Managers in Indian garment factories use informal worker exchanges to mitigate absenteeism. Expanding these collaborations could unlock significant productivity gains.

The problem of absenteeism in low-income countries

Absenteeism, especially in low-income countries, is a significant issue affecting sectors like education, healthcare, government, and manufacturing, to name a few. Existing studies have measured absenteeism in the public sector, finding in Pakistan, for example, that 68.5% of doctors are absent during working hours (Callen et al. 2017). A large study worldwide (Chaudhury et al. 2006) found that up to 19% of teachers and 35% of health workers were absent from their workplace during unannounced visits.

Quantifying absenteeism, however, is only part of the story. There have been multiple efforts to provide actionable and low-cost interventions to reduce absenteeism that have shown promise. For example, Conditional Cash Transfers in Mozambique seeking to improve school attendance among pupils (De Walque and Valente 2018) or using monitoring innovations like changes in teachers’ contracts or proving attendance with selfies and thumbprints at the beginning of doctors’ workdays in India (Dhaliwal and Hanna 2017, Duflo et al. 2012).

Absenteeism in Indian factories

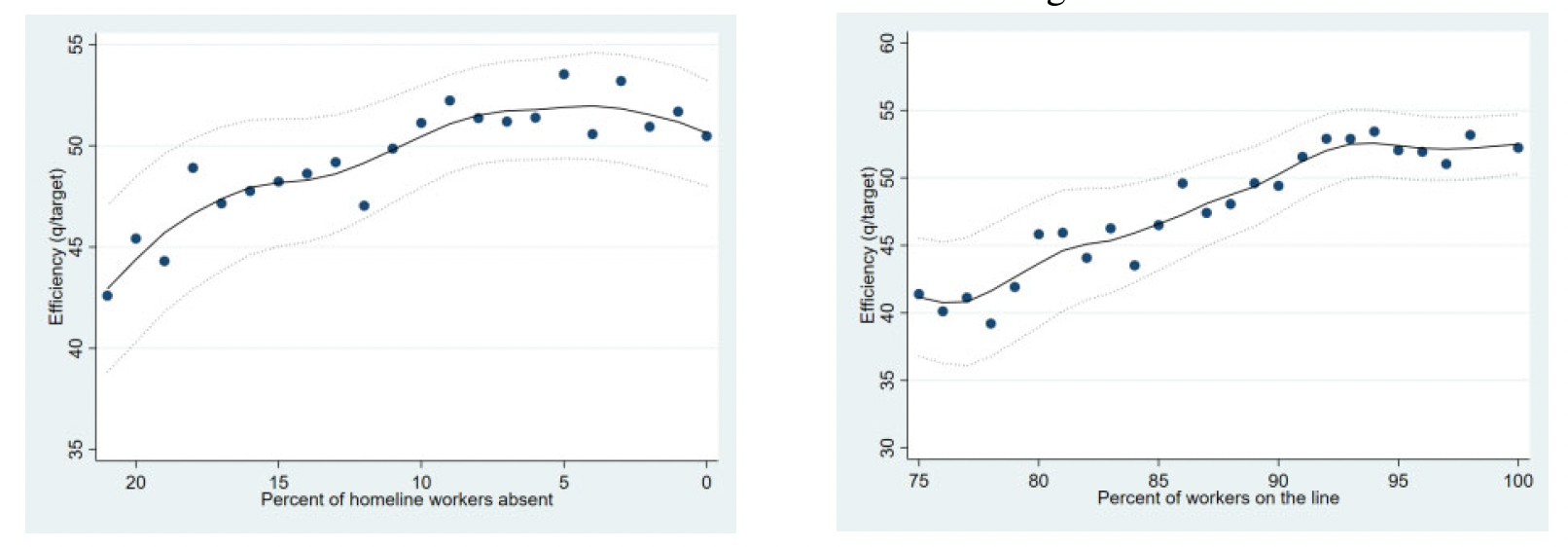

Our research adds to this solution-centred literature by uncovering a common practice of dealing with absenteeism through real-time worker reallocation in the context of a labour-intensive industry. We use data from a large garment manufacturing firm in India, where an average of 11% of workers are absent on any given day, with that figure sometimes reaching 20%. This unpredictability in labour availability creates significant challenges for managers responsible for meeting production targets. Absenteeism affects productivity because fewer workers mean slower production lines, especially when it happens in key operations. We found that managers respond to absenteeism shocks in their production line by borrowing workers from other lines when they face labour shortages. Managers can deal with small absenteeism fluctuations without severe productivity losses, however larger shocks cause notable declines in efficiency (Figure 1). While absenteeism is a problem that affects the whole factory, it affects different production lines to varying degrees on different days (Adhvaryu et al. 2024).

