The emergence of ready-made-garment sectors in poor countries can have substantial impacts on women’s health and decision-making power

The importance of manufacturing to national incomes in Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa has increased substantially since the 1990s (Kruse et al. 2022). In some sub-sectors, such as the production of ready-made garments (RMG), women comprise the overwhelming majority of workers (Hossain and Bank 2012, Davoine 2021). For many of these women, the only alternative employment would have been in small-scale agriculture. Despite these large recent changes in the opportunities facing women in poor countries, there remains a dearth of literature identifying the impacts of manufacturing work on the agency of women. Doing so is of potential importance to efforts aimed at the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly those pertaining to poverty reduction, gender equality, and decent work and economic growth. Increased control over income is likely important to a woman’s ability to make decisions about her health and about the allocation of incomes to different items for household consumption.

Ready-made garment (RMG) exports grew rapidly in Lesotho after the signing of the US African Growth and Opportunities Act (AGOA) in May 2000 (Dowlah 2016). This preferential trading agreement simultaneously created strong incentives for large-scale foreign direct investment in garment manufacturing facilities, and for national governments to invest in the new infrastructure necessary to host industrial zones. By 2012, Lesotho had become the largest Sub-Saharan African (SSA) exporter of garments to the US (Central Bank of Lesotho 2011).

The little evidence detailing the impact of women’s employment in manufacturing on their decision-making power in households is encouraging. Heath and Mobarak (2015) find that children obtain more schooling when employment opportunities for RMG increased in Bangladesh. Women marry later and also delay childbearing. These findings are consistent with earlier descriptive studies for South Asia. Amin (2006) finds similar results in a comparative case study of Bangladesh, Vietnam and Egypt. While White et al. (2001) partly attribute the fertility decline in Vietnam since the 1980s to the industrialisation policies pursued under the Doi Moi programme of reforms.

New jobs for women in Lesotho

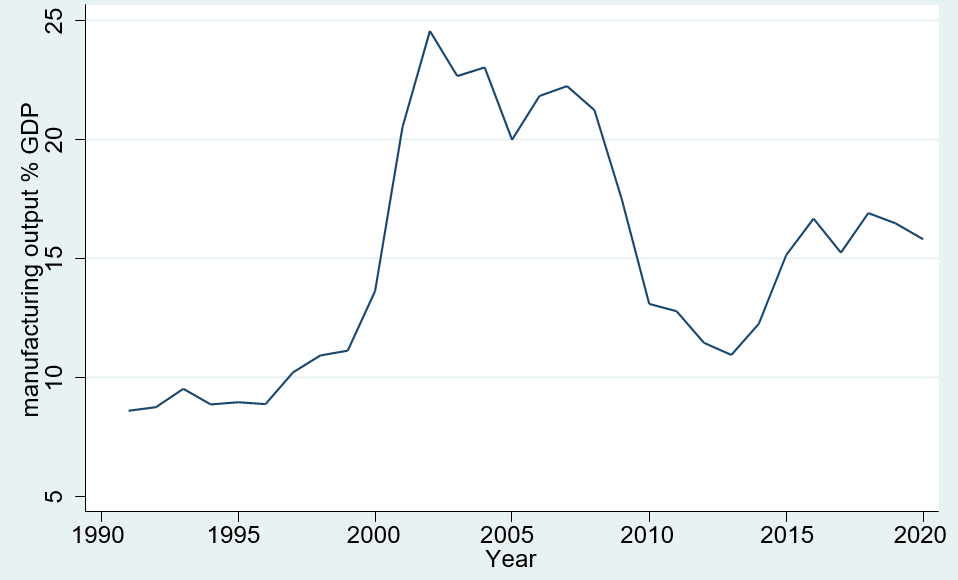

The share of GDP from manufacturing rose from less than 10% in 1990 to nearly 25% by the year of the first available DHS survey in 2004 (shown in Figure 1). This sector comprises food products and beverages, textiles, clothing, footwear and leather, and other manufacturing. The orientation of textile production towards the US market is unique amongst Lesotho’s industries as much of the non-textile exports of the country go to South Africa.

Figure 1: Manufacturing output as a percentage of GDP, Lesotho (1990 - 2020)

