A large-scale debit card rollout to cash transfer recipients in Mexico led small retailers to adopt point-of-sale terminals and had a broad range of impacts on financial technology adoption, shopping behaviour, and retailer sales and profits.

The rapid spread of payment technologies—including debit cards, mobile money, and fast payment systems—is transforming how people shop, save, and borrow in developing countries. These technologies can significantly reduce transaction costs and improve financial inclusion (Jack and Suri 2014, Suri et al. 2023). However, the adoption of these technologies can be held back by coordination failures in two-sided markets: consumers won’t adopt if retailers don’t accept the technology, and vice versa. This creates a chicken-and-egg problem that can trap an economy in a low-adoption state (Katz and Shapiro 1986).

Higgins (forthcoming) examines how a large government programme in Mexico overcame this barrier by distributing about one million debit cards to recipients of its Prospera conditional cash transfer programme. This created a coordinated shock to consumer adoption of debit cards in local markets.

Using rich microdata on both sides of the retail payments market, I trace out how this consumer shock filtered through to retailer technology adoption, and then spilled over to affect other consumers’ debit card adoption and shopping patterns, as well as retailer sales and profits. The findings demonstrate the power of government policy to jump-start a virtuous cycle of financial technology adoption.

Two years after the debit cards were distributed, corner stores had increased point-of-sale (POS) terminal adoption by 18% compared to those in localities that received debit cards later. In turn, other consumers (non-Prospera recipients) increased debit card adoption by 28% and shifted spending from large to small retailers, who increased their sales by 6% and profits by 19%.

Financial technology adoption in Mexico

The percent of adults who do not have a debit card, credit card, or mobile money account in Mexico is high, at 71%—compared to 50% worldwide (Demirgüç-Kunt et al. 2018). The percent of the population with debit cards is also highly correlated with income: in urban areas in 2009 (prior to the Prospera debit card rollout), 12% of households in the bottom 20% of the income distribution had a debit card, compared to 54% of households with incomes in the top 20%.

