New evidence on malnutrition risks among 1.27 million children from 44 low- and middle-income countries quantifies the significant negative health effects caused by rising food prices

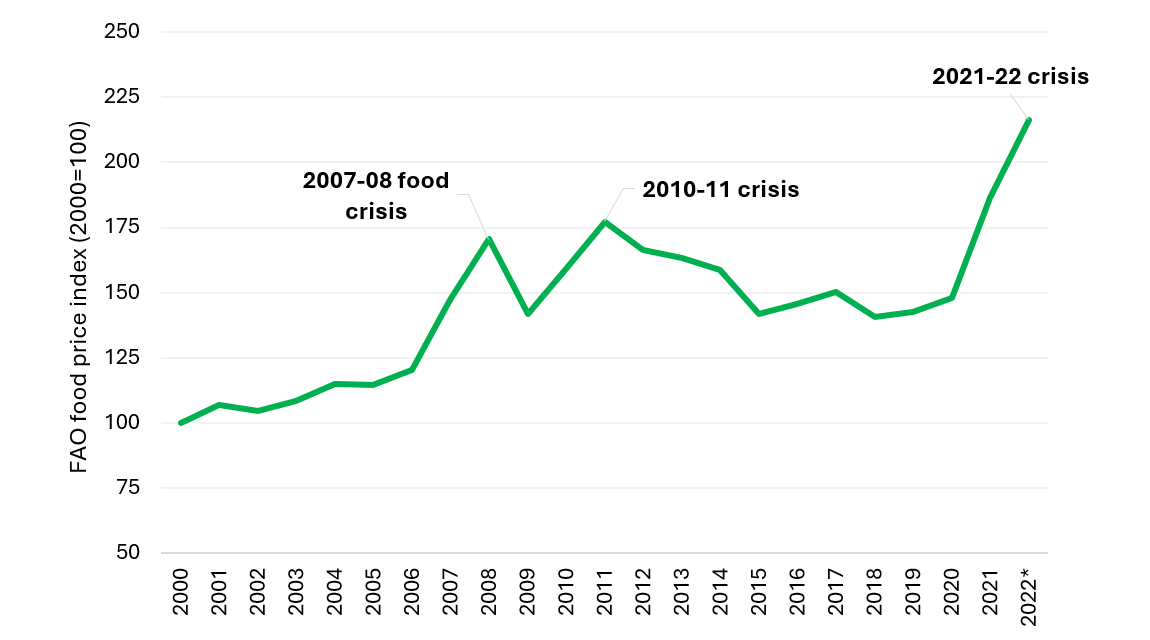

The real price of food has risen dramatically in 21st century, with the FAO food price index peaking at an all-time high in March 2022 at 116% above its 2000 value (Figure 1). While food inflation has long been a cause of concern for nutrition agencies in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), new evidence is shedding light on the potential impacts of rising food prices on child malnutrition in LMICs.

Figure 1: Rising real food prices and repeated crises in the 21st Century: Trends in the FAO real international cereal price index from 2000 to August 2022

Notes: Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Data are the author’s construction from the real FAO cereal price index.

Economists have long been interested in assessing whether rising food prices exacerbate or reduce poverty in LMICs. While higher food prices obviously hurt the urban poor, many of the world’s poor live in rural areas and earn incomes from farming and selling food. The Nobel prize-winning economist, Angus Deaton (1989), argued that the short run impact of higher food prices on a household’s income depends on whether it produces more food than it consumes. However, the economic evidence of food price increases and poverty is inconclusive, with simulation studies finding that poverty increases as food prices rise, and survey evidence finding the opposite, at least in rural areas (Headey and Hirvonen 2023).

If the poverty evidence is inconclusive, the evidence on the impacts of rising food prices on malnutrition is virtually non-existent, bar a single innovative study from Mozambique (Arndt et al. 2016). This evidence gap exists despite the fact that acutely malnourished children are 13 times more likely to die before their 5th birthday, while chronically malnourished children too short for their age (stunted) who have suffered a lifelong history of poor nutrition are significantly more likely to have poor health, slowed cognitive development and schooling attainment, and lower wages in adulthood. To close this evidence gap, our new large-scale study examines associations between real food price changes and child wasting and stunting across 44 LMICs with Demographic Health Surveys (DHS) implemented over 2000-2021 (Headey and Ruel 2023).

