Access to 3G broadband internet in Indonesia reduced COVID-19 cases by approximately 45%, a relatively large impact compared to the effectiveness of other non-pharmaceutical interventions. Areas with higher literacy rates and a greater ability to telework experienced even more pronounced benefits.

Editor's note: This article originally appeared on VoxEU.

The potential for digital access to significantly improve productivity in healthcare services has been widely recognised (e.g. Miller and Tucker 2011, Agha 2014). This potential is particularly relevant in lower-income countries, where physical healthcare infrastructure is often inadequate, resulting in persistent issues and disparities in healthcare access and outcomes across different regions and communities (Barber et al. 2007, Van de Poel et al. 2007). However, the question of whether digital access can effectively substitute physical healthcare resources remains unresolved (Kahn et al. 2010, Malamud et al. 2019, Valletti et al. 2020, Kickbusch et al. 2021, Giaccherini et al. 2024). This issue becomes even more crucial during health crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic (Arman et al. 2022, Picard et al. 2022). While physical infrastructure is essential, it can sometimes facilitate the spread of diseases through increased physical contact. Digital infrastructure, conversely, offers a more flexible and potentially cost-effective alternative by enabling telemedicine and supporting remote work.

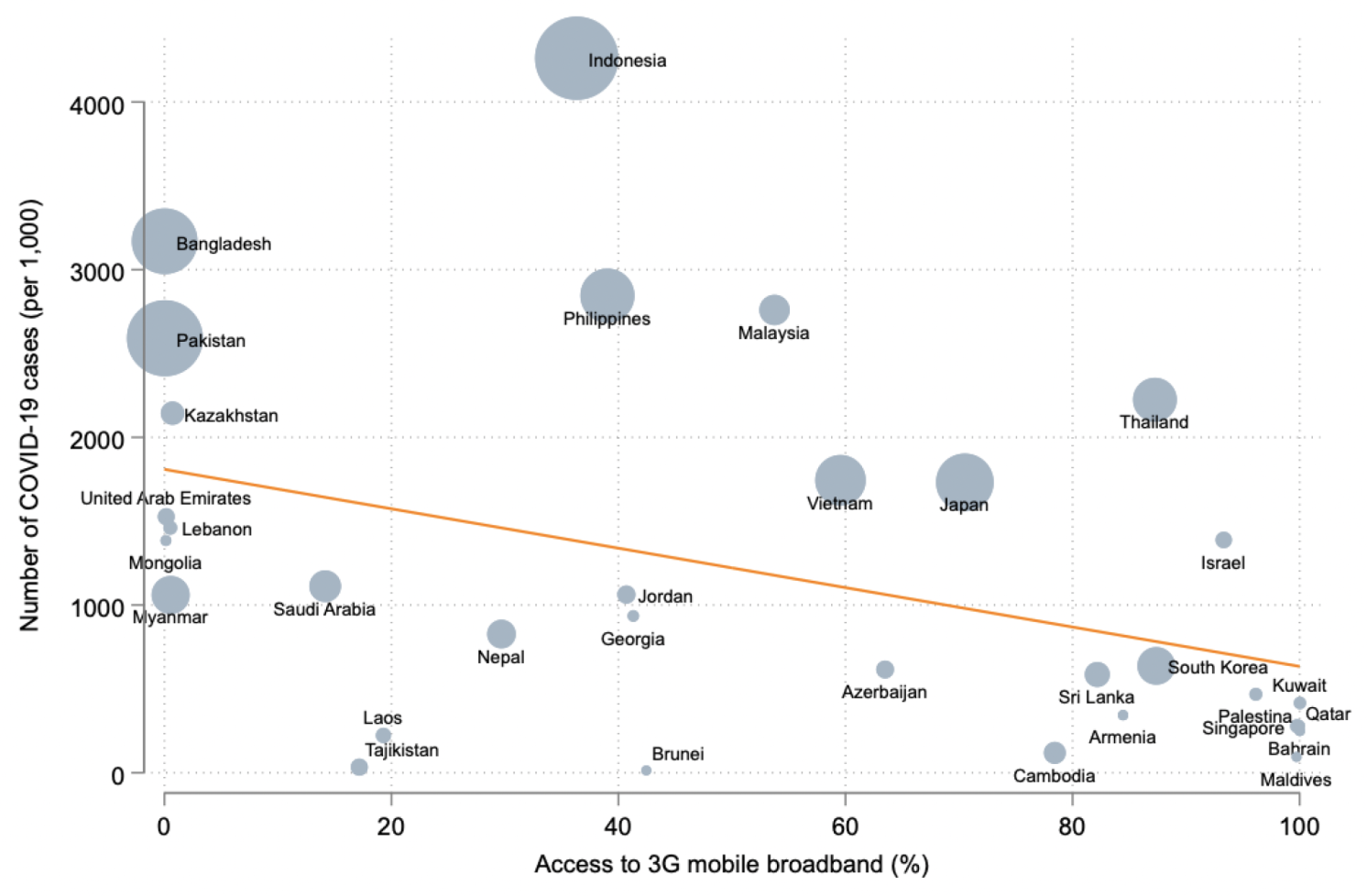

In a recent paper (Kunz et al. 2024), we explore the impact of internet access on health outcomes by examining the effect of digital connectivity on the spread of COVID-19 in Indonesia, a developing country with considerable variations in mobile internet access and COVID-19 cases across different regions. At the beginning of 2023, Indonesia emerged as a major epicenter of the Southeast Asian pandemic, with a notably high number of confirmed cases compared to its regional peers. As shown in Figure 1 (top panel), the relationship between COVID-19 cases and internet access is clearly visible, with Indonesia standing out among Asian nations, having a high number of cases but relatively low mobile internet access. The bottom panel shows a strong and significant negative association of cases and internet coverage across regencies (provinces) within Indonesia.

Figure 1: Mobile broadband access and COVID-19 cases: Asia region and within Indonesia

Source: Kunz et al. (2024).

