Training deputy ministers in the school of thought associated with the credibility revolution increases demand for and responsiveness to causal evidence

Improved research designs and availability of more and better data have heralded the credibility revolution in economics (Angrist and Pischke 2010). This included a shift towards randomised controlled trials (RCTs) as the ‘gold-standard’ research design and a focus on quasi-experimental methods to identify causal effects of policies.

With its careful attention to causality, the credibility revolution marks a paradigm shift in economic research, with ever greater focus put on whether a policy works or not.

Recent evidence finds that policymakers demand and even respond to evidence (Hjort et al. 2021) but are unlikely to distinguish between different types of evidence or change their policy choices when new evidence comes to light. There is an emerging consensus in the literature that policymakers are highly averse to shifting their beliefs and rather engage in motivated reasoning to justify their initial policy choices (Baekgaard et al. 2019, Banuri et al. 2019, Vivalt and Coville 2021, Lu and Chen 2021). Sticking to priors and being inattentive to evidence may stymie the implementation of good policies that might otherwise spur development (Kremer et al. 2019).

If the credibility revolution alone cannot change policymakers' receptiveness to evidence, then what can?

In a new paper (Mehmood, Naseer and Chen 2021), we test if training policymakers in the concepts associated with the credibility revolution makes them more likely to shift their initial beliefs and policy choices.

Training Pakistan’s deputy ministers

We conducted a randomised controlled trial with deputy ministers in Pakistan using Mastering ’Metrics: The Path from Cause to Effect, a prominent summary of the concepts associated with the credibility revolution, as our instrument (Angrist and Pischke 2014).

The deputy ministers first opted between high and low probability of receiving the metrics book or a self-help placebo book. We do this to elicit demand for causal thinking. The actual assignment of the book was determined by a lottery, which ensured random assignment. Our experimental design allows us to determine the causal impact of metrics training while controlling for its initial demand. The book receipt was augmented with video lectures by the authors of the books, rigorous writing assignments, presentations of key lessons learnt, and structured discussions.

The deputy ministers had to complete two high-stakes writing assignments whose grades were associated with peer recognition, cash vouchers, and their future career trajectory. The first essay required the ministers to summarise each chapter of the book, while the second asked for a discussion on how each of the chapters apply to their careers as policymakers.

The essays were rated in a competitive manner. Deputy ministers in each treatment group also participated in a zoom session to present, discuss the lessons and applications of their assigned book, followed by a structured discussion on key lessons of the book in a workshop. In the last stage of the experiment, changes in ministers’ attitudes and behaviours post-treatment are measured. This includes willingness to pay for causal evidence and response to a policy conundrum mimicking real-world policy dilemma.

