On average, Special Economic Zones in China increased local high school enrolment rates, but this masks varying impacts between different types of zones

Special Economic Zones (SEZs), which are geographically defined areas where incentives and infrastructure support are provided to boost industrial activities, have been widely implemented by governments worldwide for decades. It has been recognised that SEZs serve as growth engines in targeted areas through attracting investment and generating agglomeration economies, i.e. the benefits which arise when firms and people locate near one another (for a review, see Austin et al. 2018, Neumark and Simpson 2015).

SEZs can also have direct impacts on the job market in a particular region (The Economist 2015), but their effect on local human capital investment is rarely examined. Literature on trade and development economics suggest that SEZs may have varying impacts on human capital investment depending on the type of industry they promote. For example, Atkin (2016) finds that the growth of export manufacturing in Mexico is associated with a decline in educational attainment. Oster and Steinberg (2013), however, find that job growth in the IT service sectors has led to higher school enrolment. To reconcile these mixed results across studies, we examine whether SEZs in China affect local educational attainment differently depending on which industry they promote (Lu et al. 2023).

Special Economic Zones in China

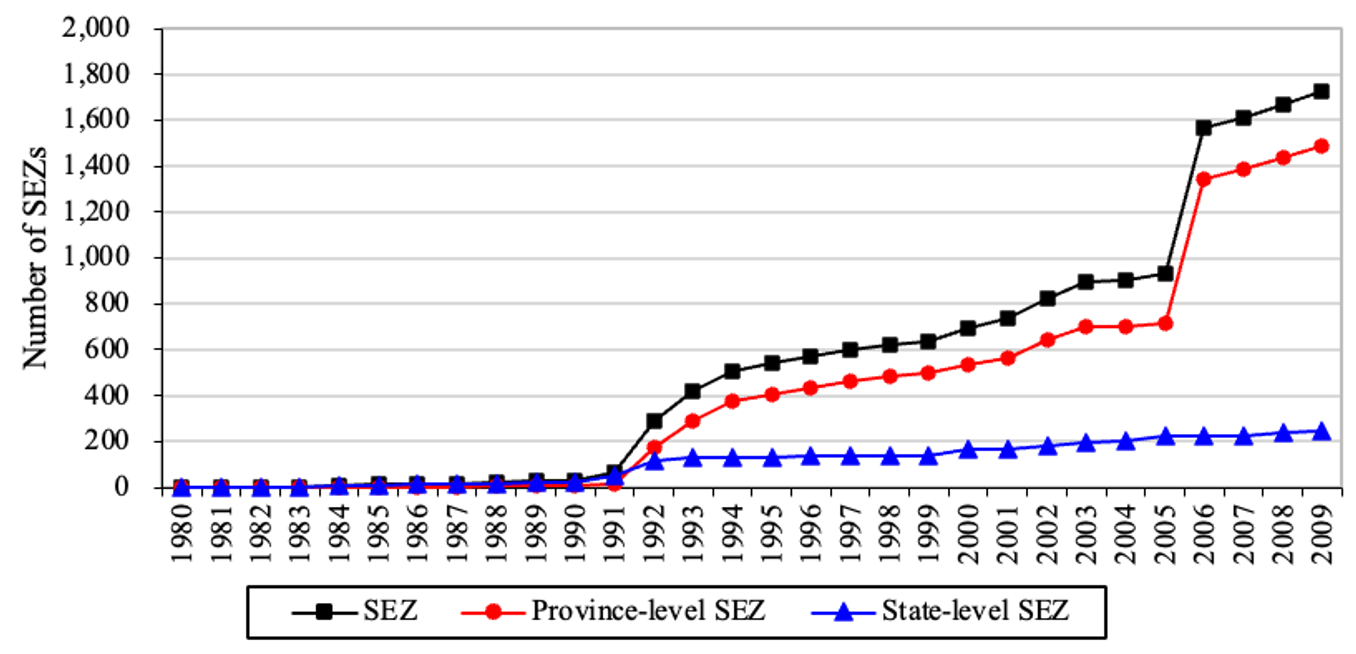

The first modern SEZ was established in Ireland in 1959, but the popularity of SEZs grew in the 1980s when China embraced this idea to introduce modern technology, pilot reforms and drive export growth. By 2010, China had established more than 1,600 SEZs at state and provincial levels. Figure 1 illustrates the trends of these SEZs, which reveals an increase in the number of SEZs over time, especially those established by provincial governments. The SEZs in China have contributed significantly to local economies despite the high costs associated with infrastructure investment, as well as the loss of tax revenues. For instance, between 1980 and 1984, the first group of cities hosting state-level SEZs achieved significant economic growth, with Shenzhen's GDP growing at 58% annually, Zhuhai's at 32%, Xiamen's at 13%, and Shantou's at 9% (Zeng 2015). As well as having a large number of SEZs, China also has different types of zones with a variety of economic focuses. For example, in order to foster technology-based innovation and high-tech industrialisation, technology-oriented SEZs (technology SEZs) have been set up, including economic and technological development zones (ETDZs) and high-tech industrial development zones (HIDZs). At the same time, China has established many export-led SEZs, such as export-processing zones (EPZs), containing labour-intensive sectors and serving as export processing sites.

