Performance pay contracts attract teachers who improve both test score and non-test score outcomes for students

Many students in developing countries experience low-quality teaching. For instance, in Pakistan, after five years of schooling, 20% of children cannot read a simple sentence or solve a two-digit subtraction problem (ASER 2019). However, there is lots of variation in teacher quality. In Pakistan, the difference between being assigned a 5th percentile teacher versus a 95th percentile teacher is a tripling in the amount of learning that takes place during the school year (Bau and Das 2020).

Schools face a challenge in identifying who will be a good teacher. The characteristics available to schools at the time of hiring, including interview scores, explain less than 5% of the variation in teacher quality (Staiger and Rockoff 2010; Rockoff and Speroni 2010). However, while employers might have a hard time knowing who is a good teacher, teachers (or potential teachers) themselves may know a lot about their own ability. Using teachers’ “private information” about their own skills could help schools identify who are the great teachers. One way to elicit this information and allow better teachers to self-select into teaching could be to offer performance incentives, which, in theory, should be more attractive to high performers. (Lazear 2000; Biasi 2021; Leaver et al. 2021; Muralidharan and Sundararaman 2011).

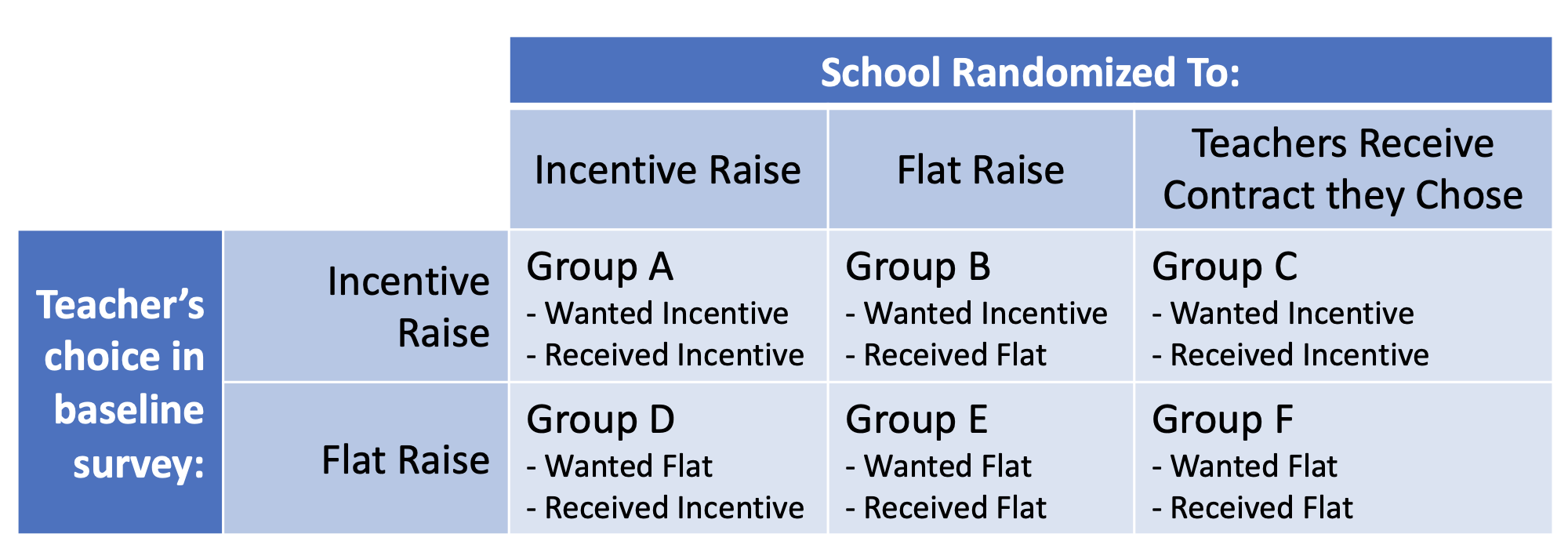

Experimental set-up: Assigning teachers to one of three contracts

In a recent study (Brown and Andrabi 2021), we test whether performance pay contracts allow schools to attract and retain better teachers. We conducted a two-year experiment with 7,000 teachers in 243 schools across Pakistan. The experiment proceeded in two phases. First, we offered teachers the opportunity to choose their contract for the coming year, selecting between a flat raise versus a performance-based raise. We let teachers know their choice would be implemented with some probability. Next, we randomly assigned schools to one of three conditions:

- Performance-based raises: Teachers received a raise, between 0-10%, at the end of the year, based on either their students’ test scores or their principals’ evaluation of them.1

- Flat raises: All teachers received a raise of 5% irrespective of performance.

