Prolonged exposure to ‘midday meals’ can improve learning outcomes on top of its other objectives

School feeding programmes provide meals to 388 million children in 161 countries, costing billions of dollars each year (WFP 2020). Improving nutrition and abating hunger are obvious rationales for these programs, but do they improve learning outcomes?

In our paper (Chakraborty and Jayaraman 2019), we study this question in the context of India’s free school lunch programme – “midday meals”. The Indian context is important for three reasons. Firstly, midday meals feed over 100 million children each school day (WFP 2020), making it the world’s largest school nutrition programme. Secondly, despite achieving near-universal primary school enrolment, India has a large learning deficit. An ASER (2005) report revealed, for example, that 44% of children between the ages of 7 and 12 who were enrolled in school could not read a basic paragraph and 50% could not do simple subtraction. Thirdly, India has some of the highest rates of malnutrition in the world and school feeding is one way to combat this. Investigating the impact of midday meals is therefore an important policy question.

The natural experiment

Simply observing that Indian children who receive midday meals do better or worse than those who do not, says nothing about the causal effect of this programme: maybe children who get midday meals do worse because governments purposefully place the programme in disadvantaged communities with worse outcomes to begin with. Or maybe children who get midday meals do better because their wealthier parents demand these programmes in schools and, because they come from better-off households, these children would have done well even without the programme.

Identifying the causal effect of this programme requires plausibly exogenous variation in programme exposure. In our study, this comes from a natural experiment which induced staggered programme implementation across time and space. In a nutshell, the Indian Supreme Court issued a directive in 2001 ordering Indian states to institute free midday meals in government primary schools. Over the subsequent five years, state governments across India introduced midday meals. Staggered implementation of the programme in primary schools generates plausibly exogenous variation in the length of potential exposure to the programme based on a child's birth cohort and state of residence. Children only enjoyed the programme to the extent that they were of primary school going age (6 to 10 years old) and lived in a state which had instituted midday meals in primary school. So, the earlier their state introduced the programme and the younger they were at the time, the longer was the child's potential exposure to midday meals, up to a maximum of 5 years.

Our data come from 2005-2012 Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) surveys. ASER administers home-based learning assessments of basic literacy (reading skills) and numeracy (number recognition and arithmetic skills) to children aged 5 to 16 in roughly 200,000 rural households across major Indian states. Our empirical specification allows for average test scores to vary across different states. This accounts for the possibility that children in better or worse performing states may have longer programme exposure because their states implemented the programme earlier or later. It also allows test scores to vary across age groups, addressing the concern that older children are likely to have higher test scores than younger children, and also potentially have longer programme exposure. Finally, the inclusion of state-specific time trends permits for trends in average test performance to vary from state to state.