Shifts in policy attitudes

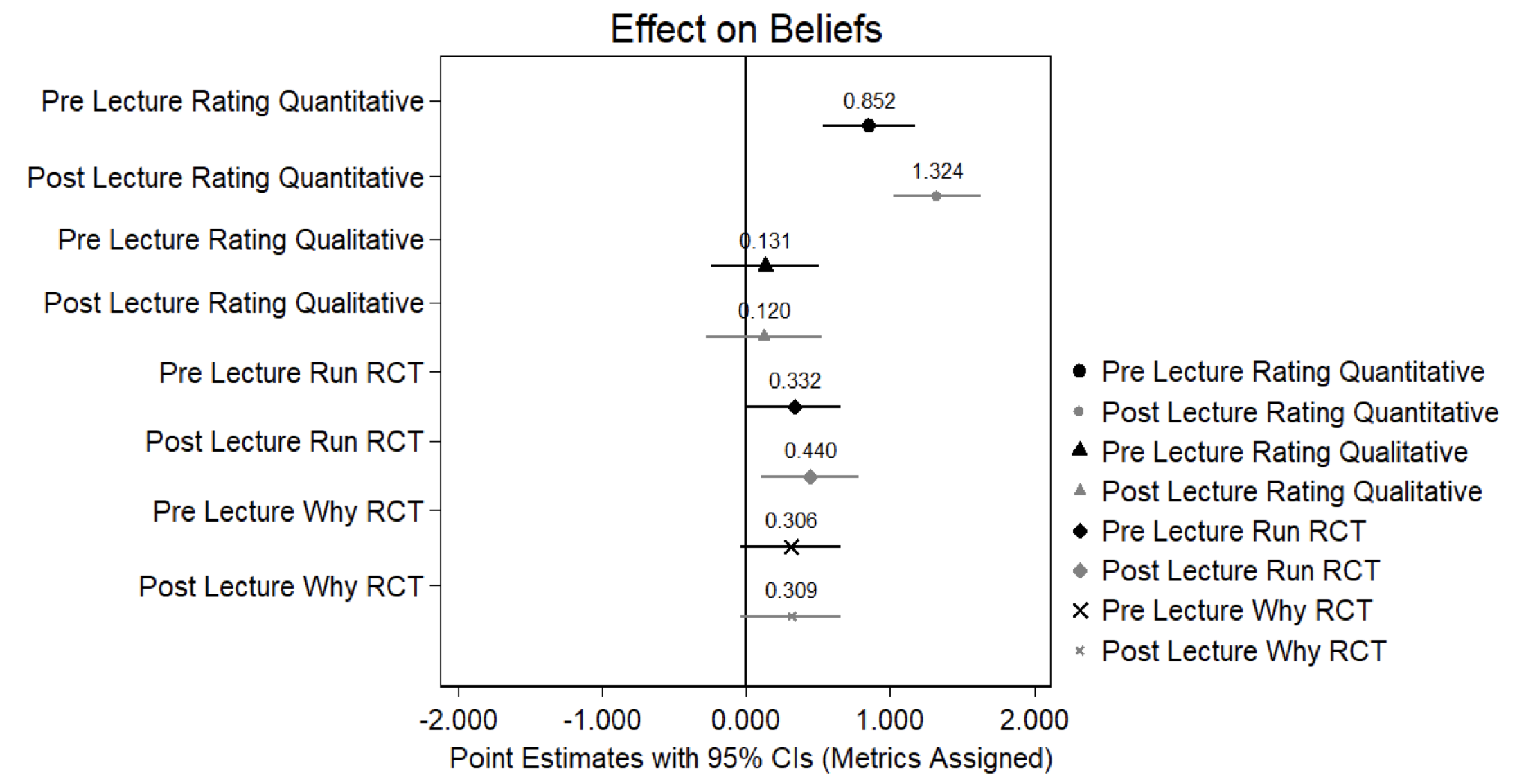

A survey conducted on the importance of quantitative evidence and causal inference six months later revealed substantial effects of the metrics training. While attitudes on the importance of qualitative evidence are unaffected, treated individuals’ beliefs about the importance of quantitative evidence in policymaking increases by 0.85 standard deviations after reading the book and completing the writing assignments and by 1.32 standard deviations after the full training of book reading, summarising each chapter, applying lessons to policy, attending the lecture, presenting, discussing, and participating in the workshop (Figure 1). This is equivalent to our metrics training increasing the importance of quantitative evidence in policymaking by 35% for partial, and 50% for the complete training.

The analysis of writings of treated deputy ministers showed an increased desire to run randomised controlled trials. They also showcased an understanding of concepts associated with the credibility revolution, using phrases such as “selection bias”, “correlation is not causation”, and “randomised evaluations allow for apples-to-apples comparisons”. We also observe substantial performance improvements in scores on national research methods and public policy assessments.

Figure 1 Impact of metrics training on beliefs

Note: The figure above estimates with the specification including choice of book and individual-level controls with all dependent variables standardised to mean zero and standard deviation one. Point estimate and 95% confidence interval on the randomly assigned metrics training is presented for each dependent variable pre and post full metrics training.

Increased willingness-to-pay for causal evidence and decrease for correlations

We then measured ministers’ willingness-to-pay for three sources of information: randomised controlled trials, correlational evidence, and expert bureaucrat advice, with the latter two being the status quo sources of information. Treated deputy ministers were willing to spend 50% more from their own pockets and 300% more from public funds for evidence in the form of randomised evaluations. In contrast, they were 50% less willing to pay for correlational evidence. Demand for senior bureaucrats’ advice was unaffected, indicating that the econometrics training did not crowd out an important input – advice by policy experts - that goes into policymaking.

Effect of causal thinking on policy decisions

To investigate the impact of the training on real world policy decisions, we elicited initial beliefs about the efficacy of a deworming policy on long-run labour market outcomes. We then asked the deputy ministers to choose between implementing the deworming policy versus building computer labs in schools. This was an actual policy decision facing ministers during the time frame of the study, making the scenario pertinent.