- Teacher’s choice: Each teacher in the school received the contract they stated they wanted in the choice survey. The purpose of this treatment arm is to ensure that there are real stakes on the choice teachers make.

By allowing teachers to first state their preferences, we could compare the effects of being assigned a given contract overall and by what type of contract the teacher wanted. We could also see if teachers who prefer performance versus flat pay are systematically different. We group teachers into the following categories (A-F), and compare these groups along different outcomes, to test each of these questions.

Figure 1 Experimental set-up

We communicated to teachers that the contract type is associated with the school itself. This is important in this setting, as 15% of teachers transfer to work at a different school each year. We then observed what types of teachers move into schools assigned flat versus performance-raise contracts in the second year.

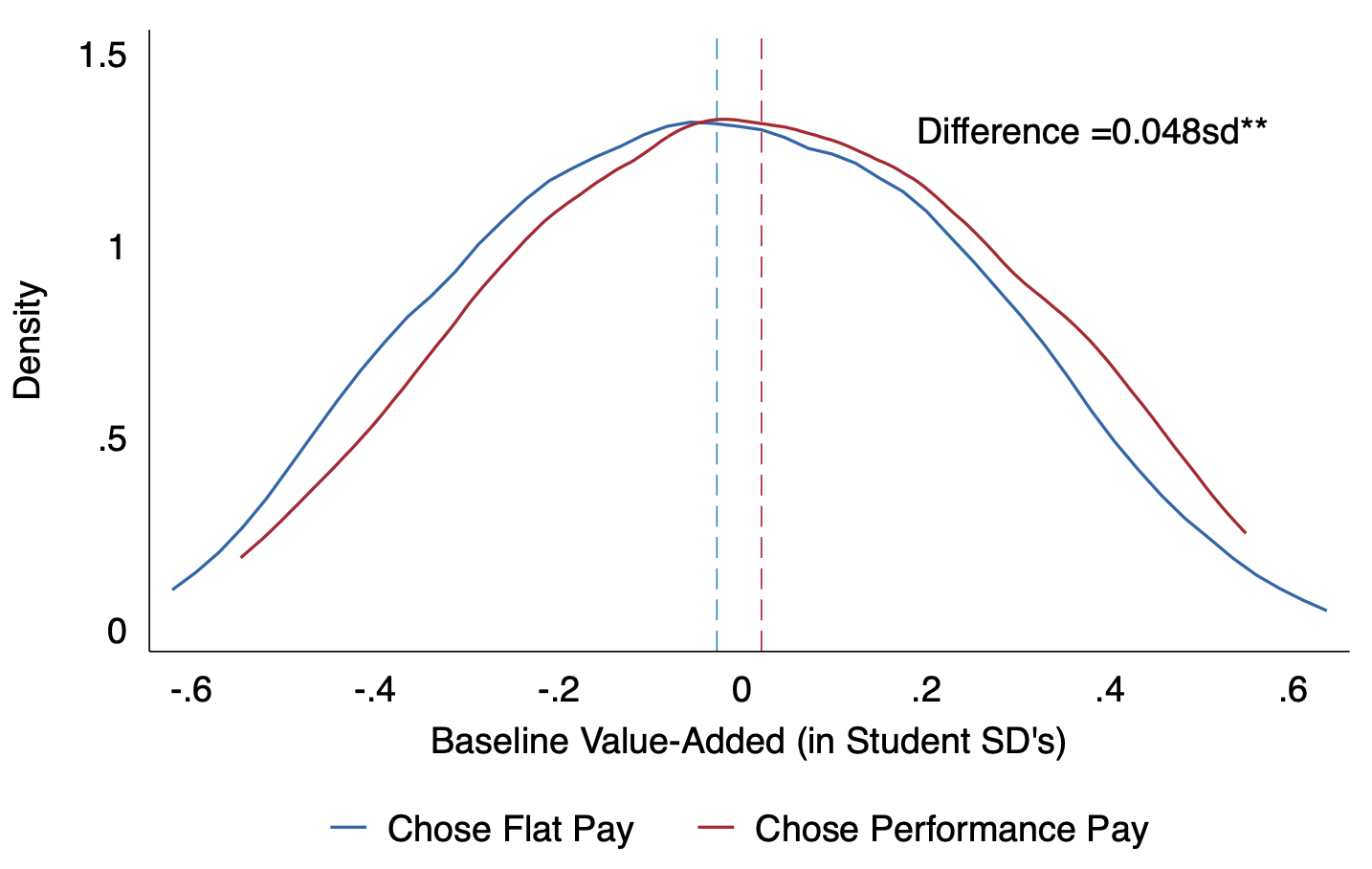

Performance pay attracts higher-performing teachers

1. We can test whether teachers who chose performance raises are systemically different. If teachers have information about how they will fair under incentives versus flat pay, then we would expect higher-quality teachers to be more likely to select performance pay. To do this, we compared teachers’ baseline performance for teachers who chose performance versus flat raises (groups A-C versus D-F). Figure 2 shows the distribution of teacher value-added2 for those who chose performance raises (red versus blue line). While we see a lot of overall variation in teacher quality, shown by the width of the distribution, high value-added teachers are more likely to select performance pay, and low value-added teachers are more likely to select flat pay.

Figure 2 Distribution of teacher value-added for teachers who chose performance versus flat pay

2. We also find that schools that are assigned performance pay attract and retain better teachers in the long run. These effects are mostly driven by high value-added teachers moving from control to treatment schools and low value-added teachers moving from treatment to control schools. High value-added teachers are also slightly more likely to leave control schools to work outside this network of schools.

