The aggregate annual loss to US consumers from higher import prices as a result of the trade war with China could be as much as $68.8 billion

The US has pushed for lower global trade barriers around the world for decades. These efforts reversed in 2018 when it implemented tariffs on 12.7% of its imports, raising tariffs on targeted imports from an average of 2.6% to 16.6%. Trade partners retaliated by targeting 8.2% of US exports, raising tariffs from an average of 7.3% to 20.4%. This episode is the largest return to protectionism by the US since the 1930 Smoot-Hawley Act and the 1971 ‘Nixon shock’ (Irwin 1998, Irwin 2013).

In a recent paper (Fajgelbaum et al. 2019), we estimate the impact of the trade war on the US economy. Our main findings are:

- large and immediate impacts of tariffs on trade flows;

- complete pass-through of US tariffs to variety-level import prices;

- a $51 billion annual loss to US consumers and firms from higher import prices;

- a $7.2 billion annual aggregate loss when producer gains and tariff revenue are factored in;

- US tariffs protected politically competitive counties, whereas retaliations targeted heavily republican counties; and

- on net, Republican counties are most negatively impacted by the trade war.

Import and export volumes and pass-through

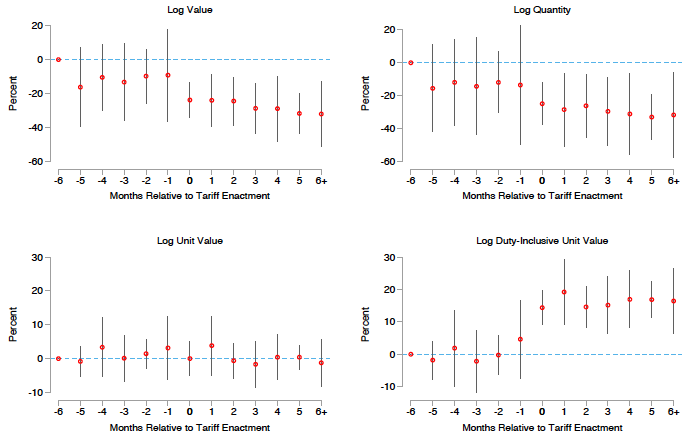

We use an event-study design on monthly US import data to document differential impacts on targeted imported and exported varieties relative to non-targeted varieties (varieties are defined as 10-digit product-country pairs). Documenting the absence of pre-trends is crucial for using the tariffs from the trade war as a source of identifying variation. Additionally, the event study analysis tests for anticipatory effects.

The event study in Figure 1 reveals four messages. First, prior to the trade war, targeted varieties were not on different trends. Second, anticipatory effects are quantitatively very small, implying that importers did not shift purchases forward.1 Third, we detect large and immediate impacts of tariffs: import volumes fall by 31.7%. Finally, we see complete pass-through of tariffs to duty-inclusive prices (i.e. before-duty prices do not fall), implying that the costs of US tariffs are paid by US importers. Amiti et al. (2019) and Cavallo et al. (2019) also find complete tariff pass-through to border prices in this trade war.

Figure 1 Import event study

We implement an analogous event study for US exports that examines the impacts of the retaliatory tariffs (Figure 2). The figure reveals that targeted US export varieties were not on differential trends, and no evidence of anticipatory behaviour. Upon implementation of the retaliatory tariffs, US exports fall sharply. We do not observe US exporters lowering before-duty unit values to retaliating countries relative to other countries.

Figure 2 Export event study

Aggregate impacts

The aggregate and distributional consequences of the trade war depend on the incidence of the tariffs. While the reduced-form evidence provides guidance, assessing these impacts requires structural elasticities. If changes in tariffs are uncorrelated with contemporaneous demand and supply shocks – a crucial assumption validated by the event studies and pre-trends checks – a single tariff can be used to simultaneously instrument both the imports demand and foreign export supply curves (Romalis 2007, Zoutman et al. 2018). Using this approach, we obtain variety-level import demand and export supply elasticities. We also obtain demand elasticities between imported products, and between imports and domestic goods. According to our estimates, we cannot reject a perfectly horizontal foreign supply curve.

The findings imply complete pass-through of tariffs to duty-inclusive import prices, a finding that is systematic across products with heterogeneous characteristics. The resulting real income loss to US consumers and firms who buy imports can be computed as the product of the import share of value added (15%), the fraction of US imports targeted by tariff increases (13%), and the average increase in tariffs among targeted varieties (14%). This decline is $51 billion, or 0.27% of GDP.