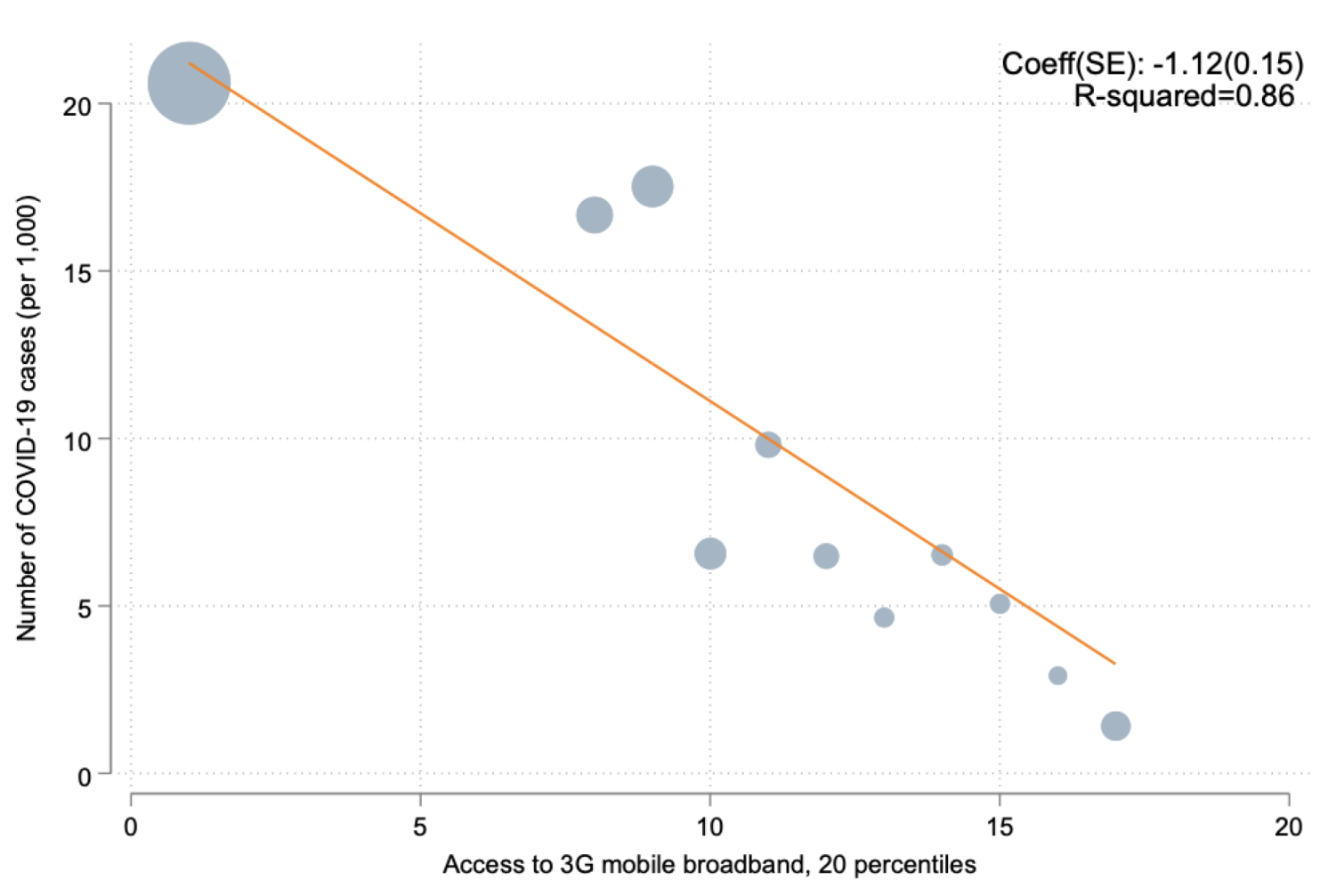

In our paper we exploit the large variation within Indonesia in the availability of digital infrastructure (specifically cellular towers) at the regional level. We address the fact that the expansion of mobile network coverage, like other types of infrastructure, is often influenced by endogenous factors. For instance, network service providers typically prioritise areas with high economic activity and potential demand, which can be correlated with other factors that affect the spread of the pandemic. Consequently, the straightforward conditional relationship between mobile internet penetration and COVID-19 spread may not accurately reflect the causal impact. To address this issue, we use an instrumental variable (IV) strategy using lightning strikes (following, inter alia, Guriev et al. 2021). The rationale behind this approach is that lightning strikes can cause significant damage to digital infrastructure, resulting in localised blackouts and thus lack of access. This IV is particularly suitable for countries near the equator, including Indonesia, with a high frequency of lightning strikes (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Global lightning strike distribution

Source: Kunz et al. (2024).

Key findings

We find that internet access significantly impacted the spread of COVID-19 in Indonesia. There is a strong unconditional relationship between internet access and a lower number of cases. However, this may simply reflect the fact that areas which have fewer cases are those in which individuals who are richer live and in which more towers are erected. Utilising lightning strikes as an instrumental variable to address potential sources of endogeneity and controlling for a wide range of demographic, social, and labour market characteristics, we find a significant positive relationship between lightning strikes and COVID-19 cases. The magnitude is large: a one standard deviation increase in internet exposure is estimated to have reduced the number of cases by about 45%.