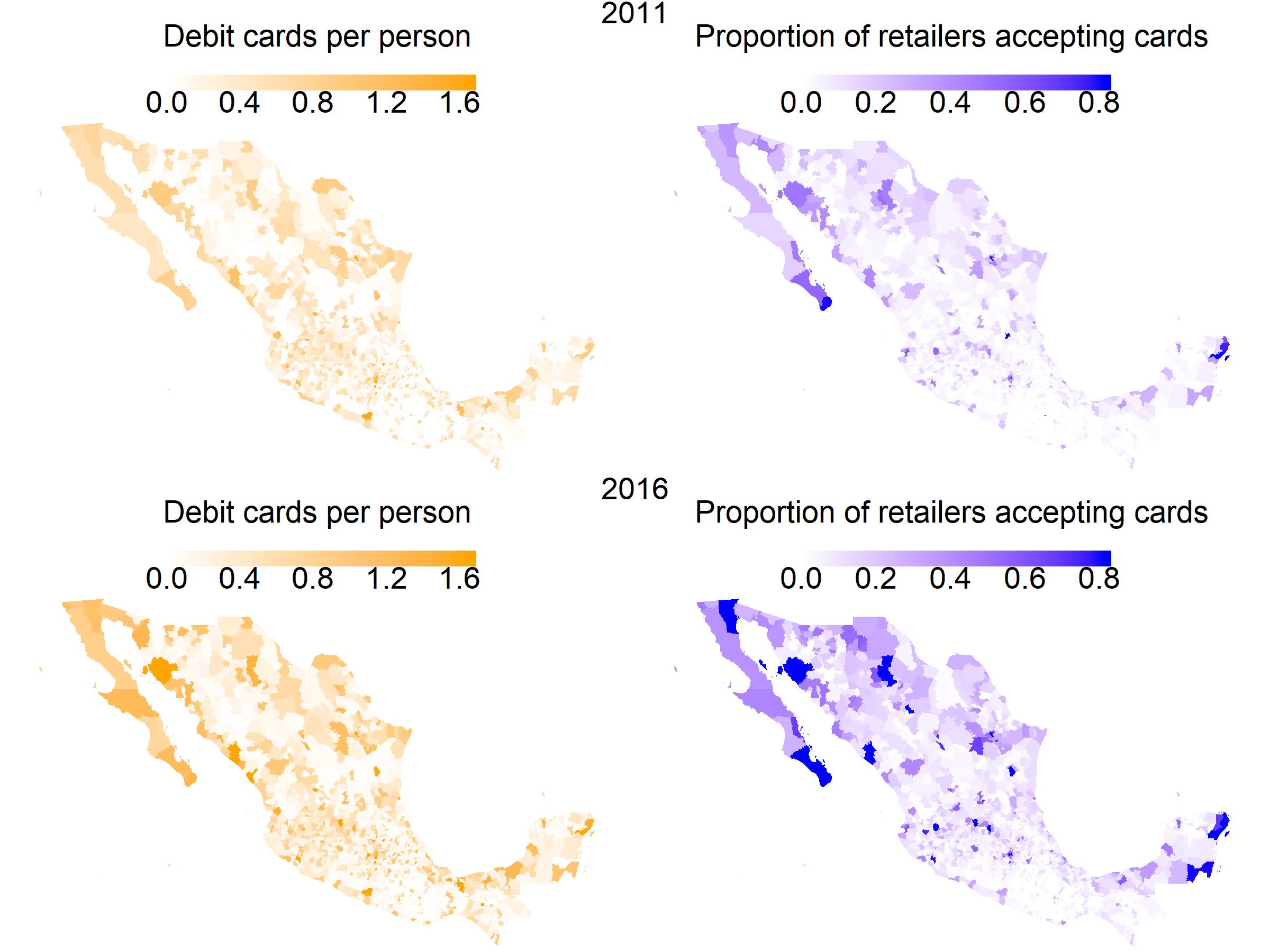

On the supply side of the market, 32% of retailers in urban areas had adopted POS terminals, including 26% of corner stores and nearly 100% of supermarkets. Descriptively, adoption on the two sides of the market is highly correlated: comparing the maps in Figure 1, it is clear that areas with high levels of debit card adoption tend to have high levels of POS terminal adoption, and that areas that had large increases in debit card adoption over time also had large increases in POS terminal adoption.

Figure 1. Adoption of debit cards and POS terminals over space and time

The debit card rollout aimed to reduce the high transaction costs of accessing cash transfers

The government’s Prospera programme (previously known as Progresa and Oportunidades) had already made significant strides in reducing poverty through conditional cash transfers (Gertler 2004, Parker and Vogl 2018). However, beneficiaries still faced high transaction costs to access their transfers, often having to travel long distances to bank branches (Bachas et al. 2018a, b).

The debit card rollout aimed to reduce these costs by allowing beneficiaries to withdraw cash from any ATM or make purchases directly at stores with POS terminals (Bachas et al. 2021). This large-scale intervention targeted to a subset of consumers provides a unique opportunity to study the dynamics of financial technology adoption in a two-sided market.

Corner stores responded by increasing POS terminal adoption, leading to spillover effects on non-Prospera consumers