Figure 1: The trends in the number of SEZs, 1980–2009

The effect of SEZs on local high school enrolment rate

Using geocoded data of SEZs combined with population census information, we investigate how SEZs affected high school enrolment at the county/district level in China over a span of more than 30 years. Whether students enrol in high school constitutes an important investment decision, since they are not legally obliged to attend and could instead choose to work.

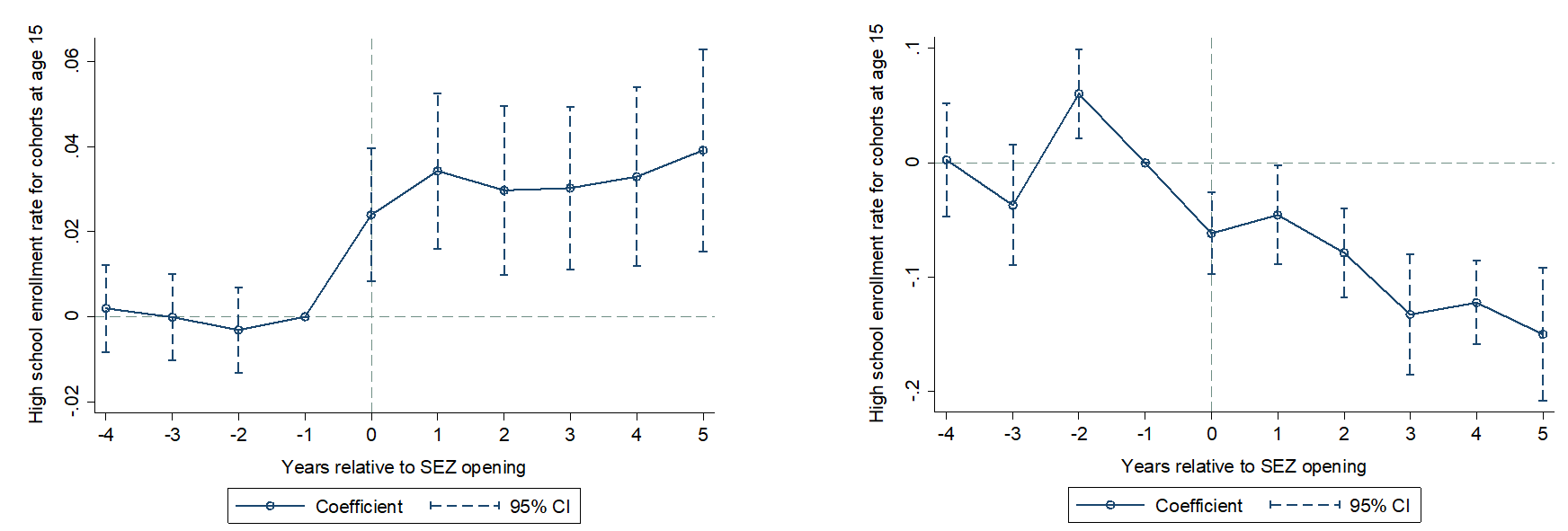

Comparing, by county, cohorts exposed to SEZs at 15 years old and those not exposed to SEZs reveals a positive impact of SEZs on the local high school enrolment rate. According to our estimates, 31 additional students are motivated to enrol in high school if an SEZ existed in their local area when they finished middle school, at approximately 15 years of age. We find, however, that the effects of SEZs vary depending on their type: technology-oriented zones encourage education, while export-led zones discourage it. Figure 2 displays the estimated impact of each type of SEZ on high school enrolment, before and after treatment, which illustrates these differing effects. The post-treatment estimates in Panel (a) show a pronounced upward trend in the effect of technology SEZs while in Panel (b), we observe a dramatic decline in the impact of export SEZs.