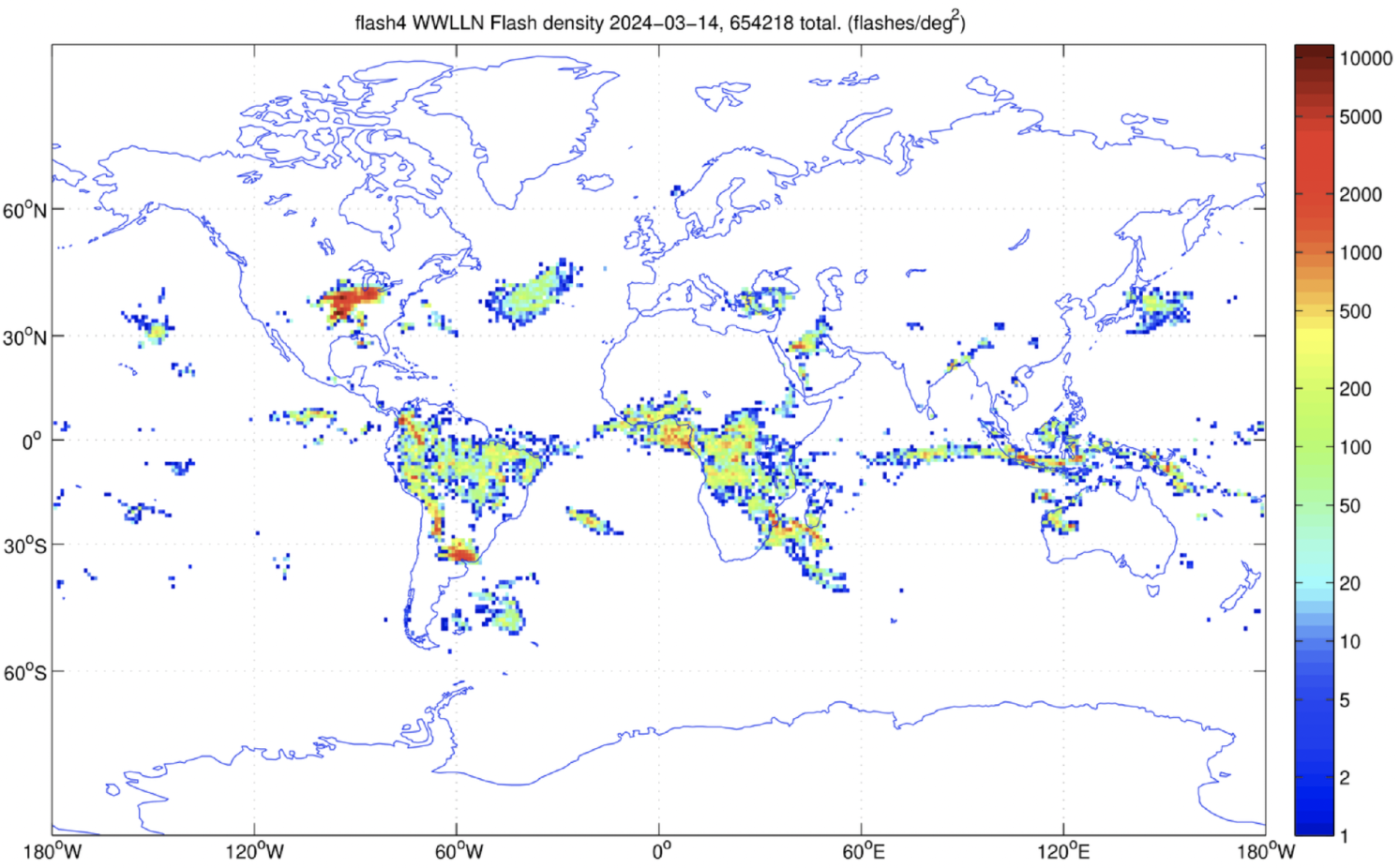

The temporal analysis in Figure 3 demonstrates that regions with internet access experienced a stable divergence in case numbers early in the pandemic, persisting despite the emergence of new variants and vaccine rollouts, highlighting the crucial role of digital connectivity in mitigating the spread of COVID-19.

Figure 3: Effects throughout the pandemic

Source: Kunz et al. (2024).

