Fintech has the potential to enhance financial inclusion and welfare for low-income migrants, but its benefits may be limited for migrants with lower financial literacy.

In 2023, migrant remittances to low- and middle-income countries surpassed US$650 billion, impacting one billion people worldwide (World Bank 2024a). Remittances thus serve as a form of social protection, impacting key development outcomes such as health, education, and political participation (Brown 1994, Cox-Edwards and Ureta 2003, Amuedo-Dorantes and Pozo 2011, Koczan and Loyola 2018, López García 2018). Despite their positive welfare impacts, remittances remain relatively costly to send. Globally, sending remittances costs approximately 6% of the amount sent—twice the target set by the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (World Bank 2024b).

Policymakers have argued that financial technologies, or “fintech”, in the form of remittance comparison websites can facilitate consumer search, and, consequently, boost financial inclusion by reducing remittance prices. However, little is known about how low-income migrants with relatively little trust in digital methods interact with fintech. Frequent remittance senders—that is, migrant consumers who send $200-300 monthly—are of particular policy interest, as they incur substantial sending fees (Yang 2011).

Using remittance comparison websites to improve financial inclusion

In a recent paper (Nakasone et al. 2024), we expose Central American remittance senders to a World Bank certified remittance comparison website to assess whether this type of fintech impacts which company they send with (financial inclusion), how they search across companies (measured using eye-tracking), and, indirectly, their welfare.

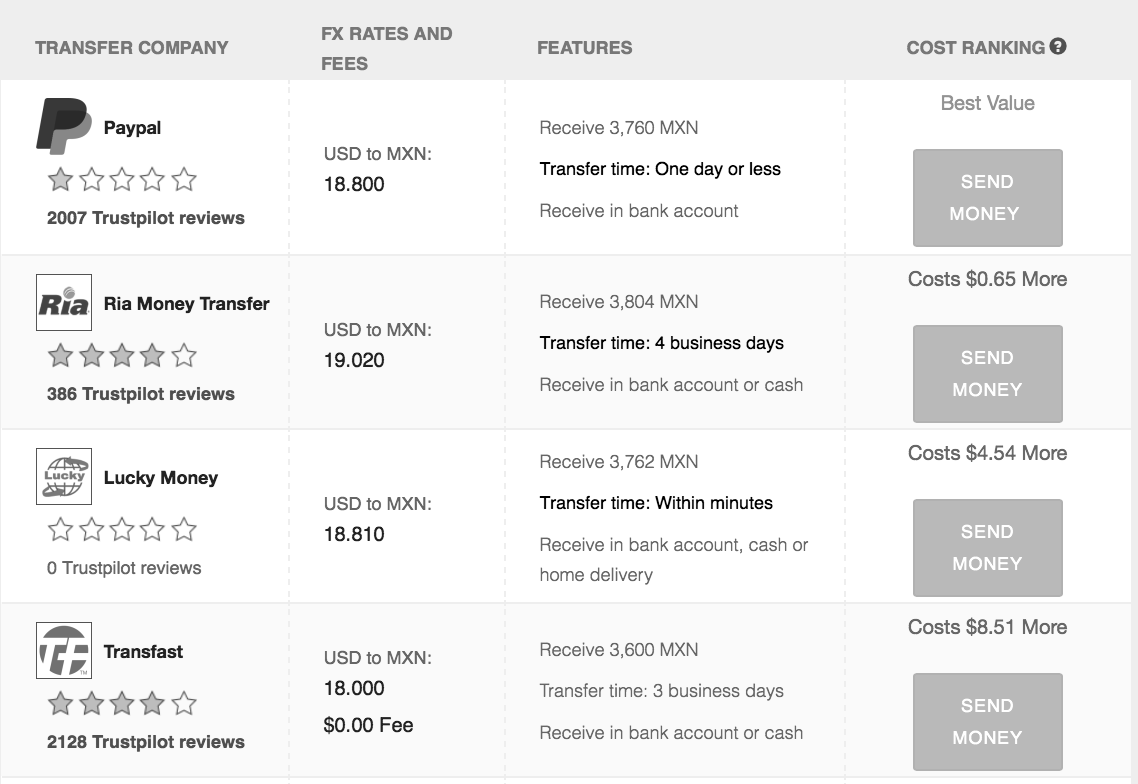

A first-order question is whether migrant consumers respond to information displayed on comparison websites or ignore such information in favour of their usual sending patterns (Figure 1). While 10-28% appear to be loyal to one remittance company, more than 50% “experiment” with different companies once provided with fintech information. This experimentation is rational on average: when migrants learn that a company delivers the money faster (e.g. within minutes versus days), or has a higher rating from prior customers, they are much more likely to send money with that company.

