The creation of smaller local government polities resulted in greater public good access across multiple dimensions – village-level infrastructure, individually-targeted benefit programmes, and workfare programmes – over both the short and long run.

Decentralisation and the devolution of power to local governments have commonly been used by developing countries as a means of improving service delivery. The size of these political units may be an important input in the effectiveness of these policies, but empirical evidence on the consequences of polity size has been difficult to come by. Various political economy models suggest that smaller local governments may offer several advantages, such as better catering to diverse preferences and encouraging public good provision through interjurisdictional competition (Tiebout 1956, Besley and Case 1995, Oates 1972). Alternatively, small governments also have many potential costs. Smaller political units may be susceptible to elite capture, miss out on economies of scale, and have lower levels of political competition (Bardhan and Mookherjee 2000, Bardhan 2002).

Our research (Narasimhan and Weaver 2023) uses a large-scale reform in the most populous state of India, Uttar Pradesh, to causally identify the effects of smaller polity size on a variety of socioeconomic outcomes. The reform focused on village councils, also known as gram panchayats, the lowest level of elected government in India. They are responsible for local public goods provision and are a key player in various welfare and workfare programmes.

Gram Panchayats in Uttar Pradesh

A large-scale federal reform in 1992 in India devolved power to local village councils throughout the country. These gram panchayats (GPs) have local representatives from each of the villages within the body along with a single head, known as the pradhan. All positions are filled through democratic elections every 5 years. The gram panchayat is responsible for overseeing the provision of local public goods, such as education, roads, and sanitation. They also play a major role in the implementation of various central and state government welfare programmes, where the most important is a workfare programme (National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme, NREGS). In addition to these formal duties, the leaders of the gram panchayat are instrumental in advocating with bureaucrats and politicians for resource allocation to their GPs and assisting their constituents in accessing benefit programmes (Bussell 2019).