Food price shocks and malnutrition among 1.27 million children

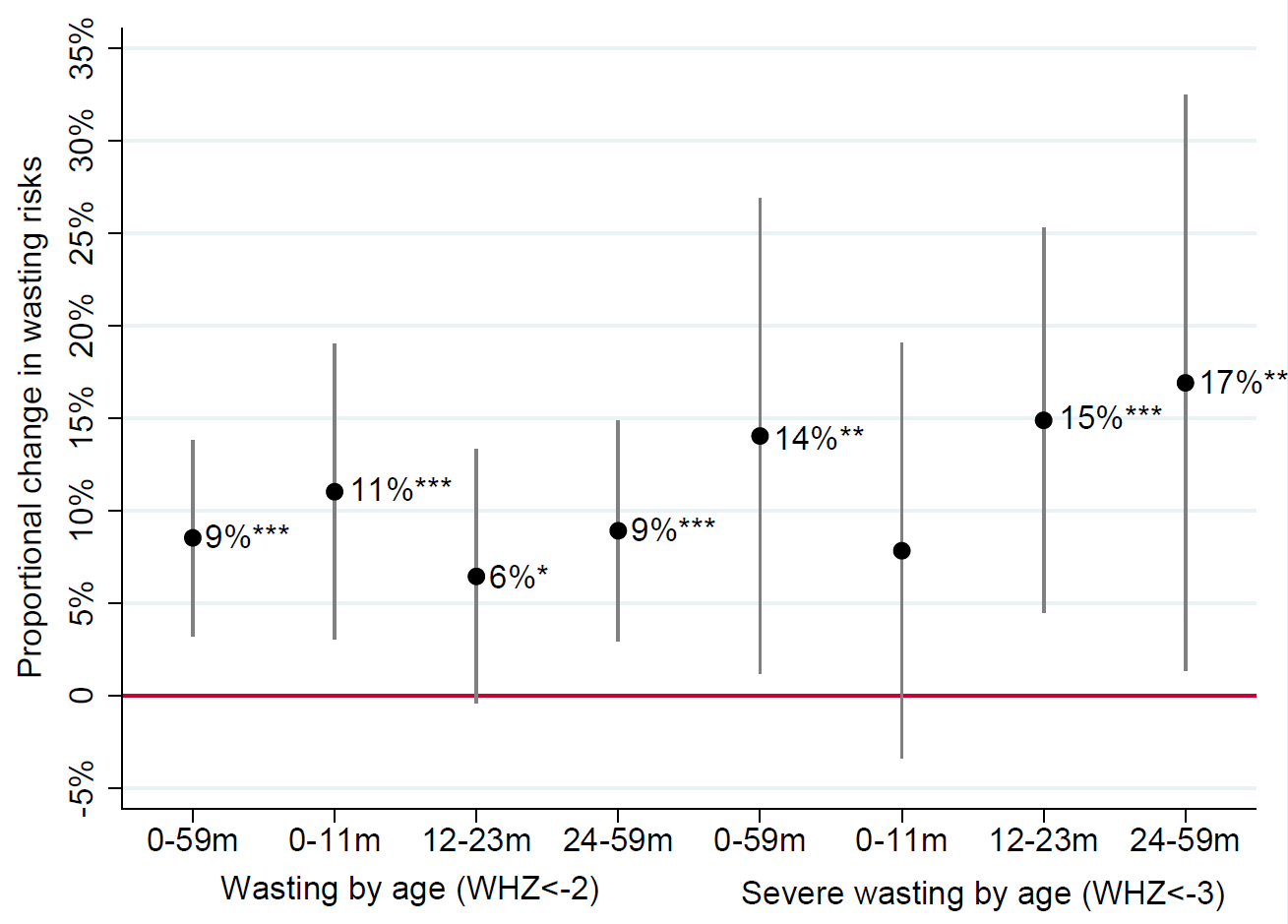

Figure 2 reports estimates of the predicted impacts of a 5% increase in the real price of food over a 3-month period on the subsequent risk of wasting/severe wasting over different early-life age ranges. A 5% real price rise predicts a 9% increase in wasting risks and a 14% increase in severe wasting risks. Effect sizes are larger among younger children, suggesting adverse impacts even in the womb due deterioration in maternal nutrition during inflationary episodes.

