Decentralising the monitoring of public sector workers is cost-effective, but as central state capacity increases this advantage disappears

High absence rates have been found among public sector workers across the developing world in workplaces such as schools and medical facilities (Chaudhury et al. 2006). Monitoring absence and effort on the job is even more difficult for workers such as agricultural extension agents, whose job requires them to visit farmers who live out in rural areas, often far from agricultural ministry offices.

Especially in settings where central governments know little about lower-level employees, previous theoretical research has suggested that giving autonomy and authority to middle managers will be effective (Mookherjee 2006). These presumptively better informed managers would know which employees will benefit most from monitoring. Partly for this reason, government decentralisation has been a major trend in government reform over the last few decades. However, it is unclear whether the rapid development of cheap and easily dispersed information and communication technologies will erode the information advantage of middle managers and reverse the cost-benefit analysis when considering decentralisation.

Our study: New civil servant monitoring technology in Paraguay

In Dal Bó et al. (2018), we present the results of a randomised controlled trial conducted in Paraguay examining the impact of a new monitoring technology on the performance of state employees, specifically agricultural extension agents. In addition, we compare the efficiency of a decentralised allocation of this technology with that of different algorithms that a central government might use to allocate the technology.

We analysed:

- the effects of cell phone monitoring on agent performance;

- whether supervisors are able to identify those agents who would most benefit from being monitored; and

- how the central government could replicate, and even improve upon, the allocation rules used by supervisors.

Context: Agriculture extension services in Paraguay

Extension agents resemble the role of middlemen, connecting farmers with cooperatives, private enterprises, and specialists. They work out of 182 district-level offices which fall under the central Ministry of Agriculture. Although the headquarters for extension agents are in towns, most of their daily work involves driving out to visit farmers in the rural areas where they live and work. Within every district office there is a supervisor who, in addition to working with his own farmers, must also monitor the other extension agents working in the district.

In June 2014, Paraguay’s Ministry of Planning provided extension agents with GPS-enabled cell phones. One objective was to improve coordination and communication between the agents and their supervisors. Also, the phones would allow the organisation to geographically track agents. As there were not enough resources to provide all extension agents with these GPS-enabled cell phones, we worked with the government to both measure the impact of the phones and determine how to distribute them to yield the greatest impact.

Before phones were issued, we asked each district supervisor to indicate which half of his agents should receive the phones, given the programme’s objective to increase agent performance. We refer to these supervisor-identified agents as the ‘selected’ agents. In some randomly chosen districts, phones were distributed to all agents while in other districts the phones were not distributed to any agents. This simple design allows us to measure both the average impact of the monitoring technology as well as the differential impact on those whom the supervisors considered most worthy of being treated.

Results

1. Monitoring improves performance

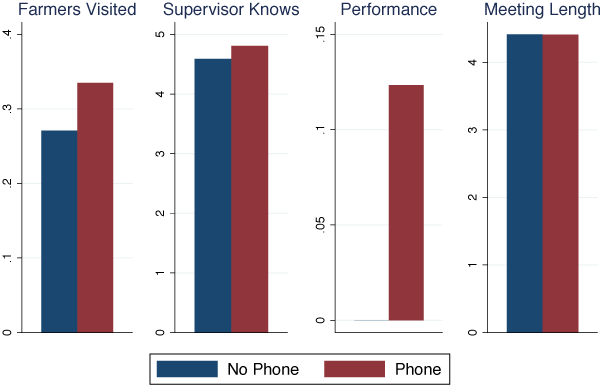

Figure 1 shows how the cell phones had a sizeable effect on extension agent performance with results suggesting a six percentage point increase in the share of farmers visited in the last week. This represents a 22% increase over the agents in the control group. In addition, a normalised performance metric based on farmer satisfaction with the support they get from the agent is higher for farmers working with monitored agents. The reason for increased performance is likely a perception by agents of tighter control: monitored agents were more likely to agree with the statement that their supervisor knows their whereabouts. We find no evidence that treated agents increased the number of visits at the cost of conducting shorter ones.

Figure 1

Notes: The first figure shows share of farmers visited. The second figure shows the likelihood that the supervisor knows where the agent is. The third figure shows normalised agent performance measure. The fourth figure shows the log of length of the most recent farmer-agent meeting.

2. Supervisors have valuable performance information

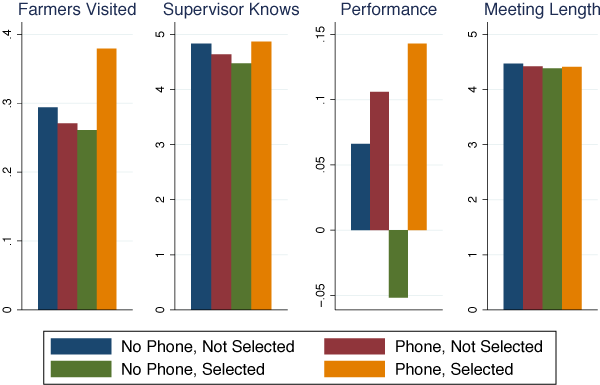

Not all treated agents reacted equally to being issued a phone, as shown in Figure 2. The supervisor-chosen agents respond more to increased monitoring and in fact drive the entire effect of the intervention. The impact of the phones on those selected by the supervisors is shown in the comparison between the green and yellow bars. Results suggest that treatment increased the likelihood that a farmer of a selected agent was visited in the past week by 15 percentage points compared to a statistically insignificant 4 percentage point decrease among those who were not selected. The implication is that supervisors do have superior knowledge about how to assign treatment.

