Enhanced tax administration can increase government revenue collection from medium-sized firms in developing countries even more than raising tax rates

The ability to raise tax revenue is crucial for the functioning of any state. However, in many developing and emerging economies, tax revenue collection remains low: while high-income countries typically collect around 40% of their GDP in tax revenue, low-income countries collect only between 10 and 20%.

Some of the barriers to tax revenue collection in developing countries come from the unique structural features of their economies – informal labour markets, small firms, and limited banking systems – which make it challenging for authorities to observe and tax economic transactions (Gordon 2009, Kleven 2016, Jensen 2019). Given these challenges, one view is that merely raising tax rates to increase revenue will be ineffective unless governments first invest in improving administrative tax capacity (Besley 2014).

Studying enhanced tax administration

In a recent study (Basri et al. 2020), we explore whether large-scale administrative reforms can boost tax revenue collection. In the mid-2000s, Indonesia re-organised its tax administration structure such that the largest several hundred corporate taxpayers in each of its main tax regions were moved to special ‘Medium Size Taxpayer Offices’ (MTOs), one for each region.

Firms in these MTOs were treated exactly the same as those handled by regular tax offices, with one key difference: in regular tax offices, each staff member or ‘account representative’ was responsible for providing assistance to and monitoring 56 to 125 firms, as well as many thousands of individual tax payers. In the MTOs, on the other hand, each account representative worked only with around 12 to 26 corporate taxpayers and no individual taxpayers. Firms in the MTO would thus be able to get more help from tax officers, but would also be monitored more closely.

To analyse the impact of being assigned to the MTO, we compared the difference in outcomes between similar firms assigned either to MTOs or regular tax offices, both before and after assignment (of the relevant firms) to the MTOs. We confirmed that prior to moving to the MTO, the firms looked similar along many characteristics, and were growing at similar rates in terms of gross income and tax revenue. Thus, any differences in outcomes could be attributed solely to the enhanced tax administration they received in the MTO.