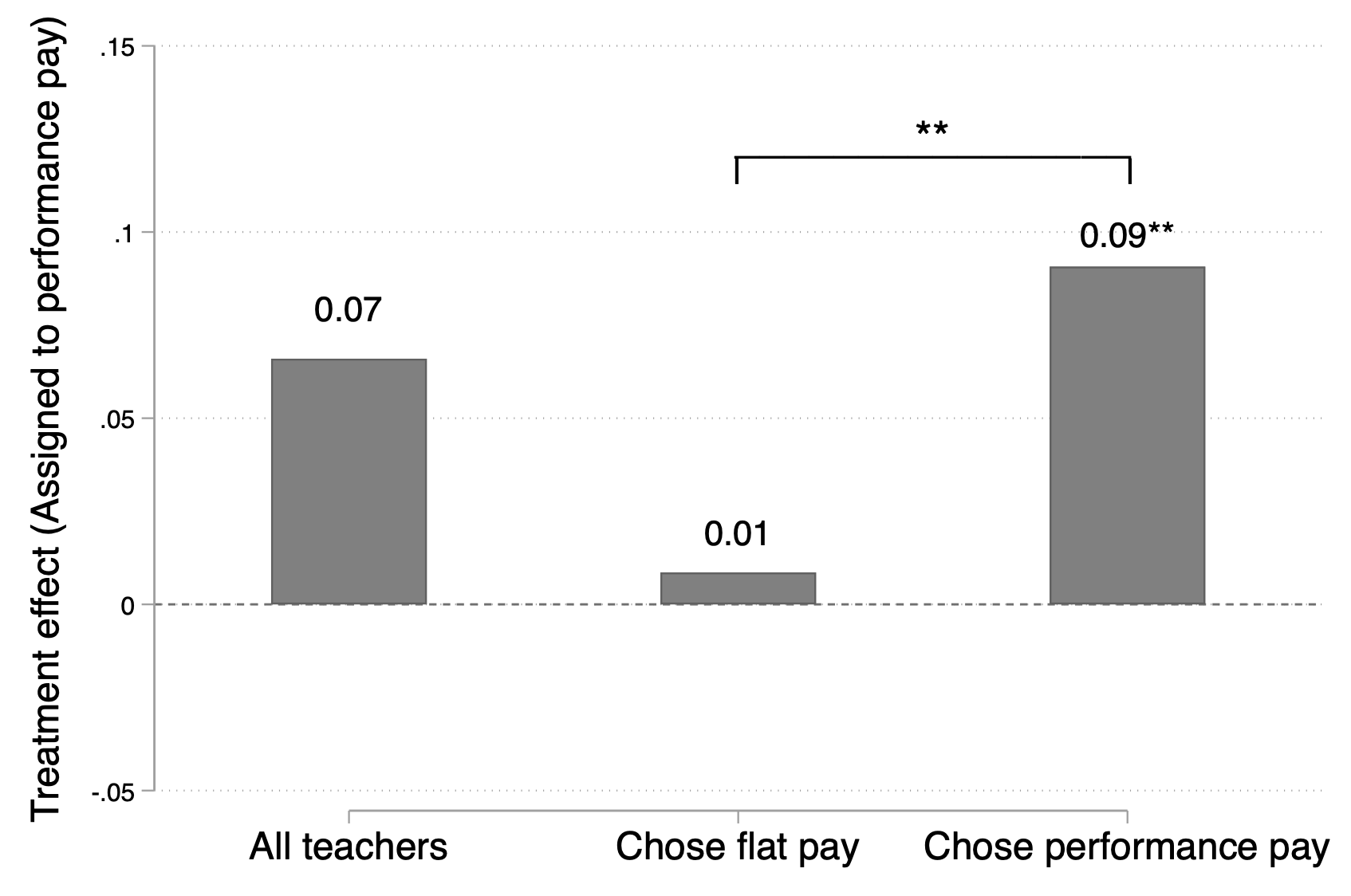

Performance pay attracts teachers who respond better to incentives

We may also expect that teachers who chose performance pay contracts “respond” better to them as well. In other words, teachers may vary in how much harder they work under incentive pay and this effort response might depend on what type of contract the teacher wanted.

To test this, we compared the effect of being assigned a performance pay contract versus a flat pay contract for teachers who wanted performance pay and for those who did not want it. Figure 3 shows the effect of being assigned a performance pay contract pooling across all teachers (the first bar), for those who wanted flat pay (group D versus E), and for those that wanted performance pay (group A versus B). Teachers who chose performance pay contracts during the baseline choice exercise have nearly nine times the effect of performance pay on test scores as compared to those who chose flat pay. This suggests, perhaps unsurprisingly, that incentives work much better for those that want them.

Figure 3 Effect of performance pay treatment on test scores by teachers’ contract preference