Figure 1: Partial results page for a remittance comparison website

Source: World Bank certified comparison website

While some migrants exhibit remittance habits, others respond rationally to fintech information

That said, some migrants are less likely to respond rationally to fintech information. First, migrants with lower financial literacy and less awareness of comparison websites are less likely to respond to fintech information about prior customer reviews. Second, migrants with lower information-processing capabilities are less responsive to fintech information regarding delivery speed. This suggests that engaging with customer reviews may require a higher level of financial sophistication than evaluating delivery speed. These differences do not exist across other migrant characteristics such as gender, age, or the tendency to compare remittance companies by visiting storefronts or making inquiries.

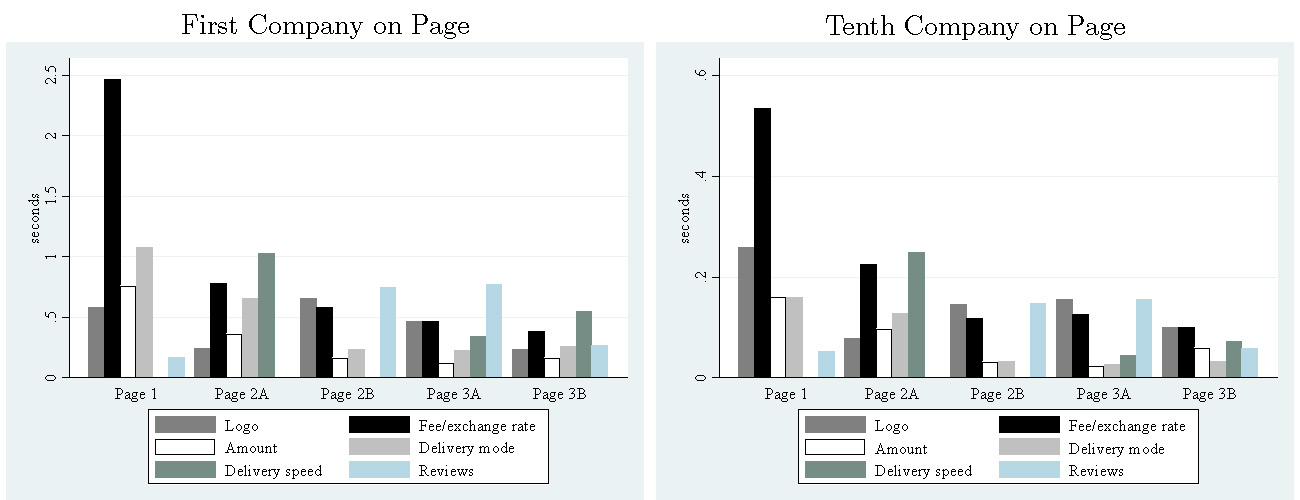

Another question is whether migrant consumers follow certain search patterns when using comparison websites. One way to measure this is by exploiting visual attention data collected using eye-tracking technology (Reutskaja et al. 2011). In this context, four key patterns emerge (Figure 2). First, migrants tend to spend significant time looking at remittance prices (i.e. fees and exchange rates). Second, when provided additional company attributes, such as delivery speed and customer reviews, their visual attention is diverted away from price. Third, migrants search webpages from top to bottom; hence, attributes associated with the first company on the page receive significantly more attention than that of the tenth company. Finally, migrants initially search for their preferred company, that is, the company they have most experience sending with.

Figure 2: Average time spent looking at company attributes depending on company order on the site

Source: Nakasone et al. (2024)

When does fintech improve customer welfare?

