Stereotyped assessments by teachers exacerbate gender disparities in educational outcomes for high school students in Peru. New evidence shows that these negative impacts persist years later in labour market gender gaps.

Gender gaps in employment and education have declined more quickly in high-income countries than middle- and low-income countries. The equalising effects of tertiary and secondary education in developing countries are constrained due to structural limitations that significantly hinder women’s workforce outcomes (World Bank 2012). In addition, anti-discrimination laws are either more recent, or less rigorously enforced, compared to those in developed countries (World Bank 2022).

Although a large body of research shows that educators have a lasting impact on their students’ careers long after they leave the classroom (Chetty et al. 2014a, 2014b, Rothstein 2010, 2017), less is known about their role in perpetuating gender pay and employment gaps. On the other hand, there is new research exploring the causes of gender gaps in adulthood (see, for instance, Rousille 2021, Exley and Kessler 2022, Coffman 2014, Le Barbanchon et al. 2020, Biasi and Sarsons 2020, Niederle and Vesterlund 2007). In my research (Martinez 2022), I expand and connect both research areas by examining the extent to which gender-stereotyped teacher assessments regarding students’ abilities affect their labour market outcomes and educational careers.

Measuring teachers’ stereotypes in Peruvian schools

My study uses novel data from two sources: linked administrative information containing students’ academic and professional trajectories from ages 12 to 22 and nationwide survey responses from teachers and students in Peruvian public high schools.

Using students’ grades from eighth through twelfth grade, I measure teachers’ stereotypical assessments by examining the differences in gender gaps between teacher-assigned and standardised assessments. This approach ensures that any remaining gender differences in classroom evaluations are reflective of teachers’ stereotypical beliefs of students’ abilities in subjects like maths and language arts. The data reveals underlying stereotypes in how teachers evaluate numerical and communication skills when they know the gender of the test-taker.

In addition to the administrative information needed to construct a measure of grading-based stereotypes, collected information on implicit gender biases through the Implicit Association Test (IAT). Higher positive IAT values indicate stronger gender stereotypes against girls in maths, as they reflect a stronger association of girls with language arts and humanities, and boys with maths and science. In contrast, negative IAT values suggest the opposite: stronger stereotypes favoring girls in maths and science. According to the authors of this test, scores above 0.35 in absolute value indicate a moderate to severe implicit bias, values between 0.15—0.35 in absolute values indicate a slight implicit bias and values between -0.15 and 0.15 indicate no implicit bias against girls.

In partnership with the Ministry of Education of Peru, I co-developed a government educational portal for teachers and students. Through this platform, both teachers and students participated in an Implicit Association Test - linked surveys that were designed to capture implicit stereotypes. This novel dataset contains responses from 2,500 teachers and more than 5,100 student responses. Eventually, a subset of this data was included in the analysis because it managed to be linked with the administrative data.

Figure 1: Students performing the test in Peru

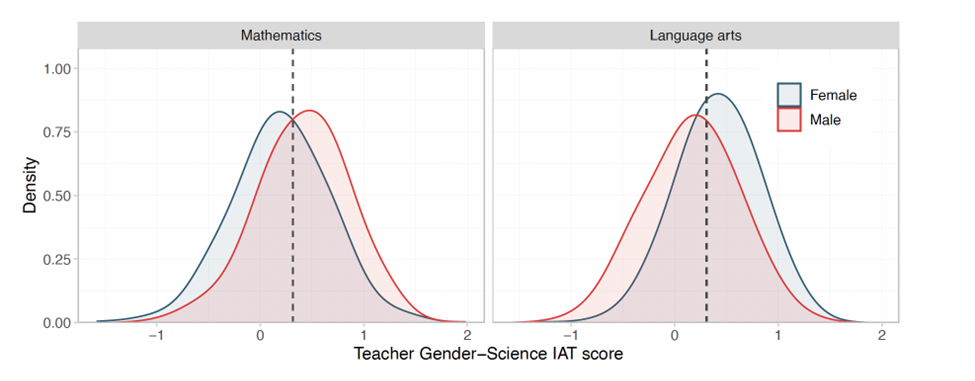

Figure 2: Distribution of teachers’ gender-science Implicit Association Test scores

