Evidence on schooling decisions in Mexico City reveals what the impact of performance feedback in education would be if implemented at a large scale.

In recent years, economics and other social sciences have increasingly relied on randomised evaluations to directly inform policy making. The compelling evidence provided by field experiments has contributed to the implementation of effective programmes and/or policies in various countries (Duflo 2020). However, such a laudable goal has been undermined by a “scale-up problem”. This is the tendency for the size effect of an intervention to diminish, if not vanish, when they are scaled up to reach a larger and more diverse population (List 2022).

A few studies have focused on the implementation challenges associated with scaling up (see, e.g. Banerjee et al. 2017, Agostinelli et al. 2024, and the accompanying VoxDev article). Another key issue is that spillover and equilibrium effects may fundamentally alter the inference drawn from small-scale pilot studies (Heckman et al. 1998). In recent research (Bobba et al. 2024), we assess the generalisability of the results from a randomised evaluation of an information intervention that provides students with individualised feedback about their academic skills.

School choice in Mexico City

The setting of our analysis is the secondary education market of the metropolitan area of Mexico City, in which a centralised clearinghouse coordinates admission to public high schools in the region. Close to 300,000 students apply every year to the system by submitting rank-ordered lists of high school programmes by early March. At the end of June all applicants take a unique standardised admission test that determines priority in the assignment system and assesses curricular knowledge as well as verbal and analytical aptitude. The Mexican case is not unique; several school and college assignment mechanisms around the world are similar. As a result, high stake decisions regarding schooling and occupational trajectories may not incorporate relevant information about an applicant’s academic skills (e.g. Ghana, Kenya, Barbados, Trinidad and Tobago, among others). In our sample, over 80% of the students overestimate their performance in the test by the time they apply to the system.

How does providing information to socio-economically disadvantaged students affect school choice

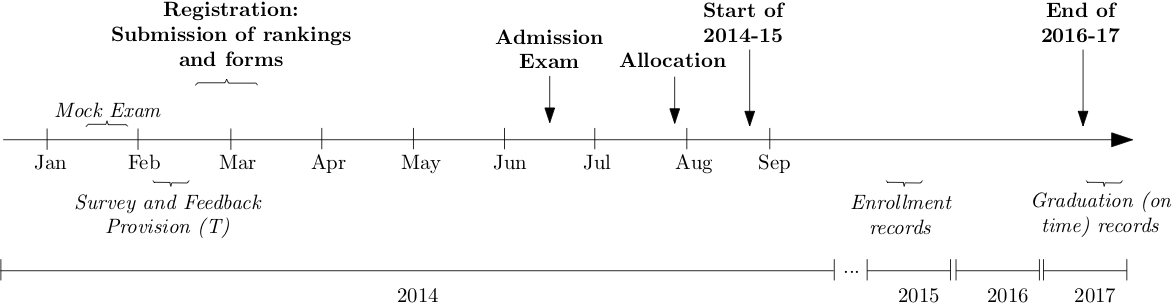

We administer a mock version of the admission test among a socio-economically disadvantaged sample of approximately 1% of the applicants (N=2,493) across 90 middle schools and communicate individual score results to a randomly chosen sub-sample before the school rankings are submitted (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Timeline of events and the information intervention

Providing individual feedback on exam scores substantially shifts students’ belief distributions regarding own academic performance. We document relatively larger updates among lower performing students, who display wider gaps between the expected score and their actual performance in the mock exam. For an in-depth analysis of the process of belief updating spurred by the performance feedback, see our companion paper (Bobba and Frisancho 2022).

On average, the information intervention does not systematically alter school choices. However, the treatment has differential effects depending on students’ academic skills: better performing (lower performing) students who received performance feedback increase (decrease) the share of academic vis-a-vis non-academic options in their school rankings when compared to those who do not receive any feedback. The improved alignment between skills and school programmes translates into differential placement outcomes, which, in turn, alter educational attainment. Three years after school assignment, the probability of graduating from high school on time is, on average, 13% higher for students who received the feedback when compared to the sample average of those who did not.

Does scaling up the programme change its impact?

The score in the mock exam provides students with an informative signal about their academic skills that is easy to replicate for the broader population of the applicants. We thus study the effect of scaling up the information provision intervention by simulating the impact of mandating the universal implementation of a mock exam or, equivalently, disclosing the actual admission exam scores to the applicants before the submission of the rank-ordered lists.

Using the experimental variation and data for all applicants we estimate a model of school choice to predict the sorting pattern of students i.e. which schooling alternative students will choose under the status quo and the counterfactual regime of information provision.