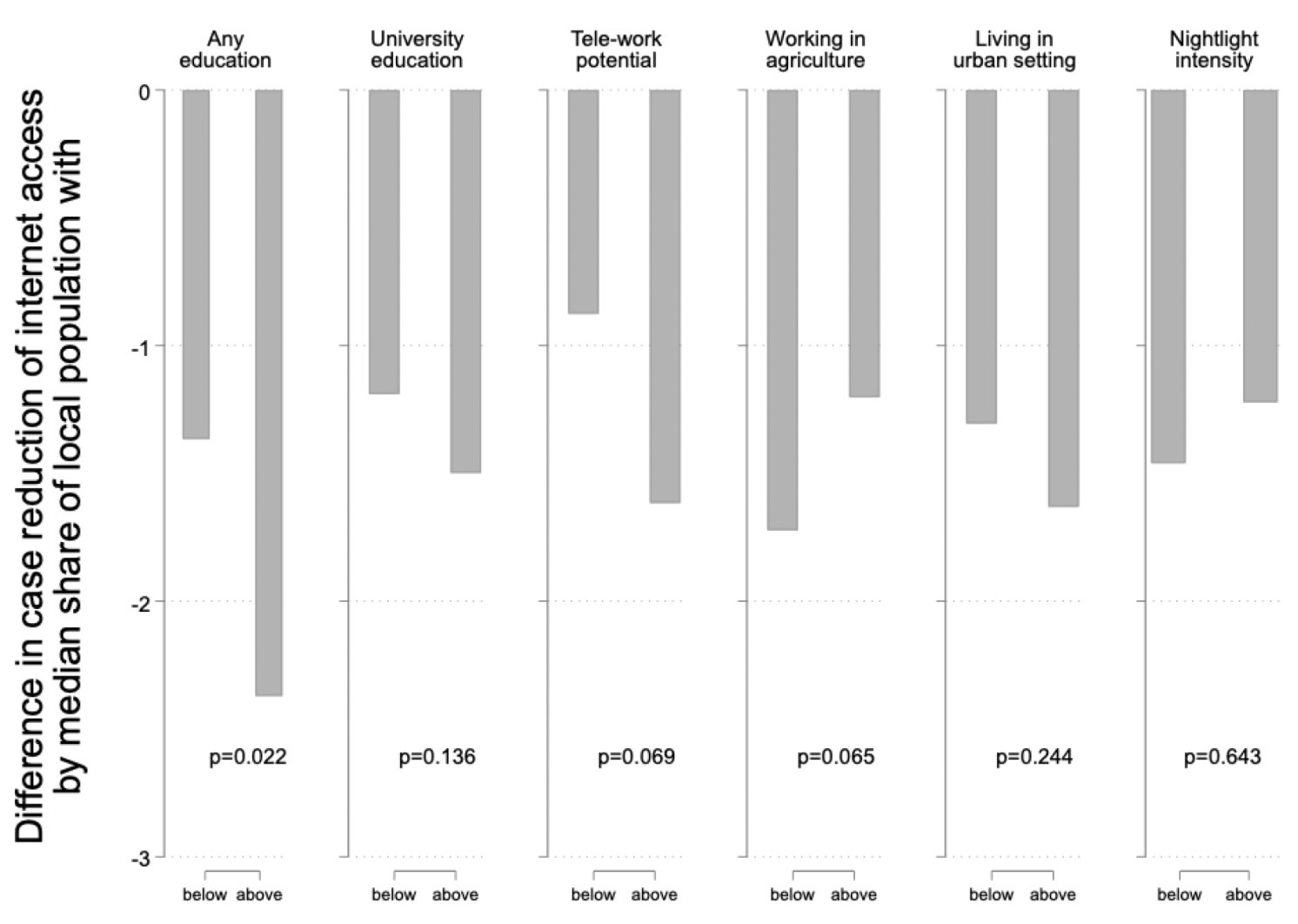

To understand whether certain areas benefited more from internet exposure, we examine the differential effects across various factors such as educational levels, labour force characteristics, urbanicity, and economic activity. Figure 4 highlights two key findings. First, the benefits of internet access in reducing COVID-19 transmission are significantly more pronounced in populations with higher educational levels. Specifically, the data indicate that basic literacy is essential for leveraging the benefits of internet access, as the difference in transmission rates between those with no or only primary education and those with secondary or more education is both statistically significant and substantial.