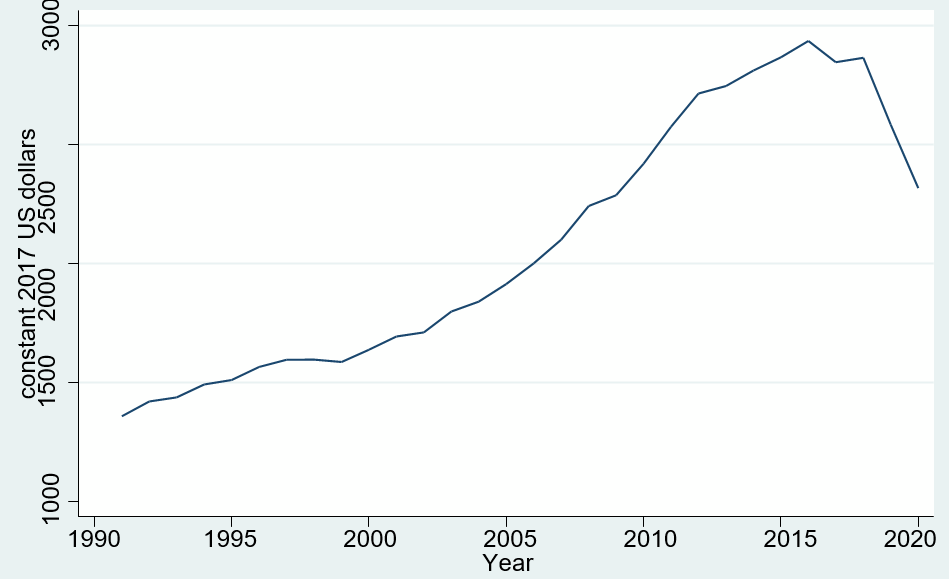

Coincident with the GFC and phase-out of the MFA, the contribution of manufacturing to GDP fell steeply during 2008-10. By 2014, this share was still below the 2004 level, about 12%. as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Real GDP per capita at purchasing power parity, Lesotho (1990 - 2020)

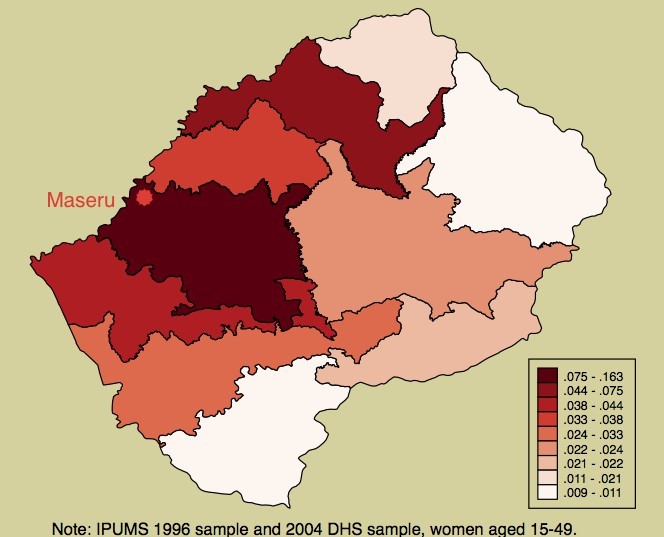

The greatest increases in RMG employment during 1996-2004 occurred in Maseru and neighbouring districts with good road access to the railhead to South Africa. These are districts containing post-AGOA industrial zones: Leribe, Mafeteng and Mohale’s Hoek as illustrated in the map of Figure 3. Maseru district, which also contains the Thetsane industrial zone, is represented in the deepest red colour. In the mountainous and remote districts most distant from Maseru, RMG employment essentially did not increase after AGOA and no industrial zones were constructed in these districts. The geographic distribution of industrial zones suggests that new job opportunities for women under AGOA and the effects of the post-2008 shock would be geographically heterogeneous.

Figure 3: Increase in RMG employment by district of Lesotho, 1996-2004

Is Lesotho typical?

Wages and working conditions in the RMG sector are strongly regulated in Lesotho and a child labour ban is enforced by the government. RMG sector workers are also generally unionized, and may have access to on-site childcare and healthcare (Gibbon 2003). Factories operating in industrial zones pay much higher wages both relative to local alternatives and relative to those paid in other RMG host countries including Vietnam and Bangladesh. In 2007, the average monthly earnings of an employee in the RMG sector was US$103, and the minimum monthly earnings for a general textile worker in Lesotho was $93 (RMG Bangladesh 2016). In 2007, annual GDP per capita was far lower at $846 in current US dollars, a monthly equivalent of $71 (World Bank 2022). Still, production costs were internationally competitive in the early 2000s. Eifert et al. (2005) calculated the labour costs per shirt produced in Lesotho in 2004 as $0.19 in current US dollars, far under the $0.65 for South Africa and $0.29 for export processing zones in China. By August 2018, the minimum monthly earnings for a textile worker had risen to $138 (Al Mahfuz 2018).

Are RMG workers typical?

Well-paid, reliable RMG work in formal workplaces may have very different impacts on decision-making power and health than the major alternatives, subsistence agriculture and informal services (Mammen and Paxson 2000). In Lesotho, RMG work is associated with increased decision-making power for women in their households. Data from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) (over the years 2004, 2009 and 2014) reveals that women engaged in RMG work reported considerably more say in decisions for all outcomes save for “large purchases”. In the absence of wage, household consumption, or time use data, subjective responses may provide a measure of the impact of RMG employment on women’s ability to direct household resources to their priorities.