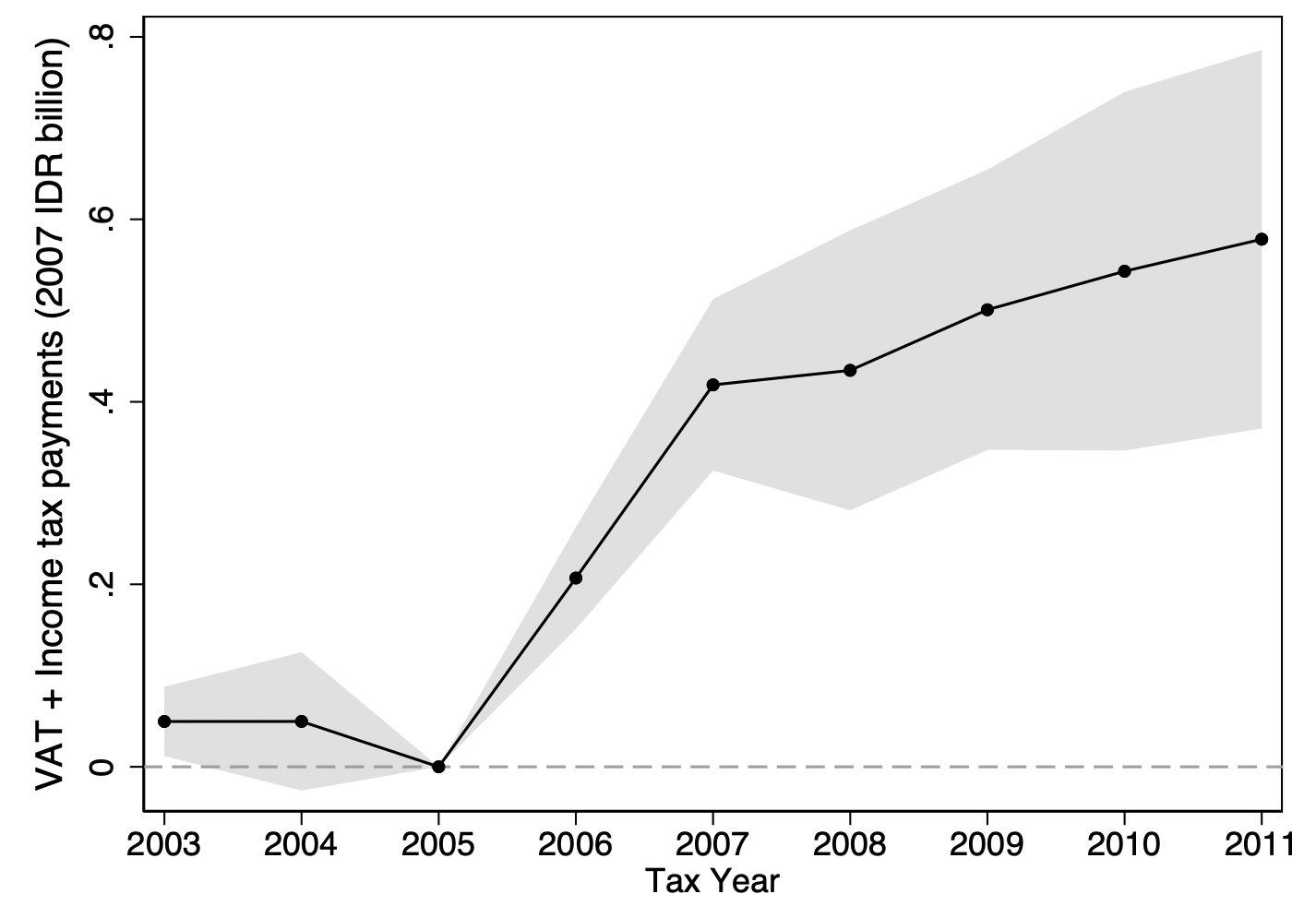

The study found that MTOs dramatically increased tax revenue at a very low cost to the government. As shown in Figure 1, the real total taxes paid in the MTO increased by 340 million Indonesian rupiah (IDR) on average – a 128% increase relative to what would have happened if they were not assigned to an MTO. In contrast, the increased costs of the administrative reform (the cost of running the MTOs) was tiny, at less than 1% of the additional revenue collected. Hence, the benefits of the reform far outweighed its costs. In fact, on net, the estimated net revenue return from enhanced tax administration, which covered just 4% of all firms, amounts to a lower-bound total effect of IDR 40 trillion (US$4 billion at the 2007 exchange rates).

Figure 1 Effect of MTO on total taxes paid

A concern around these findings can be that improved administration can increase tax revenue at first, but only till firms figure out ways to evade taxes again. However, we found evidence of the opposite being true: MTO effects actually grow over time. The effects of MTOs on taxes paid and on reported gross incomes six years after firms were assigned to the MTO were about 1.5 to 2.5 times larger than they were two years after their being moved to the MTO, despite the fact that staffing levels at and enforcement actions from the MTO remained essentially constant over this time period.

What are the mechanisms around the reform?

Analysing the mechanisms behind the firms’ reactions to the MTO can help us better understand how administrative reforms can generally work. First, there is a question of whether MTOs have the effect of helping formalise transactions (i.e. bringing previously hidden transactions on the books) or leading to greater scrutiny of deductions or simply improving the collection of tax arrears. We find that the creation of the MTOs led to an increase in reported revenues, reported costs, reported number of permanent employees, and a higher reported wage bill. Reported costs, revenues, and taxable income all increase at roughly similar rates at the MTO, with no impact on reported profit margins or collections as a share of taxes due. This suggests that the MTO may have led to more business being formally reported to the tax authority.