Figure 2 shows the Implicit Association Test score distribution for educators in the study sample. Similar to Carlana’s (2019) findings for Italian maths teachers, the maths instructors in this sample have an average score of 0.32, while language arts teachers average 0.31 on their score, disfavoring girls in maths. These Implicit Association Test scores indicate that teachers in these main high school subjects exhibit gender stereotypes about abilities that are congruent with the student’s gender.

When examining the relationship between the Implicit Association Test and the grading-based stereotypes measure, I find that teachers who perceive boys as better than girls in math- and science-related fields (according to the IAT) tend to give boys higher grades than deserved in mathematics, while giving girls lower grades than deserved. Moreover, teachers who perceive girls, according to the IAT, as more competent in language arts award them higher grades in this subject. These findings provide supporting evidence that gender-based grading differences meaningfully reflect stereotypes in maths and language arts.

The lasting effects of gender stereotypes on labour market outcomes: Employment and earnings

My research evaluates the impact on long-term outcomes of 1.6 million students from high school to the formal labour market by combining comprehensive administrative records on students’ education with their employment records. The identification strategy uses a value-added framework, comparing students within the same cohort-grade-year and school cells across different teachers, each showing varying levels of stereotypical assessment practices. This approach controls for prior test scores, isolating the influence of teacher bias on student outcomes.

The analysis reveals that teacher stereotypes have differing effects on boys and girls as they enter the workforce. Boys taught by teachers with stronger stereotypical grading practices experience significant employment gains within three years of graduation. In contrast, girls show a smaller and eventually negligible negative impact. This finding reflects a widening gender gap in early career outcomes and suggests that stereotyped assessments in school may contribute to persistent gender inequalities in the labour market.

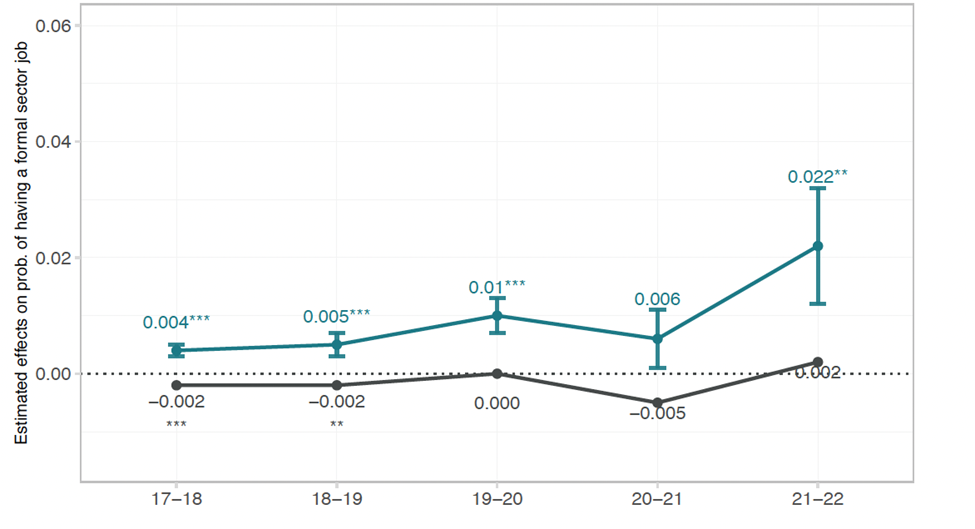

Figure 3: Effects of teachers’ stereotypical assessments on formal sector employment

As shown in Figure 3, the likelihood that a female student works full-time in the formal economy at age 18 to 19 decreases by 0.2 percentage points—about 8% of the mean— for every standard deviation increase in the stereotypical grading bias of her maths teacher. Beyond this age, the total effects on girls’ formal sector employment are no longer statistically detectable. In contrast, boys show consistent positive effects over the course of all five years, amounting to an increase of 0.4—2.2 percentage points in their likelihood of formal sector employment (equivalent to 4% and 12% of the mean).

