becker, G (1968), “Crime and Punishment: An Economic Approach,” Journal of Political Economy 76(2): 169–217.

Chen, M K, and J M Shapiro (2007), “Do Harsher Prison Conditions Reduce Recidivism? A Discontinuity-Based Approach,” American Law and Economics Review 9(1): 1–29.

Di Tella R, and E Schargrodsky (2013), “Criminal Recidivism after Prison and Electronic Monitoring,” Journal of Political Economy 121(1): 28–73.

Drago, F, R Galbiati, and P Vertova, (2009) “The Deterrent Effects of Prison: Evidence from a Natural Experiment,” Journal of Political Economy 117(1): 257–280.

Ehrlich, I, (1973) “Participation in Illegitimate Activities: A Theoretical and Empirical Investigation,” Journal of Political Economy 81(3): 521

Fair, H, and R Walmsley (2021), World Prison Population List, 12th ed. (London: Institute for

Criminal Policy Research)

Fazel, S, A Wolf (2015), “A systematic review of criminal recidivism rates worldwide:

Current difficulties and recommendations for best practice.” PLoS One 10(6): e0130390.

Gaes, G G, and S D Camp, (2009), “Unintended Consequences: Experimental Evidence for the Criminogenic Effect of Prison Security Level Placement on Post-Release Recidivism,” Journal of Experimental Criminology 5(2): 139–162.

Henneguelle, A, B Monnery, and A Kensey (2016), “Better at Home Than in Prison? The Effects of Electronic Monitoring versus Incarceration on Recidivism in France,” Journal of Law and Economics 59(3): 629–667.

Lotti, G (2020), “Tough on Young Offenders: Harmful or Helpful?” Journal of Human Resources 57(4): 1017–9113.

Mastrobuoni, G, and D Terlizzese (2022), “Leave the Door Open? Prison Conditions and Recidivism” AEJ: Applied Economics 14(4): 200-223

Tobón, S (2022), “Do better prisons reduce recidivism? Evidence from a prison construction program.” Review of Economics and Statistics 104(6): 1256–1272

Williams, J, and D Weatherburn (2020), “Can Electronic Monitoring Reduce Reoffending?” Review of Economics and Statistics 104(2): 1–46.