Figure 1: Average line-level efficiency.

A) Average line-level efficiency per percentage B) Average line-level efficiency per percentage of workers assigned to the line workers working on the line

To study these dynamics, we use data from one of the largest ready-made garment manufacturers in the world. We tracked daily absenteeism, worker transfers between teams and line productivity across 73 production lines over several months, allowing us to see how managers deal with worker absenteeism.

Relational contracts as a solution to absenteeism

To cope with absenteeism, managers resort to “relational contracts” - informal agreements that rule the behaviours of individuals within firms (Baker et al. 1994). Like in many other contexts, there are often informal quid pro quos between factory managers, sustained by the value of future relationships. When a production line manager faces high absenteeism, they may borrow workers from another manager's team who is experiencing fewer absences. This borrowing is based on trust and the understanding that the favour will be returned in the future. These exchanges are not formalised but are crucial to maintaining operations.

However, managers don’t form relationships with as many colleagues as they could. Most managers in the factories we studied only borrow and lend workers with two or three partners, even though they could potentially form connections with up to 20 other managers in the same factory. This means that many potentially beneficial exchanges don’t happen, revealing potential line productivity improvements.

Findings of our study across 73 production lines in Indian factories

1. Absenteeism hurts productivity: Productivity is essential in this industry characterised by fierce worldwide competition and low profit margins. We found that absenteeism has a detrimental effect on production lines’ productivity. When absenteeism is below 10%, managers can usually manage with minimal disruptions, but larger shocks can cause substantial productivity losses. On average, a 10-percentage point increase in absenteeism leads to a four-percentage point drop in line productivity.

2. Managers borrow workers, but not enough: Managers do borrow workers to make up for absenteeism, but they don’t always borrow enough to fully offset the losses. As absenteeism increases, borrowing also increases, but it levels off after a certain point. This is likely because managers don’t have enough strong relationships with other teams to borrow a large number of workers when they need them. Despite having the opportunity to form relationships with many other managers, most limit their borrowing and lending to just a few partners. We found that about 72% of all worker transfers occur between the three most frequent partners of a given manager. This suggests that many potential relationships are not being utilised and as a result productivity-enhancing trades are not happening.

Why don’t managers form more relationships?

Many potentially beneficial transfers do not occur because the costs of forming and maintaining relationships with a wider group of managers are too high. Physical proximity and personal characteristics, such as similar education levels or gender influence which managers collaborate. Managers are more likely to form relationships with colleagues who work close to them and who are demographically similar in terms of gender, education, or language. These barriers limit the number of managers each individual collaborates with, even though expanding these networks could lead to significant productivity gains.

Another reason why managers don’t lend more workers is that doing so comes with risks. Managers receive bonuses based on their team’s productivity, so lending workers to another team could reduce their chances of hitting performance targets. However, the fact that managers continue to lend workers despite these risks suggests that the long-term benefits of maintaining good relationships with other managers outweigh the short-term costs.

What if managers formed more relationships?