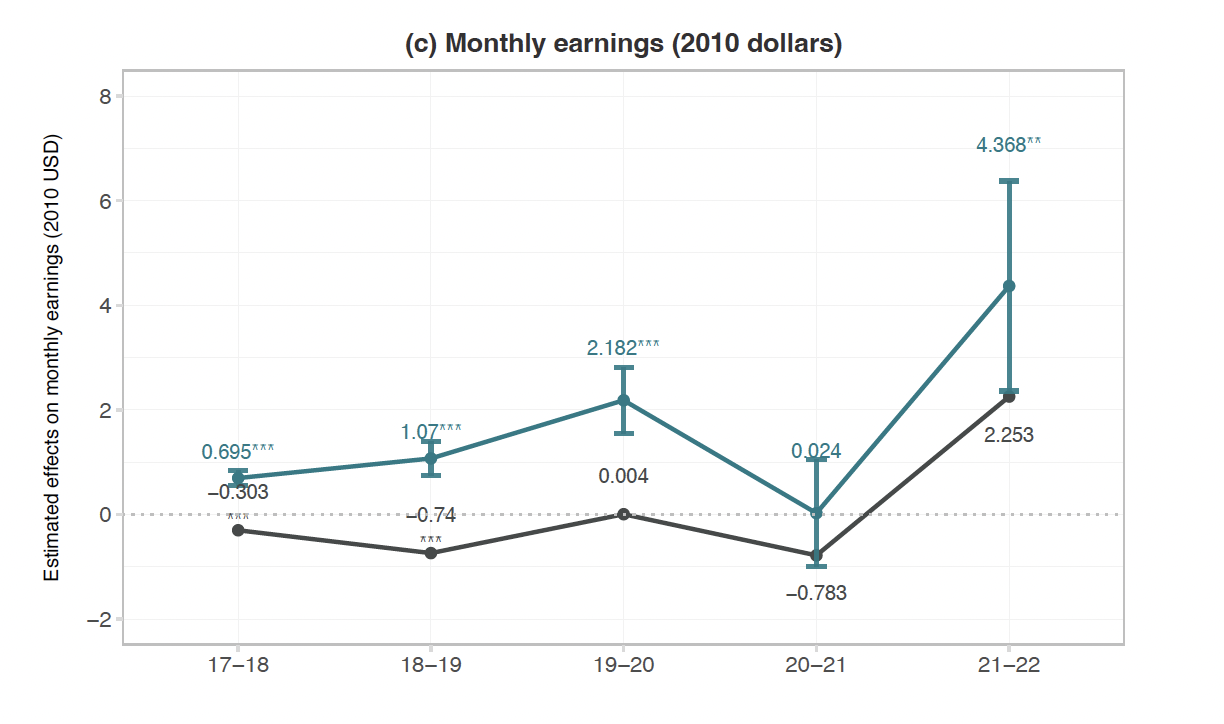

Figure 4: Effects of teachers’ stereotypical assessments on monthly earnings (2010 US$)

The gendered pattern also extends to earnings. For each additional grade level on which girls are exposed to stereotyped assessments, they incur a wage loss between $3.6 and $8.9 annually between ages 17 to 19 (see Figure 4). Consequently, the pay gap between men and women increases by approximately 8% in the first two years following high school graduation.