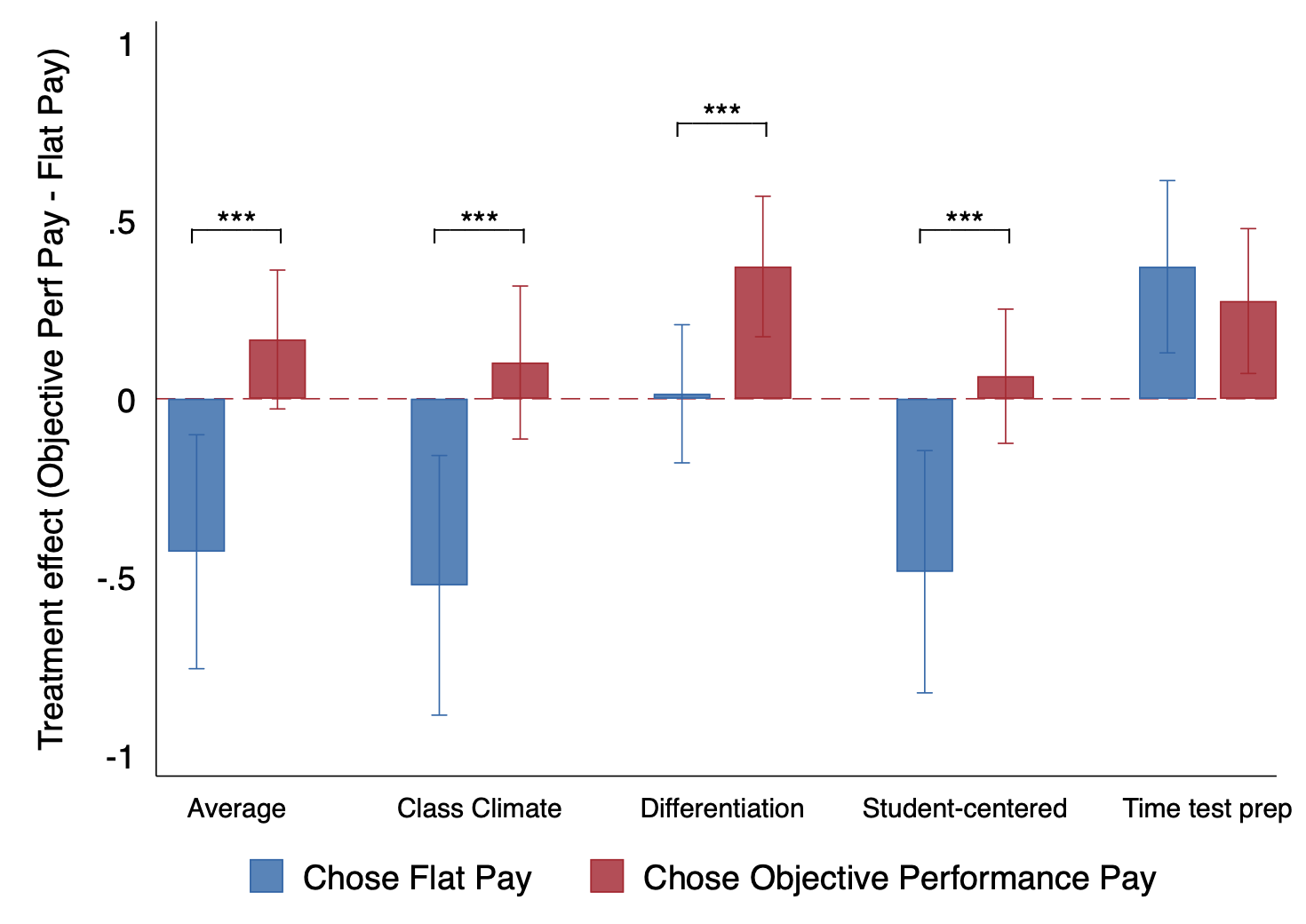

However, we might be concerned that while performance pay attracts higher value-added teachers and those who work harder in response to incentives, it also perhaps attracts teachers who intend to “game” the incentives or who are less of a team player. Encouragingly, we do not find that is the case. Teachers who chose performance pay are actually much less likely to exhibit distortionary behaviours in response to the incentives than those who chose flat pay. Figure 4 shows the effect of being assigned to a performance pay contract on a variety of teaching pedagogy. We split the sample by whether the teacher wanted performance pay or not, and we find that performance pay increases the quality of teacher pedagogy, but only for teachers who wanted the incentives. For those that wanted flat pay, incentives actually increase the likelihood that they have a bad classroom climate (things like using strict discipline) and less student-centered instruction (such as doing more lecturing instead of group work).

Figure 4 Effect of performance pay treatment on teaching strategies by teachers’ contract preference

Performance pay also increases other areas of student socioemotional development for teachers who wanted the contract. This suggests that teachers who sort in are not solely focused on maximising their salary at the cost of more well-rounded student development. Lastly, we do not find evidence that teachers who chose performance pay have other negative traits. They are actually slightly more likely to contribute to school public goods, collaborate with other teachers, and have similar levels of pro-sociality (measured using a volunteer opportunity task).

Policy implications

Combined, this evidence suggests that schools would benefit from introducing performance pay or allowing teachers to choose what type of contract they receive. Since performance pay works particularly well for those who want it, allowing teachers to choose could be both politically palatable and substantially beneficial in terms of improving student outcomes. This evidence also suggests that previous estimates of the effect of performance pay, which focus on existing teachers’ effort but ignore this sorting channel (that performance pay may attract and retain better teachers), are missing a big piece of the impact of these policies. Since the use of performance incentives for teachers has doubled globally in the last ten years (World Bank Group 2018), understanding the full effects of these policies has large-scale implications.