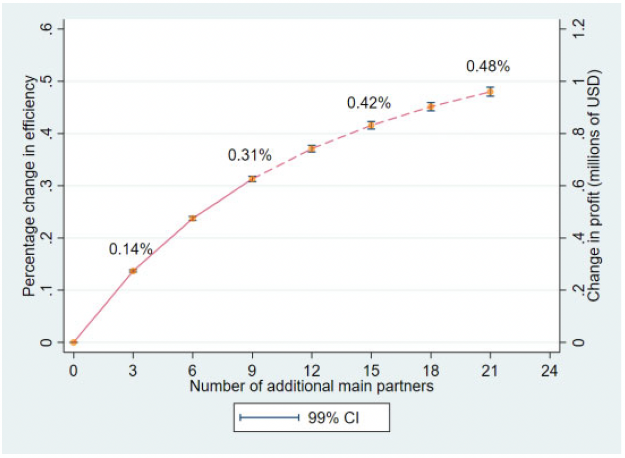

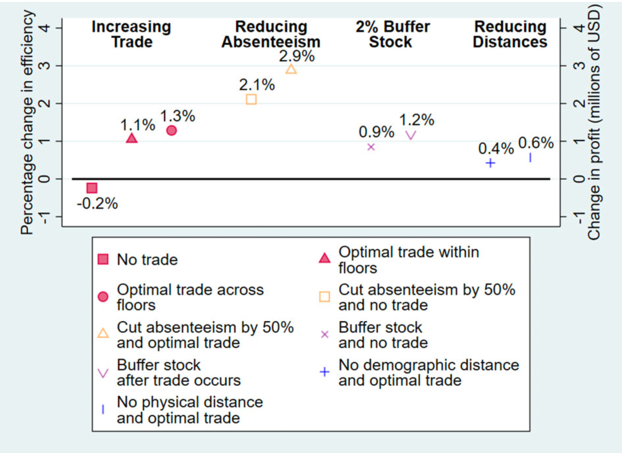

We conducted simulations to explore what would happen if managers formed more relationships and borrowed and lent workers more frequently. Our results show that if managers could reduce the costs of forming new relationships (for example, by using better communication tools or support from higher-level management), factory productivity could increase by up to 0.5%. For the firm in our study, this would translate into an additional one million USD in annual profits, reaching approximately half of the gains that could be achieved in a theoretical first-best scenario where all present workers could be traded efficiently without any friction.

Figure 2: Panel A) Plant-level gains in efficiency with main partners, B) Plant-level gains in efficiency across simulations

Notes: Panel a): Efficiency is first measured without added main partners, then recalculated with 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, and 21 additional partners, showing the percentage increase. Panel b): Starting from a baseline efficiency level, gains are calculated under various conditions: (1) absenteeism remains constant with no manager trades, (2) optimal worker trading within floors, (3) optimal trading across floors, (4) absenteeism cut in half without manager trades, and (5) optimal trading with reduced absenteeism. Additional scenarios introduce a 2% worker buffer within floors, both (6) without and (7) with line-to-line trades. Lastly, efficiency is calculated with (8) demographic differences removed and (9) physical distance reduced to 1 foot.

Notes: Panel a): Efficiency is first measured without added main partners, then recalculated with 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, and 21 additional partners, showing the percentage increase. Panel b): Starting from a baseline efficiency level, gains are calculated under various conditions: (1) absenteeism remains constant with no manager trades, (2) optimal worker trading within floors, (3) optimal trading across floors, (4) absenteeism cut in half without manager trades, and (5) optimal trading with reduced absenteeism. Additional scenarios introduce a 2% worker buffer within floors, both (6) without and (7) with line-to-line trades. Lastly, efficiency is calculated with (8) demographic differences removed and (9) physical distance reduced to 1 foot.

Policy implications for management practices and policy to reduce absenteeism

Our findings have important implications for both management practices and policy. By reducing barriers to collaboration between managers, firms can significantly improve productivity:

1. Facilitate communication: Implementing systems that make it easier for managers to identify opportunities for borrowing workers across teams could reduce the costs associated with forming relationships. For instance, introducing communication tools that help managers share information about absenteeism in real time could foster more effective collaboration.

2. Incentivise cooperation: Firms could incentivise cooperation between managers by restructuring bonuses or creating formal mechanisms that reward managers for lending workers to others. This could address the current disincentive where managers are reluctant to lend workers due to the risk of missing productivity targets.

3. Managerial training: Training programmes that focus on building collaborative skills among managers and encouraging a culture of teamwork could also help reduce the barriers to forming new relationships.

Relational contracts play a crucial role in mitigating the negative impacts of absenteeism in the workplace, particularly in labour-intensive industries like garment manufacturing. While managers use creative informal solutions to cope with absenteeism shocks, there is significant untapped potential for productivity gains if firms can reduce the barriers to broader cooperation. By reducing the barriers to collaboration, firms could significantly boost productivity, translating into real financial gains and better outcomes for both workers and management.

References

Adhvaryu, A, J F Gauthier, A Nyshadham, and J Tamayo (2024), “Absenteeism, productivity, and relational contracts inside the firm,” Journal of the European Economic Association, jvae026.

Baker, G, R Gibbons, and K J Murphy (1994), “Subjective performance measures in optimal incentive contracts,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 109: 1125–1156.

Callen, M, S Gulzar, A Hasanain, M Y Khan, and A Rezaee (2020), “Data and policy decisions: Experimental evidence from Pakistan,” Journal of Development Economics, 146: 102523.

Chaudhury, N, J Hammer, M Kremer, K Muralidharan, and F H Rogers (2006), “Missing in action: Teacher and health worker absence in developing countries,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(1).

De Walque, D, and C Valente (2018), “Incentivizing school attendance in the presence of parent-child information frictions,” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, (8476).

Dhaliwal, I, and R Hanna (2017), “The devil is in the details: The successes and limitations of bureaucratic reform in India,” Journal of Development Economics, 124: 1-21.

Duflo, E, R Hanna, and S P Ryan (2012), “Incentives work: Getting teachers to come to school,” American Economic Review, 102(4): 1241–1278.