Figure 2: Coefficients representing the change in child wasting risks from a 5% increase in the real food price index over the 3 months prior to measurement, by child age

Notes: 95% confidence intervals based on standard errors clustered at the country level are reported in parentheses. *, ** and *** represent statistical significance at the 10%, 5% and 1% level respectively from a two-sided test. See Headey and Ruel (2023) for details. The full sample includes 1.271 children in 44 LMICs.

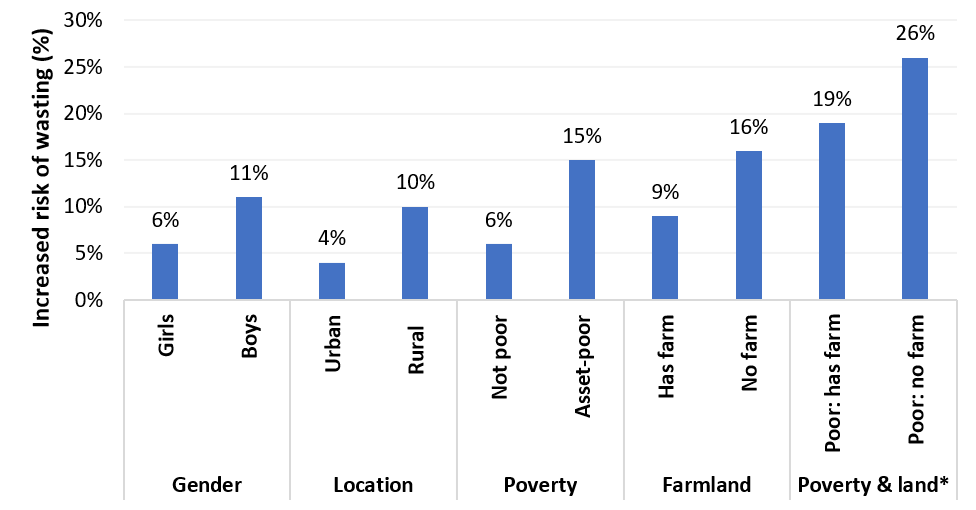

The effects of food price increases vary by other factors too (Figure 3). Young boys are more vulnerable than girls (indeed, even male fetuses generally tend to be more vulnerable to shocks), and children from rural and asset-poor households are also more vulnerable. However, in line with farming households being somewhat insulated from food price shocks, we found that children from households who owned farmland were less likely to become wasted than children from landless rural households. Moreover, all these effects are additive. The last two bars in Figure 3 show that a 5% rise in the real price of food predicts a 26% increase in the risk of wasting for children from households that are both asset-poor, compared to a 19% increased risk for children from asset-poor households that owned at least some farmland.

Figure 3: The heterogenous impacts of a 5% increase in real food prices on child wasting, by gender, location, poverty status and farmland ownership

Notes: Results are based on Table 1 in Headey and Ruel (2023), which uses interaction terms between food price shocks and the attributes described on the x axis. All coefficients are significant at the 5% level in two-sided tests. *Poverty and land results refer to effects for boys and girls combined based on additive effects of being poor and owning/not owning land.