The previous results have two important caveats. First, our analysis considers short-run effects, but relative prices could change over longer horizons. Second, our estimation controls for country-time and product-time effects, and therefore is unable to capture import price declines due to relative wage changes across countries or sectors. In other words, the results do not imply that the US is a small open economy unable to affect world prices, as terms-of-trade effects could have occurred through wage adjustments at the country-sector level.2

We combine the previously estimated parameters with a supply side model of the US economy to gauge some of these effects. The model imposes upward sloping industry supply curves in the US and predicts changes in sector-level prices in the US due to demand reallocation induced by tariffs. We impose perfect competition, flexible prices, and flexible adjustment of intermediate inputs. To assess regional effects, we assume immobile labour and calibrate the model to match specialisation patterns across US counties. In the model, US tariffs reallocate domestic demand into US goods, raising total demand and therefore US export prices, while retaliatory tariffs have the opposite effect. These price changes are qualitatively consistent with suggestive evidence that US tariffs led to increases in the PPI and that sector-level export prices fell with retaliatory tariffs.

The results of our counterfactuals are summarised below (Table 1). We estimate producer gains of $9.5 billion, or 0.05% of GDP. Adding up these gains, tariffs revenue, and the losses from higher import costs yields a short-run loss of the 2018 tariffs on aggregate real income of $7.2 billion, or 0.04% of GDP. Hence, we find substantial redistribution from buyers of foreign goods to US producers and the government, but a small net loss for the US economy as a whole (which is not statistically significant at conventional levels after accounting for the parameters’ standard errors). While we cannot reject the null hypothesis that the aggregate losses are zero, the results strongly indicate large consumer losses from the trade war. If trade partners had not retaliated, the economy would have experienced a modest (and also not statistically significant) aggregate loss.

Table 1 Aggregate impacts of the trade war on the US

Regional consequences, structure of protection and electoral incentives

The small aggregate effects mask heterogeneous impacts across regions.

Figure 3 shows that import tariffs provided the most protection to sectors that tend to be geographically concentrated in Rust Belt states like Michigan, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. By contrast, foreign countries targeted their retaliations on agriculture sectors primarily located in Midwestern and mountain states such as Iowa, Kansas, Idaho, and North and South Dakota (Figure 4).

Figure 3 Import tariff exposure in US counties

Figure 4 Export tariff exposure in US counties

If workers are regionally immobile, this regional heterogeneity generates distributional impacts. Using the model, we compute a standard deviation of real wages in the tradeable sectors across counties of 0.5%, relative to an average real wage decrease of 1%.

Why did the US target some sectors for import protection but not others? We probe the hypothesis that the structure of protection was motivated by electoral incentives. Figure 5 plots changes in import tariff exposure against the 2016 GOP presidential vote share at the county level. The figure provides suggestive evidence that the US tariffs may have aimed to protect electorally competitive counties with a 40-60% GOP vote share. Foreign countries, on the other hand, targeted rural, agriculture counties that voted strongly in favour of the GOP in 2016.

Figure 5 Tariff exposure versus GOP vote share

As a result of these retaliations, we compute that very Republican counties are hit hardest by the trade war. As shown in Figure 6, relative to a heavily Democratic county (with a 5-15% GOP vote share), the welfare losses in a heavily Republican county (with an 85-95% GOP vote share) are 32% larger.

Figure 6 Real tradable wage loss versus GOP vote share

Conclusion

Our research has aimed to help scholars and policymakers understand the short-run effects of the trade war on the US economy. Our analysis does not consider the impacts of the trade war on economic uncertainty, productivity and innovation, or long-run economic outcomes. Future research in these areas would provide a valuable complement to this study and to ongoing debates about optimal trade policy.

Editors' note: This column first appeared on VoxEU.

References

Amiti, M, S Redding, and D Weinstein (2019), “The Impact of the 2018 Trade War on U.S. Prices and Welfare,” CEPR Discussion Paper 13564.

Bagwell, K and R W Staiger (1999), “An Economic Theory of GATT,” American Economic Review 89: 215–248

Caliendo, L, F Parro, E Rossi-Hansberg, and P-D Sarte (2017), “The Impact of Regional and Sectoral Productivity Changes on the US Economy,” The Review of Economic Studies 85: 2042–2096.

Fajgelbaum, P, P Goldberg, P Kennedy, and A Khandelwal (2019), “The Return to Protectionism,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, forthcoming.

Irwin, D A (1998), “The Smoot-Hawley Tari: A Quantitative Assessment,” The Review of Economics and Statistics 80: 326–334.

Irwin, D A (2013), “The Nixon Shock After Forty Years: the Import Surcharge Revisited,” World Trade Review 12: 29–56

Zoutman, F T, E Gavrilova, and A O Hopland (2018), “Estimating Both Supply and Demand Elasticities Using Variation in a Single Tax Rate,” Econometrica 86: 763–771.

Endnotes

[1] We also confirm the lack of pre-trends and anticipatory effects by looking at correlations between changes in outcomes during the trade war and previous changes in tariffs and at dynamic specifications with leads and lags.

[2] Bagwell and Staiger (1999) demonstrate that trade agreements serve to deal with terms-of-trade externalities.