There are substantial differences between women engaged in RMG work and others in their fertility and health behaviours. Economic theory suggests several channels through which fertility might fall with higher potential wages. The opportunity costs of home production, in which children are intensive, rise as the labour market opportunities of women increase (Becker 1965). DHS data also shows that the RMG-employed are much less likely to have a child born in the preceding two years and are also much more likely than others to currently use effective contraception, defined by DHS staff as using either IUDs, condoms, the pill, and foam or jelly.

In the DHS, women are asked to report the acceptability of a partner beating his wife in five different hypothetical situations. The responses suggest that a woman’s decision- making power in her relationship might be substantially improved by RMG work. Comparing responses across RMG- and non-RMG-employed women shows that in all of the five hypothetical situations considered in DHS interviews, women are significantly less likely to report that they find beating acceptable if employed in the RMG sector.

Causal effects

Clearly, RMG workers may differ from others in Lesotho in ways that are correlated with their answers to survey questions. However, the data also permits identification of causal impacts. The post-2008 shock to the employment of workers in this sector is exploited to identify the impact of this work on women’s say in household decisions, health, fertility, and attitudes to violence from partners. In Grogan (2023), variation in RMG employment propensities from the combination of distance between a woman’s residence and the nearest industrial zone, and from the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) demand shock, creates a natural experiment. The combined shocks to textile demand from the US during the 2008-09 GFC, and the gradual phase-out of the Multi-Fibre Agreement together resulted in a large, temporary, decline in RMG employment. Women who reside closer to potential RMG employment are more likely to work in the sector and are also more likely to be impacted by a trade shock.

The combined 2004-2014 DHS data suggest several impacts of RMG employment on living standards. No direct impact of industrial zones on men’s employment is detectable in the survey data. However, RMG work appears to change the opportunity cost of time spent raising children, to improve reproductive health, to significantly increase women’s say in household resource allocation, and to reduce acceptance of spousal violence. These findings suggest that the well-paying RMG jobs which resulted from AGOA may have profound long-term economic and cultural effects.

The findings demonstrate how important government policy can be for harnessing new trade opportunities, but also the sensitivity of wellbeing gains from RMG work to trade shocks. Diversification of manufacturing to other products and markets may offer host economies greater insulation against global demand shocks. The opportunity for Lesotho and other countries with RMG sectors may already have arrived. As many companies search for new factory locations outside of China, industrial zones originally set up under AGOA for RMG factories could be attractive choices. The new jobs created could potentially reduce poverty more permanently, and at less cost, than social welfare programmes funded by taxes or development aid.

References

Al Mahfuz, M (2018), “Sourcing costs climb due to minimum wage upsurge”, Textile Today Bangladesh (Accessed December 6th 2021).

Amin, S (2006), “Implications of trade liberalization for working women’s marriage: Case studies of Bangladesh, Egypt and Vietnam”, Trading Women’s Health and Rights: Trade Liberalization and Reproductive Health in Developing Economies, :97-120, Zed Books, New York.

Becker, G (1965), “A theory of the allocation of time”, The Economic Journal 75(299): 493–517.

Central Bank of Lesotho (2011), Africa growth and opportunities act (AGOA): Economic impact and future prospects, www.centralbank.org.ls (Accessed January 28th 2022).

Davoine, D (2021), Gearing up for more women leaders in the garment sector in Vietnam, World Bank blog.

Dowlah, C (2016), International trade, competitive advantage and developing economies: How less developed countries are capturing global markets, New York: Routledge.

Eifert, B, A Gelb, and V Ramachandran (2005), “Business environment and comparative advantage in Africa: Evidence from the investment climate data”, The World Bank.

Gibbon, P (2003), “AGOA, Lesotho clothing miracle and the politics of sweatshops”, Review of African Political Economy 30(96): 315-350.

Grogan, L (2023), “Manufacturing employment and women’s agency: Evidence from Lesotho 2004-2014”, Journal of Development Economics 160: 102951.

Heath, R and M Mobarak (2015), “Manufacturing growth and the lives of Bangladeshi women”, Journal of Development Economics 115: 1–15.

Hossain, N and W Bank (2012), “Exports, Equity, and Empowerment: The Effects Of Readymade Garments Manufacturing Employment On Gender Equality In Bangladesh” World Bank.

Kruse, H, E Mensah, K Sen, and G de Vries (2022), “A manufacturing (re)naissance? industrialization in the developing world”, IMF Economic Review 183 (7).

Mammen, K and C Paxson (2000), “Women’s work and economic development”, The Journal of Economic Perspectives 14(4): 141–164.

RMG Bangladesh (2016). Beyond the horizon: Lesotho and its readymade garment industry. rmgbd.net (Last accessed December 12th 2021).

White, M, Y Djamba and D Nguyen Anh (2001), “Implications of economic reform and spatial mobility for fertility in Vietnam”, Population Research and Policy Review 20:207–228.

World Bank (2022), World bank development indicators. GDP per capita current usd Lesotho.