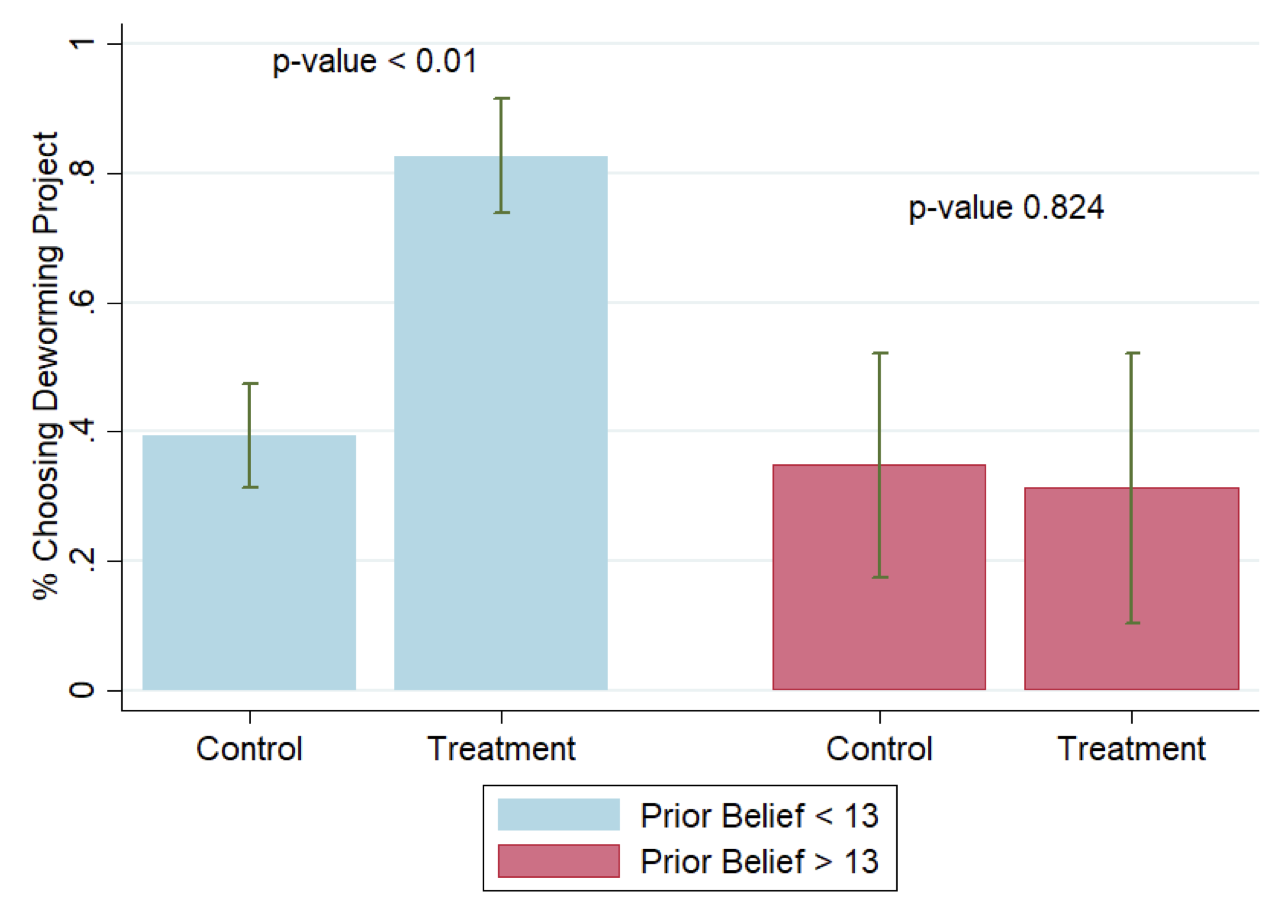

We, then, provided a signal in the form of a summary of a recently published randomised evaluation of the long-run impacts of deworming (Kremer et al. 2021). After this signal, we elicited their beliefs about the efficacy of deworming and once again asked them to make a policy choice. Only treated individuals – whose initial beliefs were less than the signal value of 13% – showed a shift in their beliefs about the efficacy of deworming, increasing their likelihood of choosing this policy from 40% to 80% (Figure 2).

This shift occurred only for those deputy ministers who estimated the efficacy to be lower than found in the study we use as the signal. Those who expected the effects to be larger did not alter their choice. However, many in the placebo group displayed confirmation bias and motivated reasoning by either updating their beliefs in the opposite direction or updating beliefs past the effect proposed by the signal.

Figure 2 Effect of metrics training on deworming project choice by initial beliefs

Note: The bar chart shows the average impact of metrics training by those that had pre-signal initial beliefs less and greater than the signal estimate of 13% impact of deworming on wages along with 95% confidence intervals.

Policy implications

Our findings suggest that training in causal thinking may increase responsiveness to causal evidence, correct for mistakes in the belief-updating process, and potentially raise welfare. By shaping deputy ministers’ causal thinking with a scalable, basic econometrics training, we show that it plays a key role for experts evaluating evidence. Those who did not receive the training did not respond to the causal evidence presented to them – neither shifting their initial beliefs nor their policy choices. Thus, the impact of the credibility revolution on policy will be muted until those in charge understand and appreciate the role causal thinking plays in evaluating evidence.

References

Angrist, J D and J S Pischke (2010), “The credibility revolution in empirical economics: How better research design is taking the con out of econometrics”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 24(2): 3-30.

Angrist, J D and J S Pischke (2014), Mastering 'metrics: The path from cause to effect, Princeton University Press.

Baekgaard, M, J Christensen, C M Dahlmann, A Mathiasen and N B G Petersen (2017), “The role of evidence in politics: Motivated reasoning and persuasion among politicians”, British Journal of Political Science 08: 1–24.

Banuri, S, S Dercon and V Gauri (2019), “Biased policy professionals”, The World Bank Economic Review 33(2): 310-327.

Hjort, J, D Moreira, G Rao and J F Santini (2021), “How research affects policy: Experimental evidence from 2,150 Brazilian municipalities”, American Economic Review 111(5): 1442-80.

Kremer, M, J Hamory, E Miguel, M Walker and S Baird (2021), “Twenty-year economic impacts of deworming”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118(14).

Lu, W and D Chen (2021), “Motivated Reasoning in the Field: Polarization of Precedent, Prose, and Policy in U.S. Circuit Courts 1930-2013”, Mimeo.

Mehmood, S, S Naseer, and D Chen (2021), “Training Policymakers in Econometrics”, Working Paper.

Vivalt, E and A Coville (2021), “How Do Policy-Makers Update Their Beliefs?”, Mimeo.