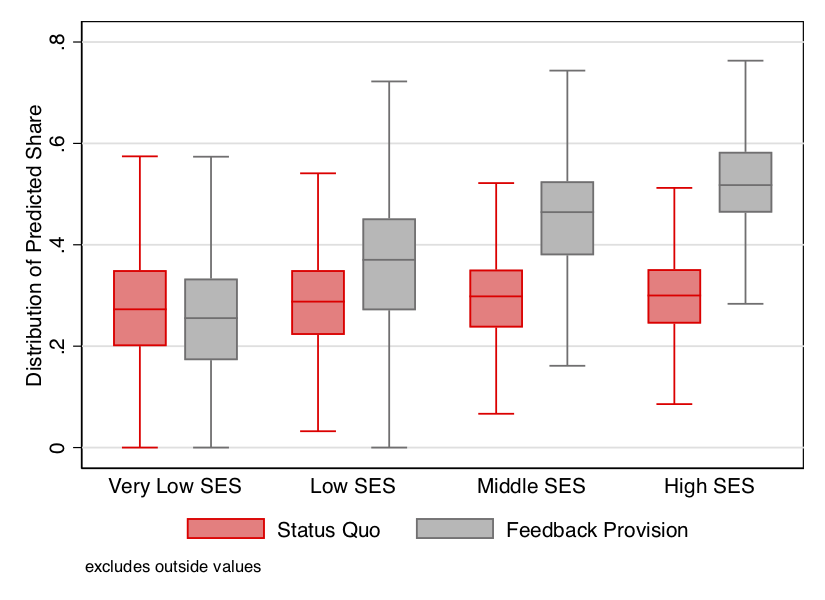

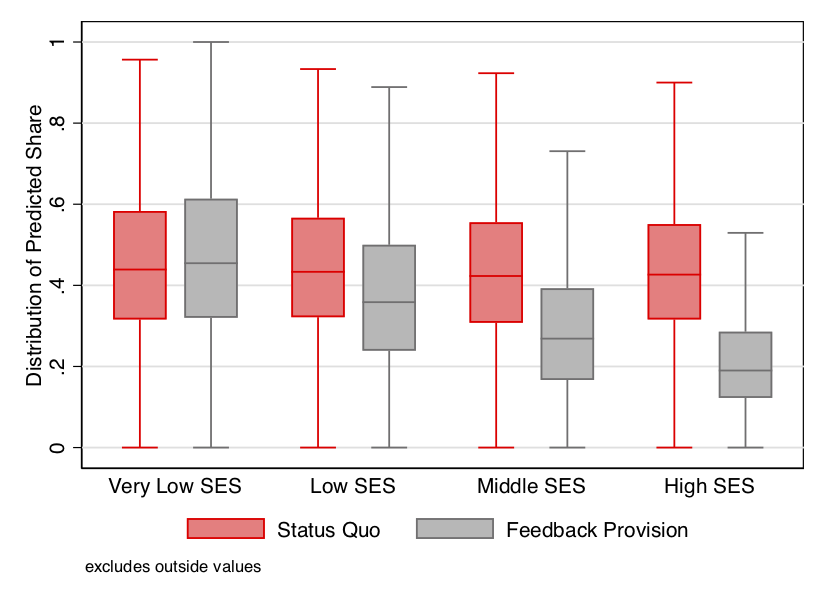

We observe that the majority of the change in school choice between the status quo and the counterfactual occurs among applicants who are socio-economically better off (high-SES). These students increase their demand for academic schools and symmetrically decrease the demand for selective and prestigious (elite) schools as a result of performance feedback. Low-SES students are, on average, unresponsive to the information intervention (see figure 2), which is consistent with the small and insignificant average effect documented in our experimental sample of socio-economically disadvantaged students.

Figure 2: The effect of providing performance feedback on track choices

Panel A: Share of Academic Schools by SES Panel B: Share of Elite Schools by SES

Note: This figure displays box- and-whisker plots for the shares of academic schools and elite schools as implied by the model estimates for the control group (red bars) and for the treatment group (grey bars). The central lines within each box denote the sample medians, whereas the upper and lower level contours of the boxes denote the 75th and 25th percentiles, respectively. The whiskers outside of the boxes denote the upper and lower adjacent values, which are values in the data that are furthest away from the median on either side of the box but are still within a distance of 1.5 times the interquartile range from the nearest end of the box (i.e., the nearer quartile).

Overall, the provision of performance feedback improves matching outcomes. Moving from the status quo to a scenario with performance feedback, the share of students assigned to their most preferred option increases by nine percentage points, from 16% to 25%. The lower demand-side pressure on selective and prestigious programmes crowds in high achieving and low-SES applicants through congestion externalities, which increase their representation at elite schools by more than 20 percentage points. We do not observe changes at the extensive margin: there are no effects in the decision to participate in the school admission process.