Food inflation in the first 1000 days of life and subsequent stunting risks

Even brief nutritional insults in the first 1000 days of life – from conception to roughly two years of age – can affect a child’s growth for years into the future, and even determine adult stature. We therefore tested whether food inflation in the prenatal period or the first or second years after birth constitute longer-term risk factors for stunting in the post-1000 days 24-59 month age range. We found that a 5% increase in food prices in the prenatal period increases the risk of subsequent stunting by 1.6% and severe stunting by 2.4%, consistent with food price shocks raising the risk of wasting among newborns and infants. However, we also find significant effects of food price shocks in the first year after birth, consistent with the well-known nutritional vulnerability of infants.

Food inflation’s effect on the dietary quality of young children

Malnutrition stems from poor diets and disease, but food inflation likely works through dietary pathways. To test this, we tested whether food prices predict changes in achievement of adequate dietary diversity, defined as a child consuming at least four of seven healthy food groups in the past 24 hours. This simple indicator has been shown to predict the adequacy of children’s consumption of calories, vitamins and minerals, and in our study we show that dietary diversity is also predictive of reduced risks of wasting and stunting. However, our key finding is that a 5% real food price in the past 12 months predicts a 3% decrease in the probability that a child will have an adequately diverse diet.

This isn’t surprising from an economic perspective, because as food prices increase and disposable income declines, people switch to cheaper sources of calories; i.e. starchy staples. Unfortunately, nutritious foods like fruits, vegetables, and animal-sourced foods can be anywhere between 5 and 15 times more expensive than calories from starchy staples like rice, wheat, or corn in LMICs, making nutrient-rich foods economically even more unattractive to the poor during a crisis (Headey and Alderman 2019).

Protecting vulnerable children when food price volatility is the new normal

For the first time the scientific community has solid cross-country evidence that the nutritional status of young children is highly vulnerable to food price shocks, which seem increasingly frequent and severe in the 21st century. Since such shocks have harmful effects during pregnancy as well as in early childhood, maternal and child cash and/or nutritious foods transfers might be an effective means of preventing malnutrition and related mortality throughout the first 1000 days (and potentially beyond), especially if they are combined with effective diet and nutrition-focused social behaviour change communication (Maffioli et al. 2023) and if cash transfers are adjusted for inflation. In an era of heightened food price volatility and more frequent extreme weather events there is an urgent need for greater investment in monitoring nutrition, food security and economic welfare at high frequency and real time (Headey and Barrett 2015). Programmes to prevent and treat severe malnutrition also need to be strengthened and equipped to maintain full operation during times of crises.

Finally, food systems at the local, national, regional and global level require actions to make these systems more productive and sustainable, more equitable and inclusive, and more resilient to the complex economic, political and environmental shocks that are hitting food systems with increasing regularity and severity.

References

Arndt, C, M A Hussain, V Salvucci and L P Østerdal (2016), “Effects of food price shocks on child malnutrition: The Mozambican experience 2008/2009.” Economics & Human Biology 22: 1-13. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1570677X16300119

Deaton, A (1989), “Rice prices and income distribution in Thailand: a non-parametric analysis.” Economic Journal 99: 1-37. https://academic.oup.com/ej/article-abstract/99/395/1/5190210

Headey, D and K Hirvonen (2023), “Higher food prices can reduce poverty and stimulate growth in food production.” Nature Food 4: 699-706. https://www.nature.com/articles/s43016-023-00816-8

Headey, D and M Ruel (2023), “Food inflation and child undernutrition in low and middle income countries.” Nature Communications 14: 5761. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-023-41543-9

Headey, D and C B Barrett (2015), “Opinion: Measuring development resilience in the world’s poorest countries.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112: 11423-11425. https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1512215112

Headey, D D and H H Alderman (2019), “The Relative Caloric Prices of Healthy and Unhealthy Foods Differ Systematically across Income Levels and Continents.” The Journal of Nutrition 149: 2020-2033. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/nxz158

Maffioli, E M, D Headey, I Lambrecht, T Z Oo and N T Zaw (2023), “A Prepandemic Nutrition-Sensitive Social Protection Program Has Sustained Benefits for Food Security and Diet Diversity in Myanmar during a Severe Economic Crisis.” The Journal of Nutrition 153: 1052-1062. https://10.1016/j.tjnut.2023.02.009