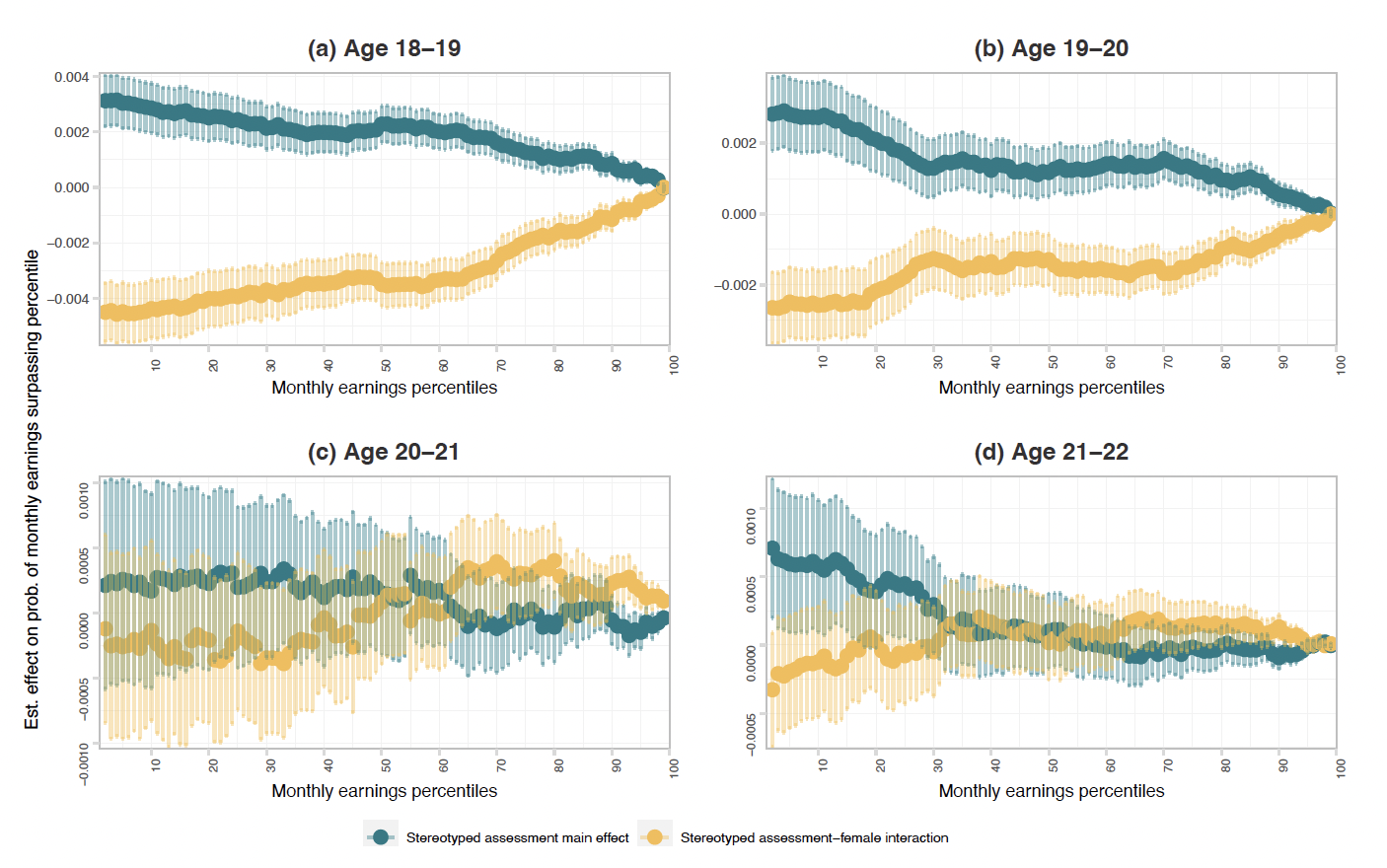

Figure 5: Effects on the probability of students’ earnings exceeding a percentile after high school graduation (ages 18–19)

As seen in Figure 5, these losses disproportionally affect disadvantaged young women that last up to ages 18 to 19, but no discernible pattern is found after that age for them.

Academic careers and high school completion in Peru

Students’ decisions to drop out of high school are influenced by teachers’ stereotypical evaluations reflecting implicitly negative views of girls’ and women’s maths abilities relative to boys’ and men’s.

A one-grade level assignment to a high school maths teacher who exhibits one-standard-deviation more severe gender-stereotyped assessment score against women reduces girls’ likelihood of graduating by 0.5 percentage points (0.6% of the mean) and increases boys’ likelihood of finishing high school by 0.8 percentage points (1% of the mean).