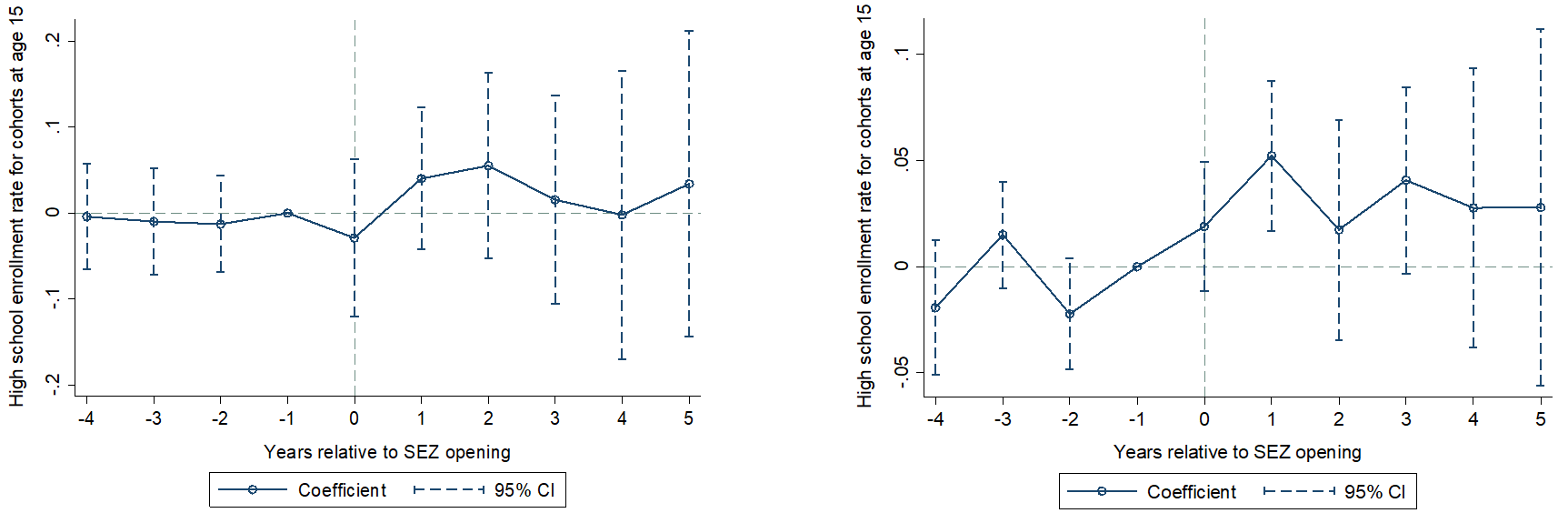

Figure 2: Event studies: The effects of different types of SEZs on high school enrollment rates at age 15

a. Technology SEZs b. Export SEZs

c. Border SEZs d. Other SEZs

Notes: Technology SEZs, Export SEZs, Border SEZs, and Other SEZs are technology-oriented zones, export-led zones, border related zones, and zones in the other category, respectively. Each figure plots the coefficients of estimates based on event study analysis along with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals.

What can explain such heterogeneous effects?

SEZs may affect educational choices through two theoretical perspectives that are not mutually exclusive: one treats schooling as a consumption good and the other views education as an investment (Becker 1964). In the former theory, households benefit from consumption, and therefore an increase in household income will allow a household to consume more of all goods, including education. In the latter investment theory, a person's choice of education depends on the trade-off between long-term educational benefits and short-term costs. Thus, three possible channels may influence a person's educational choice under these two theoretical perspectives: 1) income, 2) employment opportunities, and 3) wage premiums (i.e. how much schooling increases wages).

Our mechanism analysis shows that the high school enrolment rate in SEZs significantly increases with the number of newly available and existing jobs requiring high school education. Meanwhile, the enrolment rate decreases when there are more jobs requiring middle school graduates or lower. These two findings are consistent with job opportunity channel whereby the educational requirements of local employers shape student’s investment decisions. We also find that a larger wage premium for high school graduates in SEZs encourages high school enrolment, while higher premiums for those with middle school education discourage it. This finding confirms the wage premium channel is also at play. Furthermore, we find that a very small share of the treatment effect can be explained by the income channel. Therefore, we show that the overall impact of SEZs on education is primarily determined by the relative magnitude of the job opportunity channel and the wage premium channel.

Policy implications

Our analysis shows that SEZs have had systematic impacts on human capital development in China. The positive average effect of SEZs we find suggests an alternative way in which SEZs may generate long-run economic gains, through increased human capital investment. However, this effect is contingent on the types of industries SEZs seek to promote, and the negative impact we find for the job opportunities and wage premiums of middle school or below educated workers, particularly in export-led SEZs, calls for caution. To mitigate this, governments may consider providing financial support to students enrolling in high schools, or increasing the costs of recruiting middle school graduates.

References

Austin, B, E Glaeser, and L H Summers (2018), "Saving the Heartland: Place-Based Policies in 21st Century America," Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 8.

Atkin, D (2016), "Endogenous Skill Acquisition and Export Manufacturing in Mexico," American Economic Review, 106 (8): 2046-85.

Becker, G (1964), "Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis with Special Reference to Education," New York: Columbia University Press.

Lu, F, W Sun, and J Wu (2023), "Special Economic Zones and Human Capital Investment: 30 Years of Evidence from China," American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, Forthcoming.

Neumark, D, and J Kolko (2010), "Do Enterprise Zone Create Jobs? Evidence from California’s Enterprise Zone Program," Journal of Urban Economics, 68:1-19.

Oster, E, and B M Steinberg (2013), "Do IT Service Centers Promote School Enrollment? Evidence from India," Journal of Development Economics, 104: 123-135.

The Economist (2015), "Special Economic Zones: not so Special," April 4th edition. Available online at https://www.economist.com/leaders/2015/04/04/not-so-special

Zeng, D Z (2015), "Global Experiences with Special Economic Zones: Focus on China and Africa," Policy Research Working Paper, No. 7240. World Bank, Washington, DC.