We find that the supervisors’ advantage is not explained by their knowledge of easily observed demographic traits (age, gender, etc.), nor by harder-to-measure characteristics such as the agents’ intellectual ability or personality type. While our findings suggest that supervisors have valuable information about the agents they work with, the decision of whether or not to decentralise depends on the information held by the central government, the feasible allocation rules it could adopt, and the extent of available resources.

Figure 2

Notes: The first figure shows share of farmers visited. The second figure shows the likelihood that the supervisor knows where the agent is. The third figure shows the normalised agent performance measure. The fourth figure shows the log of length of the most recent farmer−agent meeting.

3. Decentralisation is valuable, but may lose appeal as central authorities build data capabilities

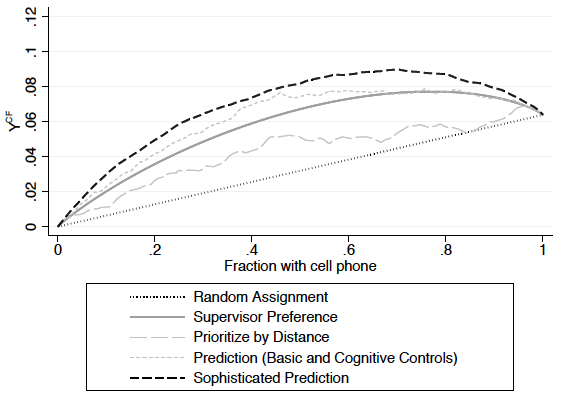

Needless to say, if every intervention were rolled out to nobody or, at the other extreme, universally, there would be no value in trying to figure out, centrally or through supervisors, who should be treated first. It follows that roll-out scale is crucial to measuring the value of decentralisation. But what the central authority can realistically learn is also crucial. We constructed four counterfactuals corresponding to different degrees of sophistication of the central authority. Our first counterfactual is random assignment. This corresponds to the dotted diagonal line in the figure. If the central government decided to allocate the phones to everyone, then the expected effect would be a 6 percentage point increase in the likelihood that a farmer of a selected agent was visited in the past week. If instead they only had resources to treat a randomly chosen half of the agents, then we would expect a 3 percentage point increase. A random selection rule gives a treatment impact that traces a straight line from zero to the average treatment effect as a function of roll-out scale.

We find that the value of supervisor information is substantial relative to a regime in which the principal allocates phones at random. The supervisor selection allocation rule is represented by the solid curve. The difference in programme impact is maximised at 53% coverage at which point the supervisor allocation increases the share of farmers visited by 7 percentage points versus only a 3 percentage point increase under random assignment.

Figure 3

Notes: The y-axis shows the total treatment effect at different scales of roll-out under different assignment rules. Under random assignment the treatment assignment is made randomly; with supervisor preference the treatment assignment is what would be achieved under decentralization if supervisors made the assignment decision based on all the information they had; prioritize by distance is what would happen if treatment were assigned first to those AEAs whose beneficiaries live further from the local ALAT office; prediction (basic and cognitive controls) uses the control group to predict baseline performance using the observable variables and then treats first those AEAs who are predicted to be the worst performers in the baseline; sophisticated prediction runs a pilot experiment at low roll-out to establish a map between treatment response and observables and then treats first those AEAs who are predicted to have the highest treatment response.

A second, and slightly more effective, approach for the central government would be to allocate phones to the agents who have to travel the longest distances to reach their farmers. This method is shown by the broken lined curve and generally outperforms random assignment (a 2 percentage pointadvantage at 50% coverage), but the supervisor still outperforms this simple assignment mechanism.

A third centralised policy assumes the central government would observe pre-existing performance by agents and then roll out phones starting with the lowest performing agents. A government with the information and capacity to approximate this procedure can perform at least as well as, and in many cases better than, the supervisors as shown by the top lighter broken curve in the figure.

Finally, the most information-demanding centralised policy we consider uses agent observables to predict response to treatment. This would require the central government to conduct a pilot experiment to investigate the link between agent observables and response to treatment and use that to determine treatment.Treating agents in descending order of responsiveness vastly outperforms decentralised assignment by the supervisors as seen in the top darkest broken curve.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that progress in information and communication technologies may alter the optimal decentralisation decisions in government. A central government with better ability to generate and analyse data may find it desirable to re-centralise functions that had been previously decentralised. While our specific quantitative findings may not be generalisable, our method of comparing centralised versus decentralised arrangements is, and it can be easily exported to other settings.

References

Chaudhury, N, J Hammer, M Kremer, K Muralidharan and F H. Rogers (2006),“Missing in action: Teacher and health worker absence in developing countries”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 20(1): 91-116.

Dal Bó, E, F Finan, N Li and L Schechter (2018), “Government decentralisation under changing state capacity: Experimental evidence from Paraguay”, NBER Working Paper 24879.

Mookherjee, D (2006), “Decentralisation, hierarchies, and incentives: A mechanism design perspective”, Journal of Economic Literature 44(2): 367–390.