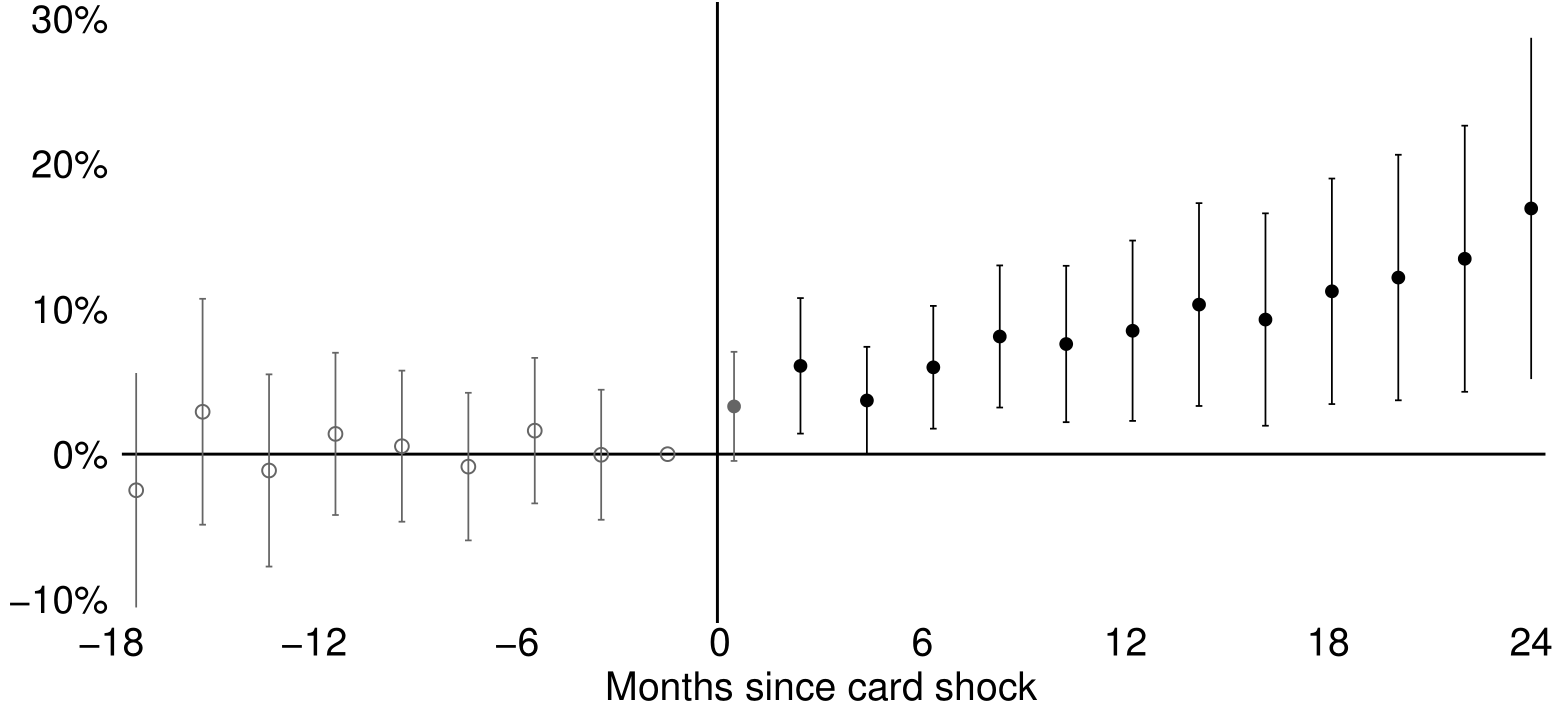

The debit card rollout had significant impacts on retailer technology adoption. In the first two months after the card rollout, the number of corner stores that had adopted POS terminals to accept card payments increased by 3% in treated areas compared to not-yet-treated areas, and by two years after the card rollout, corner store POS terminal adoption had increased by 18% (Figure 2). There was no effect on POS terminal adoption at supermarkets, which already had near-universal POS adoption.