What are the mechanisms that explain how gender stereotypes affect student outcomes?

Firstly, I explore the concept of value added, which can be summarised as the individual contribution of teachers to students’ academic performance. I find that teachers with stronger stereotypes against girls also exhibit lower value-added levels. This aligns with the evidence showing gender-stereotypes differentially decreases girls’ scores by 0.026 standard deviations in eighth grade and 0.01 standard deviations in the twelfth grade. In language arts, similar patterns emerge; stereotyped-assessment language arts teachers decrease girls’ scores differentially by 0.013 and 0.041 standard deviations in eighth and twelfth grade, respectively.

Second, I explore additional mechanisms to explore whether the exposure to teachers’ stereotyped behaviours influences students’ own perceptions of gender-based academic strengths. With this purpose, I use the Implicit Association Test responses from 1,153 students.

The findings indicate that exposure to stereotyped teachers leads female students to internalise the negative gender-based stereotypes of their educators in mathematics classes, as their IAT scores increase. On the other hand, boys whose maths teachers have higher Implicit Association Test scores, indicating stronger stereotypes against girls in maths, show weaker associations of boys having an advantage over girls in maths and related subjects, as measured by a decline in their IAT scores by 0.13 standard deviations. As a result, the evidence suggests that boys internalise fewer stereotypes about their advantage in maths and science when exposed to more stereotyped teachers. This further suggests that the more their teachers hold gendered views, the more boys seem to question or reduce their own stereotypes.

Importance of tackling gender-stereotypes behaviour among teachers

Teachers’ stereotypical assessments are a previously undocumented source of gender gaps in earnings and employment. Given the pervasiveness of teachers’ gender stereotypes and their enduring effects on the gender gap that extends to the labour market, it is imperative for policy interventions to address gender-stereotyped behaviour among teachers.

References

Biasi, B, and H Sarsons (2020), “Flexible wages, bargaining, and the gender gap,” National Bureau of Economic Research w27894, Cambridge, MA.

Carlana, M, “Implicit stereotypes: Evidence from teachers’ gender bias,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 134(3): 1163–1224.

Chetty, R, J N Friedman, and J E Rockoff, “Measuring the impacts of teachers I: Evaluating bias in teacher value-added estimates,” American Economic Review, 104(9): 2593–2632.

Chetty, R, J N Friedman, and J E Rockoff, “Measuring the impacts of teachers II: Teacher value-added and student outcomes in adulthood,” American Economic Review, 104(9): 2633–2679.

Coffman, K B (2014), “Evidence on self-stereotyping and the contribution of ideas,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129(4): 1625–1660.

Exley, C L, and J B Kessler (2022), “The gender gap in self-promotion,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 137(3): 1345–1381.

Le Barbanchon, T, R Rathelot, and A Roulet (2020), “Gender differences in job search: Trading off commute against wage,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 136(1): 381–426.

Niederle, M, and L Vesterlund (2007), “Do women shy away from competition? Do men compete too much?” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(3): 1067–1101.

Martinez, J J (2022), “Long-term effects of stereotypes on labor market gender gaps,” Unpublished manuscript. Retrieved from https://joanjmartinez.nyc3.digitaloceanspaces.com/research/Martinez_2022_LongTermEffects_Gender.pdf.

Rothstein, J, “Measuring the impacts of teachers: Comment,” American Economic Review, 107(6): 1656–1684.

Rothstein, J, “Teacher quality in educational production: Tracking, decay, and student achievement,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 125(1): 175–214.

Rousille, N (2021), “The central role of the ask gap in gender pay inequality.”

World Bank (2022, March 1), “Nearly 2.4 billion women globally don’t have the same economic rights as men.” Retrieved from https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2022/03/01/nearly-2-4-billion-women-globally-don-t-have-same-economic-rights-as-men.

World Bank (2012), World Development Report 2012: Gender Equality and Development.