How does performance feedback affect educational attainment?

Our school choice model gave us predictions on the schooling alternatives students would choose under performance feedback and the status quo. We integrate these results into a school value added framework to try and understand how these choices affect educational attainment.

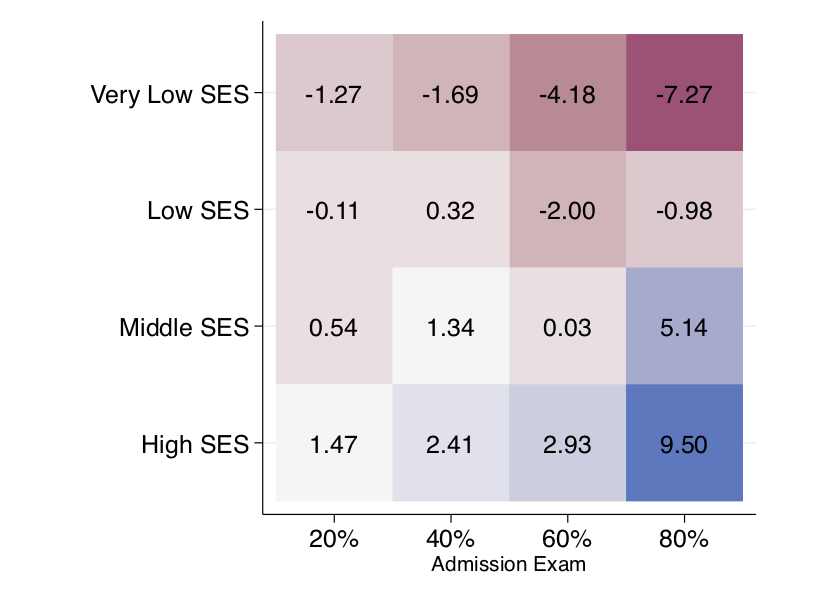

The model estimates imply that attending an elite school has a large and negative effect on the probability of obtaining a secondary education degree. By opting out from elite schools towards other academic schools, high-SES applicants would increase school completion rates by 2 to 9 percentage points depending on their admission score (see figure 3). Conversely, because more low SES applicants are attending elite schools under performance feedback, they are now performing worse in terms of high-school graduation. This is particularly the case for those with a relatively high admission score, who would be 4-7 percentage points less likely to complete upper secondary education on time.

Figure 3: The effect of providing performance feedback on high-school graduation

Note: This figure shows the percentage changes, by discrete categories of socio-economic status (y-axis) and the score in the admission exam (x-axis), between the Information Policy and the Status Quo scenarios in the shares of applicants who complete the high-school programme of their assignment in the centralised system.

Implications for scaling up information interventions in education

The discrepancy between the results we obtain from the model-based evidence at scale and the small-scale experimental evaluation can be explained by an equilibrium effect across high-school tracks. The lower demand-side pressure from high-SES students leaves some open seats at elite high-school programmes for disadvantaged students with high admission scores, which ultimately hampers inequality in education outcomes. In this sense, successfully scaling up the intervention may require providing additional signals that are targeted at disadvantaged students and are informative about the individual probability of graduation, conditional on attending different high-school programmes.

Our findings offer a novel perspective of the impact of information provision in centralised education markets. Access to more accurate information about skills is shown to enhance the ex-ante efficiency of the allocation of students across schools. However, the distributional consequences are far more nuanced; in our study, they depend on the extent of the congestion externalities across schools. Large-scale policy changes therefore must account for such equilibrium effects.

References

Agostinelli, F, C Avitabile, and M Bobba (2024), “Enhancing human capital in children: A case study on scaling,” Journal of Political Economy, forthcoming.

Banerjee, A V, R Banerji, J Berry, E Duflo, H Kannan, S Mukerji, M Shotland, and M Walton (2017), “From proof of concept to scalable policies: Challenges and solutions, with an application,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(4): 73–102.

Bobba, M, and V Frisancho (2022), “Self-perceptions about academic achievement: Evidence from Mexico City,” Journal of Econometrics, 231(1): 58–73.

Bobba, M, V Frisancho, and M Pariguana (2024), “Perceived ability and school choices: Experimental evidence and scale-up effects,” Discussion Paper DP19238, Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR).

Duflo, E (2020), “Field experiments and the practice of policy,” American Economic Review, 110(7): 1952–73.

Heckman, J J, L Lochner, and C Taber (1998), “General-equilibrium treatment effects: A study of tuition policy,” American Economic Review, 88(2): 381–386.

List, J A (2022), “The voltage effect: How to make good ideas great and great ideas scale,” Penguin Books.