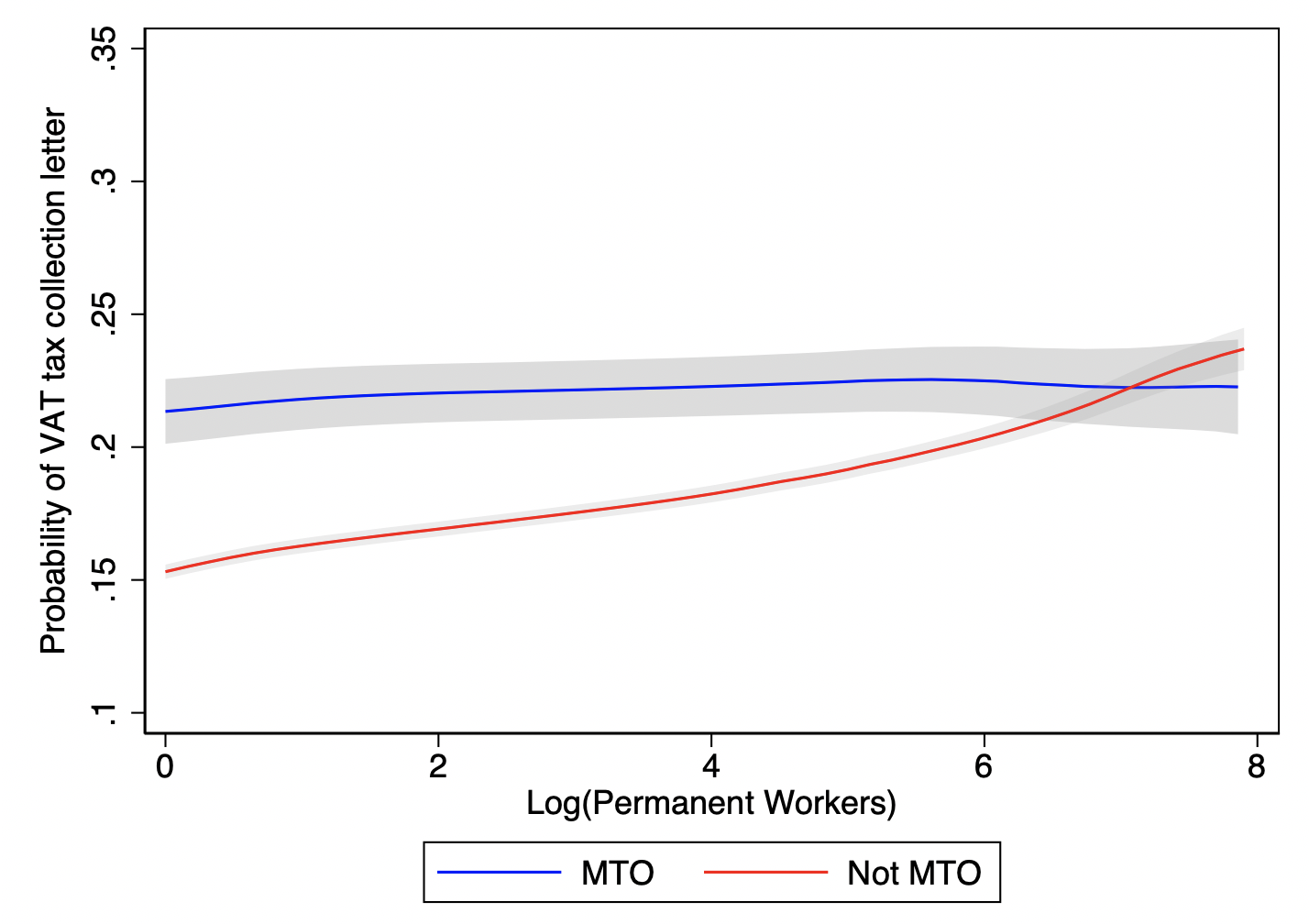

Second, we explored whether MTOs alleviated barriers to firm growth through a reduction in size-dependent enforcement. As shown in Figure 2, we find that in the regular tax offices, enforcement (e.g. formal letters for late payment and audits) increases as firms get larger. This makes sense since with limited time and lots of taxpayers to handle, account representatives at regular tax offices would want to devote more effort to taxpayers who would yield the highest revenue returns. However, in the MTO, we found that the tax officials pay equal attention to firms regardless of size, since they handle fewer firms. This difference in size-based enforcement could be one reason why firms in the MTO have higher reported gross income and permanent employment over time, as they would no longer be ‘penalised’ for reporting higher figures or growth.

Figure 2 Post-MTO assignment tax assessment as a function of firm size

Improved administration vs tax rate change

Improving tax administration is one way that governments could aim to increase tax revenue. Another path is to directly increase the tax rate. Which policy would yield higher returns?

Indonesia had a series of tax reforms in 2009 and 2010 that differentially changed the tax rates on firms. We studied these reforms to understand the elasticity of taxable income for firms: the actual increase in government revenue due to an increase in the tax rate. We estimate an elasticity of taxable income of 0.59. Using this figure, we calculated that the revenue maximising tax rate for Indonesia is 56%, which is much higher than the 30% top marginal tax rate.

This means that the government can raise greater revenue by raising the statutory tax rate if it wants to. But raising revenues through tax rates does not come without a cost; our elasticity of taxable income estimate also implies the marginal excess burden for taxpayers is 0.51. In other words, each dollar of taxes raised through the increased tax rate imposes an additional burden of 0.51 cents on taxpayers. Those 0.51 cents are pure deadweight loss: neither taxpayers nor the government gets to keep them.

Putting this together, we can compare an improvement in tax administration with a change in the tax rate. Specifically, how much would marginal corporate income tax rates have to be increased to raise the same amount of revenue that the government obtained by improving tax administration? The answer is substantial. To obtain the increase in corporate income taxes paid by MTO taxpayers alone, the top marginal corporate income tax rates on all firms would have had to be raised by eight percentage points (from 30% to 38%).

Policy implications

The findings from our study have large implications for policy. We show that developing country governments can increase tax revenue through both enhanced administration and increases in tax rates. But they also imply, at least in the case of medium-sized firms, that improving administration can have a particularly dramatic effect in increasing revenues.

References

Basri, M C, M Felix, R Hanna and B A Olken (2020), “Tax Administration vs. Tax Rates: Evidence from Corporate Taxation in Indonesia”, Working Paper.

Gordon, R and W Li (2009), “Tax structures in developing countries: Many puzzles and a possible explanation”, Journal of Public Economics 93: 855–866.

Jensen, A (2019), “Employment Structure and the Rise of the Modern Tax system”, NBER Working Paper 25502.

Kleven, H J, C T Kreiner and E Saez (2016), “Why can modern governments tax so much? An agency model of firms as fiscal intermediaries”, Economica 83: 219–246.

Besley, T and T Persson (2014), “Why do developing countries tax so little?”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 28: 99–120.