Second, we explore the variations in industry structure and find that regions with a higher potential for remote employment (telework) exhibited greater benefits from internet access. This is because teleworking reduces the need for commuting and face-to-face interactions, thereby decreasing transmission risks. Conversely, areas with a large agricultural sector, where remote work is less feasible, showed diminished benefits from internet access. Further analysis reveals that these differences are not simply reflections of underlying economic development or population density. Regions with higher urbanicity derived more benefits, despite potentially higher population densities, while areas with greater economic development, indicated by nightlight intensity, experienced marginally fewer benefits. These findings underscore the importance of digital literacy and the ability to adapt to remote work in maximising the public health benefits of internet access during a pandemic.

Figure 4: Heterogeneity analysis

Source: Kunz et al. (2024).

Implications of our findings

Our study examines the relationship between internet coverage and health outcomes, using the COVID-19 pandemic as an unexpected health shock to explore the role of digital connectivity in mitigating virus spread. Focusing on Indonesia, we utilise an IV framework to isolate the effect of internet access on public health. Our results show that 3G broadband access reduced COVID-19 cases by approximately 45%, suggesting that improving connectivity by 30% could have prevented 1.8 million cases over three years, bringing Indonesia closer to its peers (i.e. Philippines or Vietnam, see Figure 1, top panel). This impact is comparable to or even greater than other non-pharmaceutical interventions like social distancing and mask-wearing, making it a critical component of broader health emergency preparedness strategies (Asian Development Bank 2024). Regions with higher literacy levels and greater capacity for telework benefited more, highlighting the importance of educational and infrastructural readiness. Additionally, the sustained divergence in COVID-19 growth rates between areas with and without early internet access underscores the ongoing importance of digital connectivity in curbing virus spread. These findings reaffirm the critical role of digital infrastructure in supporting public health interventions amidst evolving challenges.

References

Agha, L (2014), “The effects of health information technology on the costs and quality of medical care”, Journal of Health Economics 34: 19-30.

Armand, A, B Augsburg, A Bancalari and K K Kameshwara (2022), “Social Proximity and Misinformation: Experimental Evidence from a Mobile Phone-Based Campaign in India”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 16492.

Asian Development Bank (2024), “What Has COVID-19 Taught Us About Asia’s Health Emergency Preparedness and Response?”, Manila, Phillippines.

Barber, S L, P J Gertler and P Harimurti (2007), “Differences In Access To High-Quality Outpatient Care In Indonesia: Lower quality in remote regions and among private nurses is a manifestation of the educational, policy, and regulatory frameworks upon which the Indonesian health system is based”, Health Affairs 26(Suppl2): w352-w366.

Giaccherini, M, J Kopinska and G Rovigatti (2024), “The effects of vaccine scepticism on public health and the amplifying role of social media: Insights from Italy”, VoxEU.org, 4 April.

Guriev, S, N Melnikov and E Zhuravskaya (2021), “3G internet and confidence in government”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 136(4): 2533-2613.

Kahn, J G, J S Yang and J S Kahn (2010), “‘Mobile’ health needs and opportunities in developing countries”, Health Affairs 29(2): 252-258.

Kickbusch, I, D Piselli, A Agrawal et al. (2021), “The Lancet and Financial Times Commission on governing health futures 2030: growing up in a digital world”, The Lancet 398(10312): 1727-1776.

Kunz, J, C Propper and T A Trinh (2024), “Digital access and infectious disease spread”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 19120.

Malamud, O, J Cristia, S Cueto and D Beuermann (2019), “Home internet access and child development: Evidence from Peru”, VoxEU.org, 8 March.

Miller, A R and C E Tucker (2011), “Can health care information technology save babies?”, Journal of Political Economy 119(2): 289-324.

Picard, L, M Pinna and C Goessmann (2022), “The impact of Fox News on the US COVID-19 vaccination campaign”, VoxEU.org, 15 April.

Valletti, T, M Nardotto, C Propper and S Amaral-Garcia (2020), “How the internet is changing the demand for healthcare”, VoxEU.org, 15 December.

Van de Poel, E, O O’Donnell and E Van Doorslaer (2007), “Are urban children really healthier? Evidence from 47 developing countries”, Social Science & Medicine 65(10): 1986-2003.