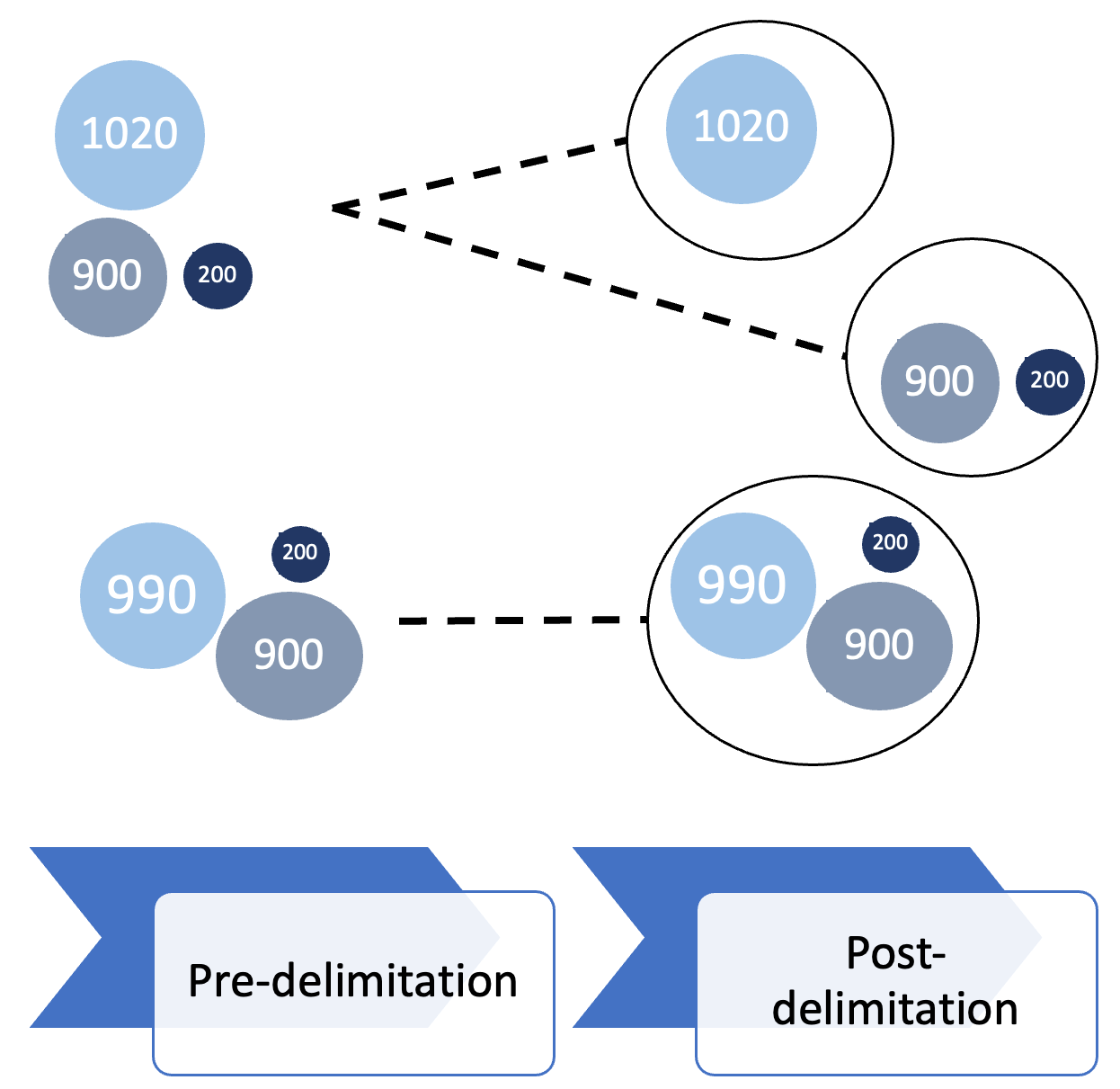

Figure 1: Village delimitation into Gram Panchayats

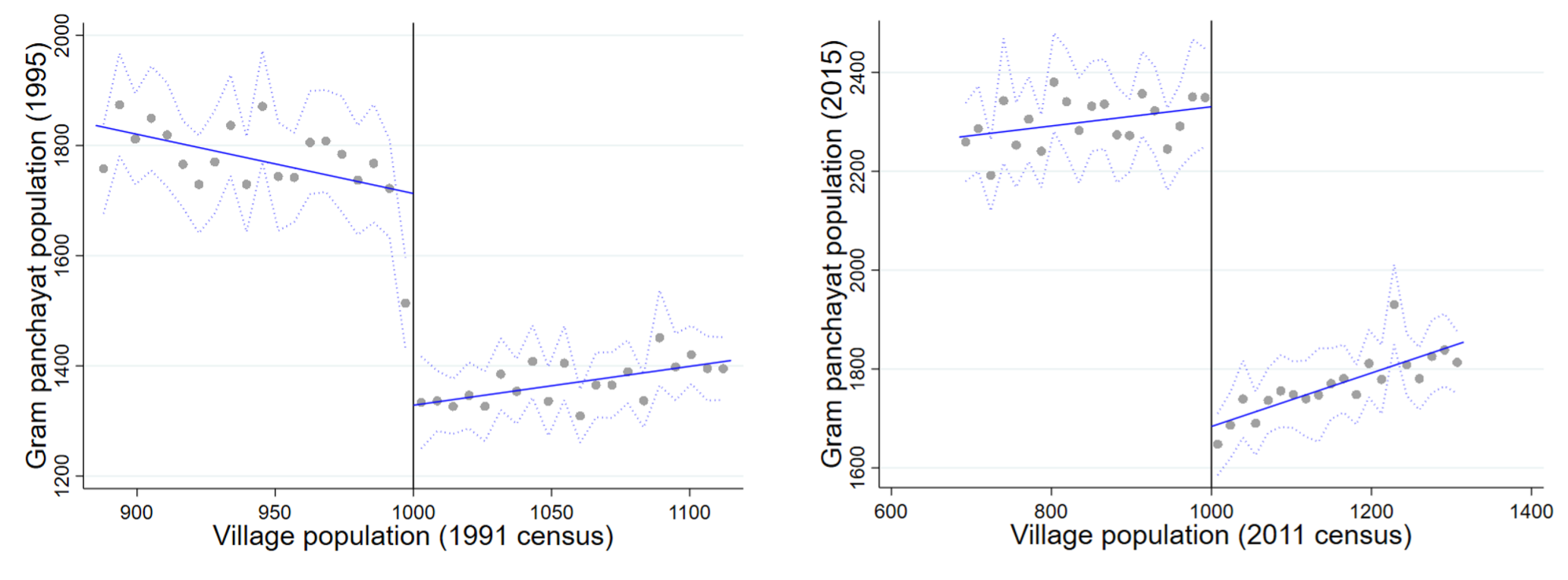

Our study focuses on the state of Uttar Pradesh, which uses a unique rule to allocate villages into GPs. This rule states that villages with populations above 1000 in the most recent decadal census should be allocated into their own GPs rather than be in a GP including other villages; as a result, villages with populations below 1000 are allocated to much more populous GPs than those with populations just above this threshold, as shown in Figure 1. This structure allows us to use a regression discontinuity approach in which we compare villages with populations just below 1000 (allocated into larger polities) with villages with populations just above it (allocated into smaller polities). Aside from the GP that they are assigned to, these villages are otherwise quite similar at the time of delimitation. We focus on the two rounds of delimitation based on this rule. The first is from 1995, based on the 1991 population census, whilst the