Figure 2. Percent change in number of corner stores with POS terminals

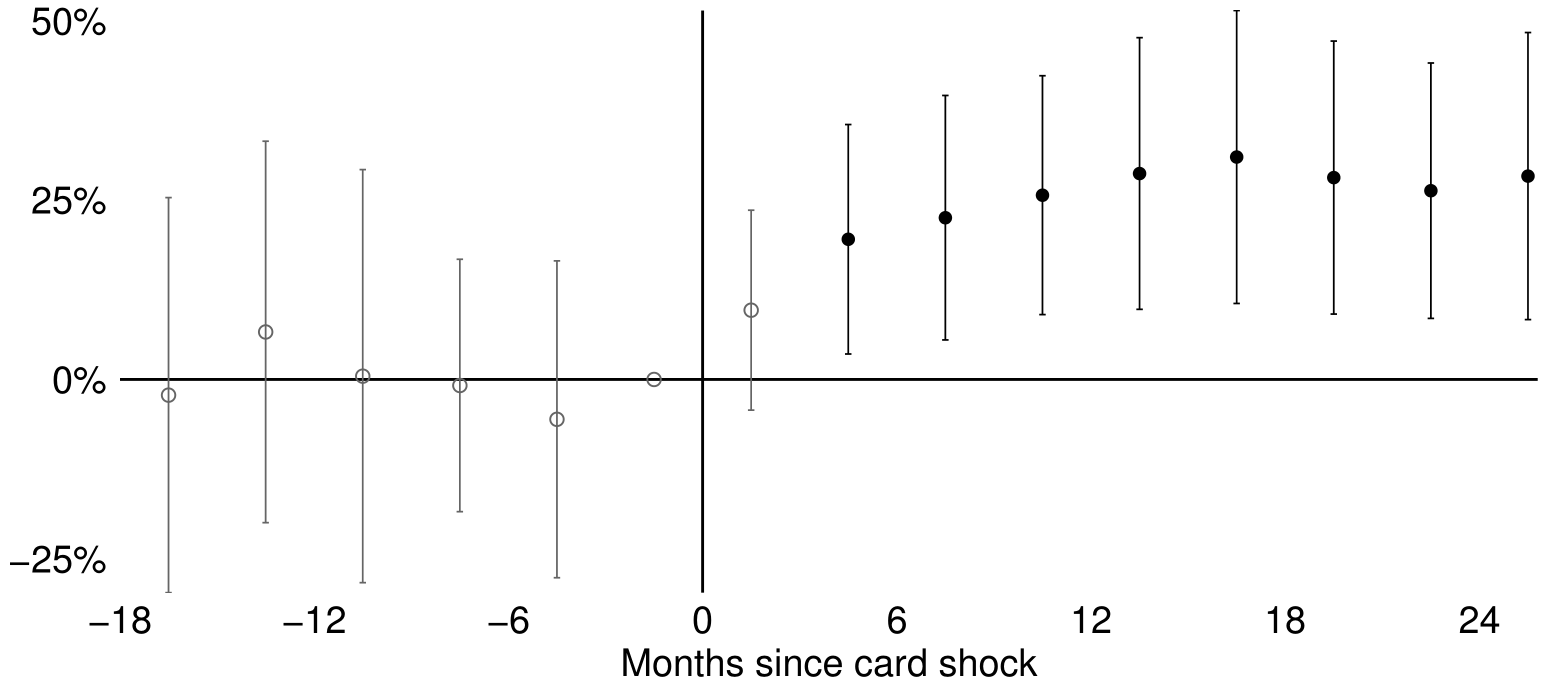

This increase in retailer POS terminal adoption then spilled over to affect other consumers beyond the original Prospera debit card recipients. Two years after the shock, the number of other consumers with debit cards increased by 28% in treated localities compared to not-yet-treated localities (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Percent change in number of other households with debit cards

The increased availability of electronic payments at corner stores also changed shopping patterns, particularly for higher-income consumers. Households in the top 20% of the income distribution shifted about 13% of their supermarket spending to corner stores after the shock. This was driven by making 0.8 more trips per week to corner stores and 0.2 fewer trips to supermarkets on average, once corner stores had adopted POS terminals to accept card payments.

Corner store sales and profits rose following POS terminal adoption

The shift in consumer spending benefitted small retailers at the expense of supermarkets. Corner store sales increased by 6% in early-treated localities relative to those treated later. Furthermore, corner stores increased the amount of inventory they bought and sold without increasing other input costs such as wages, number of employees, rent, capital, or utilities, which led to a 19% increase in their profits.