Long-term exposure to midday meals increases learning outcomes

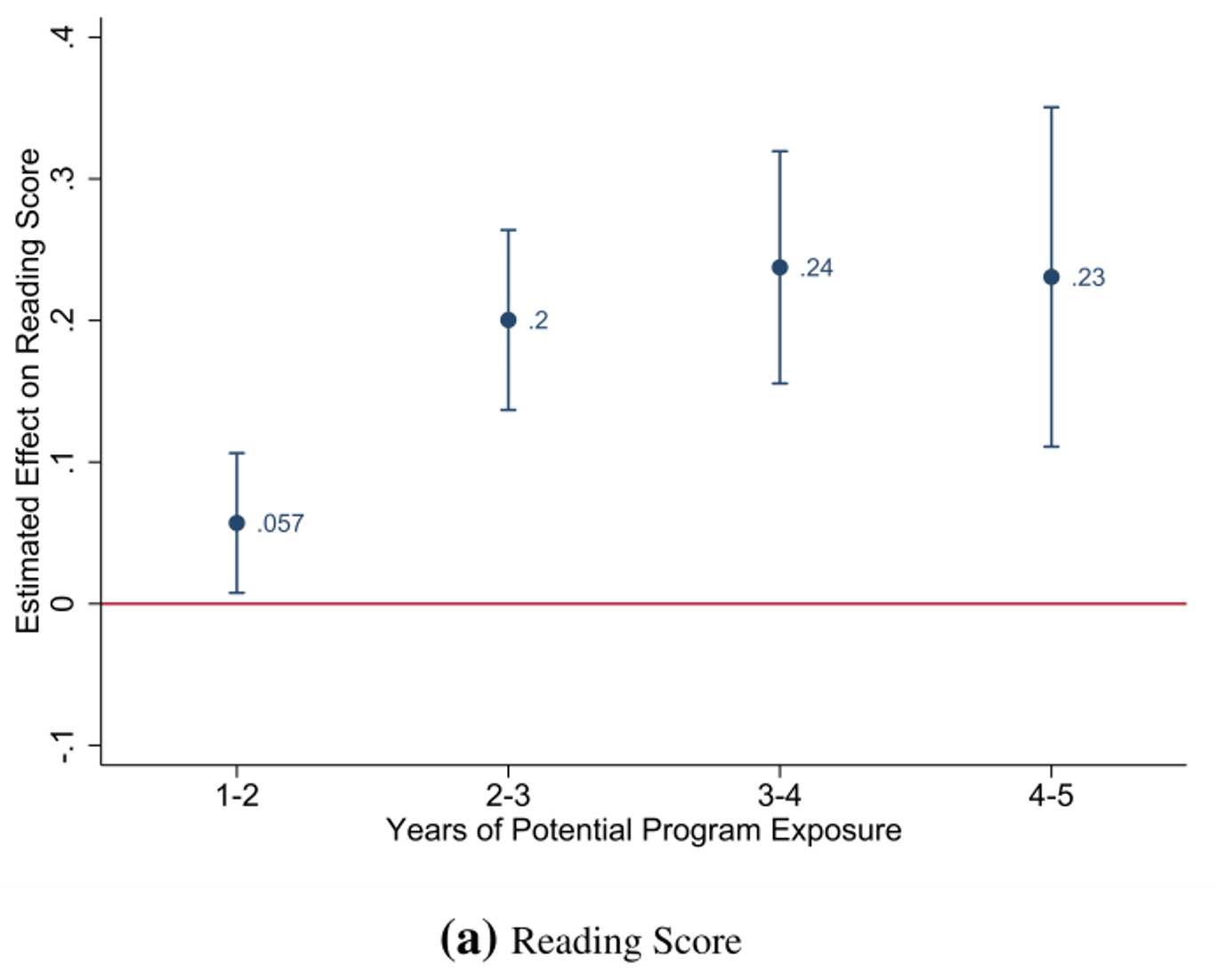

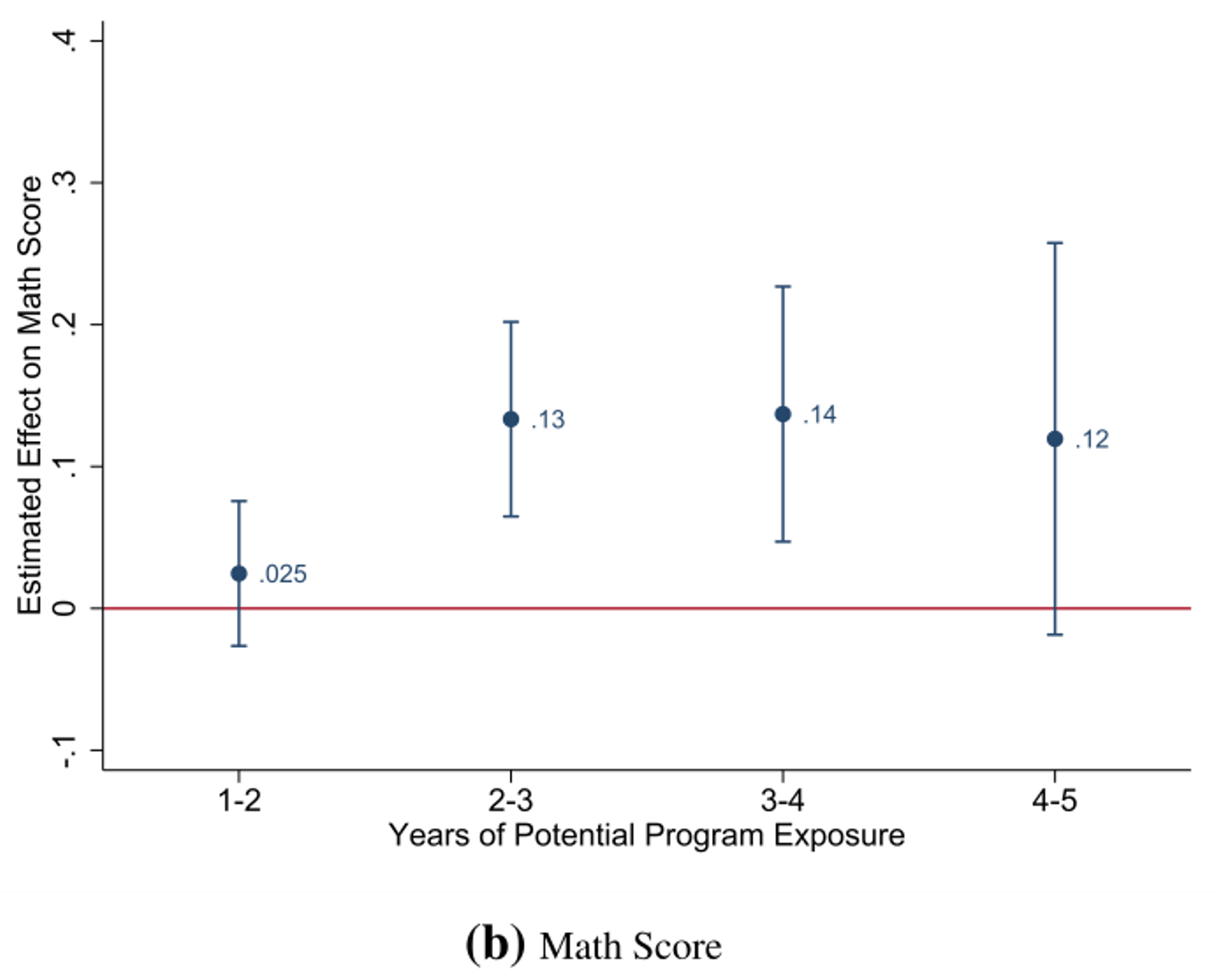

Figure 1 describes our main findings. It shows that primary school-aged children’s learning outcomes increase, albeit at a decreasing rate, with exposure to midday meals. In the second year of exposure, test scores increase by a statistically significant 0.057 points for reading. This amounts to an approximately 4.4% increase relative to the baseline (comprising children with less than 1 year of exposure). For math, the increase in test scores is half this size and statistically insignificant.

Test scores jump dramatically in the third year with a 0.20 point (15%) increase in reading and a 0.13 point (10%) increase in math, relative to the baseline. This increase in test scores from the second to the third year of exposure is not just economically, but also statistically significant. The increase jumps slightly to 0.24 (18%) for reading and 0.14 (11%) for math in the fourth year of exposure. In the final year of exposure, the effect tapers off slightly to 0.23 points for reading and 0.12 points for math.

Figure 1 The effect of midday meal exposure on test scores, by years of potential exposure

According to these estimates, a child who has been exposed to midday meals throughout primary school has reading test scores that are 18% (0.17 standard deviations) higher and math test scores that are 9% (0.09 standard deviations) higher than those of a child with less than one year of exposure. This is important in view of the negligible learning effects of school feeding programmes documented in the literature to date. In particular, the extant literature has—without exception—examined programme effects after at most two years of exposure. Our results suggest that students may need prolonged exposure to reap substantive learning benefits from the programme.

Are detractors right to worry?

The data allow us to explore three channels which speak to the concerns of those who worry that school feeding may not improve learning. The first concern is that complementary inputs are needed. Learning doesn’t miraculously emerge from food; it requires that children be taught. There is some legitimacy to this concern. We find evidence of significant complementarities with respect to those teaching inputs that are directly related to learning opportunities of children—like teacher attendance and usable blackboards—but no complementarities when it comes to general schooling infrastructure, such as having a water tap in school or the number of classrooms.

The second concern is that school feeding only benefits underprivileged children who don’t get enough food at home. If so, then the programme should benefit girls more than boys, given the well-established Indian parental preference of boys to girls, and poorer children more than wealthier. We find no evidence that this is the case but this may reflect the possibility that most of the children in this rural Indian sample (including many in the top half of this distribution) suffer from extreme nutritional disadvantage to begin with (Deaton and Drèze 2009)

The third concern is that food in the household may be redistributed away from the targeted child towards other family members, and this may temper the programme's effect on learning. We find some evidence of substitution away from potential midday meal recipients, for example, from eligible to ineligible siblings. However, even when substitution exists, redistribution is only partial. In general, benefits from the school meals stick to targeted children.

Are midday meals a cost-effective investment in learning?