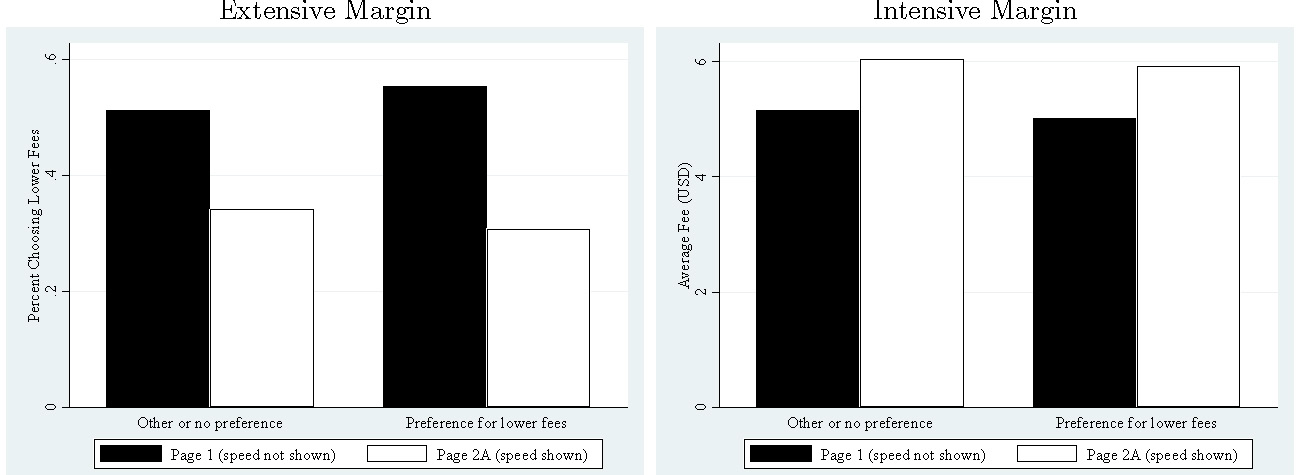

To assess whether comparison websites help migrants make better remittance decisions, their stated preferences for company attributes are compared with their actual behaviour on the website. Specifically, migrants are asked whether they regularly compare remittance companies, and, if so, which attributes influence their decisions (e.g. price, delivery speed, etc.). Most migrants indicate that they usually search for the lowest price. However, when presented with the additional information on the comparison site, 44% of these migrants act inconsistently with their stated preferences. That is, despite stating that they typically prioritise the lowest price, they do not select the lowest-price company when provided information on delivery times. As a result, these migrants end up paying 20-30% more than they would have had they chosen the lowest-price provider (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Migrants behave counter to their lowest-price preferences

Source: Nakasone et al. (2024)

There are two ways to interpret these findings: either these migrants are mistakenly failing to adhere to their stated preferences, or, they are updating their preferences using the additional information provided on comparison websites. Although it is difficult to detangle these behaviours, this inconsistent behaviour is primarily driven by migrant consumers with lower financial literacy, less awareness of comparison websites, and/or lower information processing capabilities. Remittance senders only exhibit this behaviour when the additional information pertains to delivery speed, but not customer satisfaction. While fintech has the potential to improve financial inclusion, consumer search, and welfare, it is not a one-size-fits-all solution.

References

Amuedo-Dorantes, C, and S Pozo (2011), “Remittances and income smoothing,” American Economic Review, 101(3): 582–587.

Brown, R P C (1994), “Migrants’ remittances, savings, and investment in the South Pacific,” International Labour Review, 133(3): 347–367.

Cox-Edwards, A, and M Ureta (2003), “International migration, remittances, and schooling: Evidence from El Salvador,” Journal of Development Economics, 72(2): 429–461.

Koczan, Z, and F Loyola (2018), “How do migration and remittances affect inequality? A case study of Mexico,” VoxDev, 23 November.

López García, A I (2018), “Economic remittances, temporary migration and voter turnout in Mexico,” Migration Studies, 6(1): 20–52.

Reutskaja, E, R Nagel, C F Camerer, and A Rangel (2011), “Search dynamics in consumer choice under time pressure: An eye-tracking study,” American Economic Review, 101(2): 900–926.

World Bank (2024a), “Remittances,” World Bank Brief, 18 September.

World Bank (2024b), “Remittance prices worldwide quarterly,” World Bank, June.

Yang, D (2011), “Migrant remittances,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 25(3): 129–152.