Meanwhile, supermarket sales decreased by 12%, with the magnitude of lost sales closely matching the gains to corner stores in aggregate. The shift from supermarkets to corner stores represents a redistribution towards smaller firms and less wealthy business owners, as corner store owners are more prevalent in the bottom 60% of the income distribution in Mexico, while supermarket owners are exclusively in the top 40%.

Evidence of a coordination failure

To test whether coordination failures were constraining financial technology adoption prior to the shock to debit card adoption, I conducted a survey with 1,760 corner store owners in 29 urban localities that were not included in the debit card rollout—but had similar levels of debit card and POS terminal adoption as those included had just before receiving debit cards. When asked how adopting a POS terminal would affect their profits, 89% of corner store owners without POS terminals predicted a smaller profit change than what was observed in rollout localities.

This is evidence of a coordination failure: in the absence of a shock to debit card adoption, the vast majority of corner store owners in the survey thought that their change in profits would be lower than the actual treatment effect of the debit card shock on profits. This is likely due to a combination of two factors:

- The benefits of POS adoption are sufficiently high only after more consumers have adopted debit cards.

- Owners underestimate the benefits of adoption.

The survey results suggest that corner store owners do underestimate how many new customers would come to the store if they adopted: only 28% of corner store owners without a POS terminal thought that the number of customers coming to their store would increase after adopting, whereas 51% of corner store owners with POS terminals reported that their number of customers increased after adopting.

Policy implications for financial inclusion and technology adoption

The findings demonstrate how government policy to spur adoption on one side of a two-sided market can overcome coordination failures and lead to a virtuous cycle of adoption on the demand and supply sides of the market. While the Mexican government’s primary goal was reducing recipients’ travel costs to access transfers, the programme had much broader impacts on financial technology adoption, shopping behaviour, and retailer sales and profits.

More broadly, the results suggest that efforts by governments and NGOs to foster financial inclusion among the poor through technologies like debit cards and mobile money may have significant positive spillovers. By coordinating adoption among a subset of consumers, such programmes can jump-start network effects that catalyse broader adoption of financial technologies and benefit the broader population and local businesses.

References

Bachas, P, P Gertler, S Higgins, and E Seira (2018a), “Digital Financial Services Go a Long Way: Evidence from Mexico,” American Economic Association Papers & Proceedings, 108: 444-448.

Bachas, P, P Gertler, S Higgins, and E Seira (2018b), “Digital Financial Services Go a Long Way: Evidence from Mexico,” VoxDev. https://voxdev.org/topic/finance/digital-financial-services-go-long-way-evidence-mexico.

Bachas, P, P Gertler, S Higgins, and E Seira (2021), “How Debit Cards Enable the Poor to Save More,” Journal of Finance, 76(4): 1913-1957.

Demirgüç-Kunt, A, L Klapper, D Singer, and S Ansar (2018), The Global Findex Database 2017: Measuring Financial Inclusion and the Fintech Revolution, World Bank Publications.

Gertler, P (2004), “Do Conditional Cash Transfers Improve Child Health? Evidence from PROGRESA’s Control Randomized Experiment,” American Economic Review, 94(2): 336-341.

Higgins, S (forthcoming), “Financial Technology Adoption: Network Externalities of Cashless Payments in Mexico,” American Economic Review.

Jack, W, and T Suri (2014), “Risk Sharing and Transactions Costs: Evidence from Kenya’s Mobile Money Revolution,” American Economic Review, 104(1): 183-223.

Parker, S, and T Vogl (2018), “The Long-Term Effects of Cash Transfers: Mexico’s Progresa,” VoxDev. https://voxdev.org/topic/social-protection/long-term-effects-cash-transfers-mexicos-progresa.

Katz, M, and C Shapiro (1986), “Technology Adoption in the Presence of Network Externalities,” Journal of Political Economy, 94: 822-841.

Suri, T, J Aker, C Batista, M Callen, T Ghani, W Jack, L Klapper, E Riley, S Schaner, and S Sukhtankar (2023), “Mobile Money,” VoxDevLit 2(2). https://voxdev.org/sites/default/files/2023-09/Mobile_Money_2.pdf.