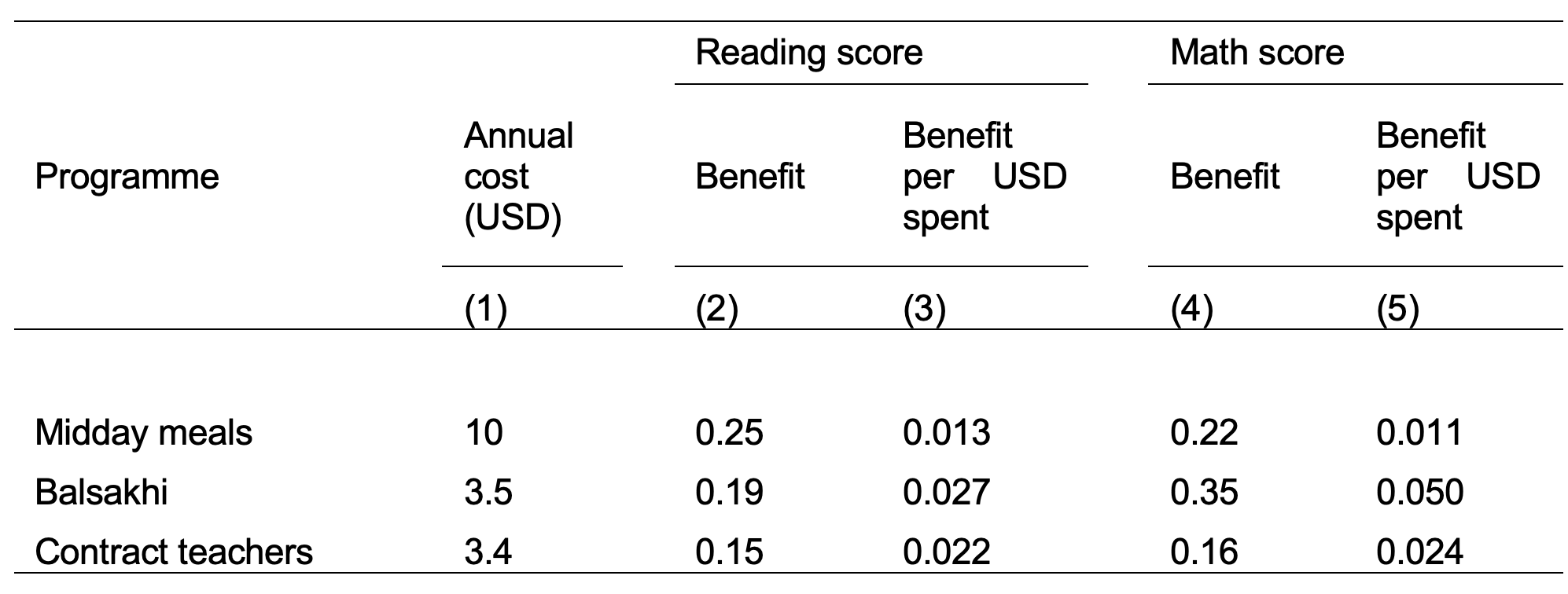

Our paper finds that long term exposure to school feeding programs leads to substantial improvements in learning outcomes. But how cost-effective are midday meals? One way to answer this question is by comparing this programme with alternative education initiatives aimed at improving test scores. Table 1 makes this comparison with two such interventions, both of which ran in India for two years. In the first—“Balsakhi”—weaker children in third and fourth grades were taught for two hours during school time by local women, thus receiving more personalised attention (Banerjee et al. 2007). The second is the appointment of contract teachers, which reduced pupil-teacher-ratios in public schools (Muralidharan and Sundaraman 2013).

Table 1 Comparing midday meals with other learning programmes

Column 1 shows that, at US$10 per child per year, midday meals are almost three times as costly as the other two programmes. This is not surprising: meal costs rise with the number of individual beneficiaries whereas teachers address groups of students. At the two-year mark, midday meals’ reading benefits (column 2), though higher, don’t make up for its higher costs. Thus, in terms of reading benefit per dollar spent (column 3), it is only half as cost effective. In terms of math performance (column 4), midday meals do better than contract teachers but worse than Balsakhis. But again, because meals are so much more costly, they fare worse than the other two programmes from a benefit-cost perspective (column 5).

In terms of bang for buck in learning outcomes, the other two programmes thus seem like a better investment. Then again, the aim of the midday meal programme was to improve nutrition and not learning. Viewed in this light, the programme's learning benefits seem rather remarkable.

References

ASER (2005), Annual Status of Education Report, Technical report, ASER.

Banerjee, A V, S Cole, E Duflo, L Linden, et al. (2007), “Remedying education: Evidence from two randomized experiments in India”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(3): 1235–1264.

Chakraborty, T, R Jayaraman (2019), “School feeding and learning achievement: evidence from India's midday meal program”, Journal of Development Economics, 139: 249-265.

Deaton, A and Drèze (2009), “Food and nutrition in India: Facts and interpretations”, Economic and Political Weekly, 14: 42–65.

Muralidharan, K and V Sundararaman (2013), “Contract teachers: Experimental evidence from India”, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 19440.

World Food Program (WFP) (2021), State of School Feeding Worldwide, 2020 Report.