second happened in 2015, and was based on the 2011 population census. As seen in Figure 2, villages with populations just below 1000 are allocated into significantly larger GPs. In the paper, we conduct a variety of checks to show that our results are driven by this polity size policy rather than other federal or state programmes.

Figure 2: Village population and polity size

Key results

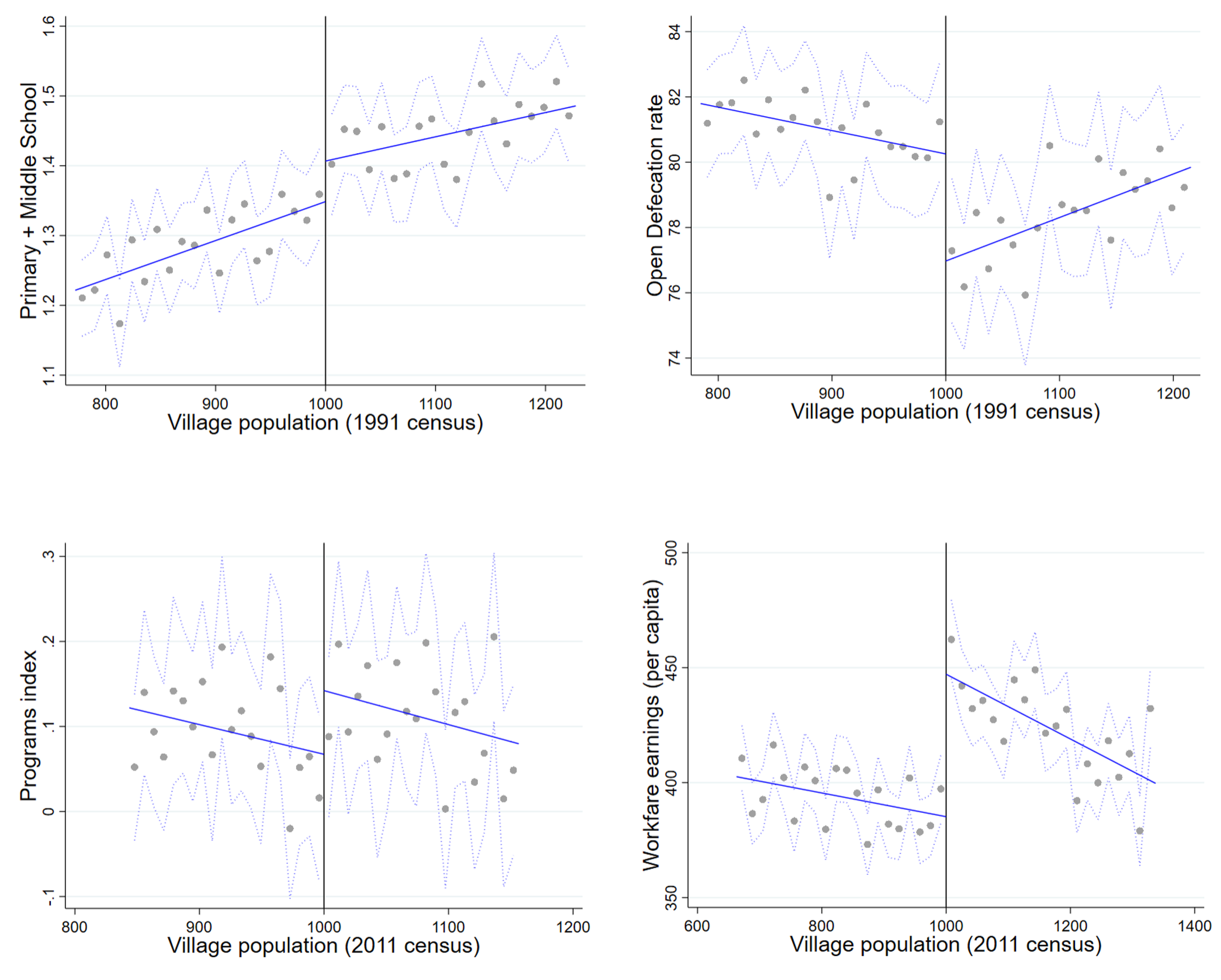

This paper combines thirty years of census and administrative data to generate a dataset with detailed information on key public service delivery outcomes. In terms of village-level outcomes, we find that villages assigned to smaller local governments experience substantial improvements in infrastructure and public benefit access. These villages have better availability of educational facilities (both at the primary and middle school level), which results in significant gains in educational attainment over time, as well as improved access to all-weather roads and subsidised food access (see Figure 3a for schools; see paper for other outcomes).