References

Andrabi, Tahir and Christina Brown (2021), “Subjective and Objective Incentives and Employee Productivity,” Working Paper.

ASER, (2019), Annual Status of Education Report Pakistan.

Bau, Natalie and Jishnu Das, (2020), “Teacher Value Added in a Low-Income Country”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 12(1): 62–96.

Biasi, Barbara (2021), "The Labor Market for Teachers Under Different Pay Schemes", American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 13(3): 63-102.

Brown, Christina and Tahir Andrabi (2021), "Inducing Positive Sorting through Performance Pay: Experimental Evidence from Pakistani Schools,” Working Paper.

Lazear, Edward P (2000), “Performance Pay and Productivity”, American Economic Review 90(5): 66.

Leaver, Clare, Owen Ozier, Pieter Serneels, and Andrew Zeitlin (2021), "Recruitment, Effort, and Retention Effects of Performance Contracts for Civil Servants: Experimental Evidence from Rwandan Primary Schools", American Economic Review 111(7): 2213-46.

Muralidharan, Karthik and Venkatesh Sundararaman (2011), “Teacher Performance Pay: Experimental Evidence from India”, Journal of Political Economy 119(1): 39–77.

Rockoff, Jonah E and Cecilia Speroni (2010), “Subjective and Objective Evaluations of Teacher Effectiveness”, American Economic Review 100(2): 261–266.

Staiger, Douglas O and Jonah E Rockoff (2010), “Searching for Effective Teachers with Imperfect Information,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 24(3): 97–118.

The World Bank Group, Systems Approach for Better Education Results (SABER) 2018.

Endnotes

1 In this paper, we look at the sorting response to both types of performance metrics. In a companion paper, Andrabi and Brown (2021), we separate out the differential effects of using test score-based incentives versus principal evaluation-based incentives.

2 Value-added is a measure of teacher quality that compares students of a given teacher performance on end-of-the-year tests, controlling for how the student performed at the end of the previous school year. Using value-added as a measure of teacher quality allows us to deal with the concern that some teachers may be assigned higher-performing students.