At a more individual level, we find that houses in villages under smaller GPs are built from higher quality materials. Additionally, they are 16-18% more likely to have access to toilets and closed drainage systems, which decreases the incidence of open defecation (Figure 3b). These improvements can be attributed to better implementation of important housing and sanitation programmes, for which local leaders play a pivotal role. Furthermore, we find that citizens in smaller GPs have better access to various other benefit programmes (Figure 3c), including pensions and below poverty line ration cards, as well as evidence that these programs are better targeted to poor households. This suggests that across the board, smaller polities are more effective at helping citizens to make claims on the state.

Figure 3: Effects of polity size for selected outcomes

Finally, we examine the effect of smaller polities on access to the NREGS workfare programme. We find that individuals in smaller GPs have better access to the programme, where NREGS earnings are significantly higher (16%; Figure 3d). These effects are also consistent when we break down the analysis by caste and gender, showing similar gains across the board.

Why did changing administrative unit size improve local government performance?

Our empirical setting also allows us to examine the mechanisms responsible for the observed effects. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for determining the broader applicability of the findings and for shedding light on numerous theoretical concepts in the decentralisation literature.

First, we use detailed data on GP budgets in order to rule out mechanical fiscal channels favouring smaller polities. However, we do observe strong evidence for political mechanisms. Using data from local elections, we find that in smaller polities, there is heightened civic engagement (Das 2015), and elected representatives and candidates are less likely to have criminal records (Banerjee et al. 2014, George et al. 2019, Boffa et al. 2016). Contrary to concerns of elite capture (Bardhan and Mookherjee 2000, 2006), where powerful individuals dominate leadership positions, the study finds no increase in the election of high caste or wealthy individuals, and service access improvements are similar across caste groups. Additionally, the effects of decentralisation appear more pronounced in villages that, before boundary redefinition, were not the largest in their GP, and so redrawing boundaries enhances their political influence.

Concluding remarks

Taken together, our findings suggest that smaller polities provide a variety of additional benefits to their citizens, with evidence that this stems from political mechanisms. In the paper, we further investigate the effects of transitioning citizens between specific polity sizes, for instance, what is the effect of moving from a polity size of 6000 to one of 1000, compared to a shift from 3000 to 1000. These results can aid in the creation of effective local government units, as well as highlighting some of the key channels through which the policy can be most effective.

References

Banerjee, A, D P Green, J McManus, and R Pande (2014), “Are poor voters indifferent to whether elected leaders are criminal or corrupt? A vignette experiment in rural India.” Political Communication 31 (3): 391–407.

Bardhan, P (2002), “Decentralization of governance and development.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 16 (4): 185–205.

Bardhan, P and D Mookherjee (2000), “Capture and governance at local and national levels.” American Economic Review 90 (2): 135–139.

Bardhan, P and D Mookherjee (2006), “Decentralisation and accountability in infrastructure delivery in developing countries.” The Economic Journal 116 (508): 101–127.

Besley, T and A Case (1995), “Incumbent behavior: Vote-seeking, tax-setting, and yardstick competition.” American Economic Review 85 (1): 25.

Boffa, F, A Piolatto, and G AM Ponzetto (2016), “Political centralization and government accountability.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 131(1): 381–422.

Bussell, J (2019), “Clients and constituents: Political responsiveness in patronage democracies.” Modern South Asia.

Das, S (2015), “Efficacy of Town Hall Meetings in Electoral Democracy: Theory and Evidence from Indian Village Councils.” Working Paper.

George, S, S Gupta, and Y Neggers (2019), “Can We Text Criminal Politicians Out of Office? Evidence from a Mobile Experiment in India” Technical Report, Working paper.

Narasimhan, V., & J Weaver (2023), “Polity size and local government performance: evidence from India.” Available at SSRN 4678837.

Oates, W (1972), Fiscal Federalism, New York: Harcourt.

Tiebout, C M (1956), “A pure theory of local expenditures,” Journal of Political Economy 64 (5): 416–424.