There are significant disparities across countries in the gender division of work even at similar income levels. Social, institutional, and policy choices play a pivotal role in the variation in gendered labour patterns across countries.

Despite progress in reducing gender gaps in educational attainment and wages, the gender division of work remains strikingly uneven across countries. In many high-income nations, women now make up a substantial part of the workforce, yet they still shoulder the majority of unpaid domestic and care work. Meanwhile, women's market work remains limited – especially in a set of middle- and low-income countries. Our research examines these disparities, revealing that a set of frictions, policies, and social choices – which we summarise as “gender wedges”—play a critical role in shaping the global variation in how men and women divide their time between market and non-market work.

In a new study (Gottlieb et al. 2024), we document the gender division of work across 50 countries and its evolution over time in five countries. We measure not only time spent in market work (which includes wage employment, self-employment, and activities like subsistence agriculture) but also domestic and care work. We also provide evidence on the factors that determine how men and women divide their time between market and non-market work across countries, in particular, the role of wage gaps versus various non-wage factors.

Countries vary enormously in the gender division of work

To consistently measure and compare the time use of men and women across countries, we harmonised data from Time Use and Labor Force Surveys from 50 countries. These time-use surveys record in detail how each respondent allocated time over a complete 24-hour day. Figure 1 plots country averages against GDP per capita (PPP). Figure 1a shows average market, domestic, and care hours worked by married men, while Figure 1b shows the same statistics for married women.

Figure 1a: Weekly hours worked by married men

Figure 1b: Weekly hours worked by married women

Notes: Each dot shows average weekly hours worked for married individuals aged 15-64 for a country survey, plotted against GDP per capita (PPP) from Feenstra et al. (2015) for the corresponding year. Figure 1a features linear lines of best fit and Figure 1b features quadratic lines of best fit.

The figure finds weak support for the existence of a U shape in women’s market work for countries at different levels of income per capita – in line with evidence by Sinha (1965), Boserup (1970), and Goldin (1994) – but also reveals additional large disparities in how men and women allocate their time. In high-income countries, married women work about 60-65% as many hours in the market as married men, but they work 1.5 to 2 times as much within the home, in domestic services and care work. In low-income countries, both gaps are larger, as men work longer market hours but do less domestic work.

Yet what is most striking in Figure 1b is the sheer variation in work choices across countries. This dispersion is particularly pronounced in middle-income economies. Market hours worked by women vary by a multiple of five or more across countries in this group. Married women work only about a quarter as many market hours as men in India and several other countries – but more than five times as many hours in the household. In contrast, married women in China and several other countries work more in the market and less in the household than their counterparts in rich countries.

What explains these large differences in work choices?

Research and policy work have suggested numerous potential determinants of gender differences in work choices. They can be grouped into three categories. Firstly, differences in market wages for men and women with similar observable characteristics (the so-called “gender wage gap”) should imply differences across countries in the gender division of work.

Second, time allocation might differ because of non-wage gender-specific factors, like social norms on the appropriateness of different types of work for men and women; the nature of work; or the possibility of harassment at work or in public spaces. Similarly, non-wage economic factors (e.g. asymmetries in the tax system arising from progressive taxes on joint household income, or gender asymmetries in retirement regimes e.g. Kaygusuz 2010, Guner et al. 2012, Bick et al. 2017) affect women’s and men’s time allocation differently. We refer to these factors jointly as “gender wedges.” They capture gender differences in all non-wage work (dis)incentives, including social norms, institutional barriers, etc. (Burstyn et al. 2020, Heath et al. 2024, Jayachandran 2021).

A third category consists of factors that per se are gender-neutral, such as the absence or high cost of childcare outside the household. These factors are gender neutral, in a sense; but they can exacerbate an unequal gender division of work arising from gender wage gaps or gender wedges (Greenwood et al. 2005).

All three groups of factors have received significant attention in recent research. Our rich set of measures, combined with a model of household time use, allow us to disentangle them and to isolate the role each factor plays in shaping the gender division of market, domestic, and care work.

Gender wedges are large and vary strongly across countries

Our analysis suggests that gender wedges play a dominant role in determining differences in the allocation of work across countries. Collapsing these to a single number, we estimate that they account for approximately 60% of the variation in gendered labour patterns across countries.

Figure 2 shows the estimated gender wedge related to market work for each country on the horizontal axis. A wedge greater than one arises where women’s market work is below levels implied by wages and their non-market work. The Figure shows that wedges are large and vary enormously across countries. The units of wedges have economic meaning: eliminating the mean wedge of 1.28 has a similar effect on women’s market work as reducing the gender wage gap by 40%.

It is also clear from comparing Figures 1 and 2 that countries where women perform particularly little market work, have particularly large gender wedges. This reflects the fact that gender wage gaps, while substantial and varied across countries, are not noticeably larger in the countries where women work least and that households do not as a whole devote more time to home production in these countries, suggest that the large differences in the gender division of work in these places must reflect other non-wage gender-biased factors – what we term gender wedges.

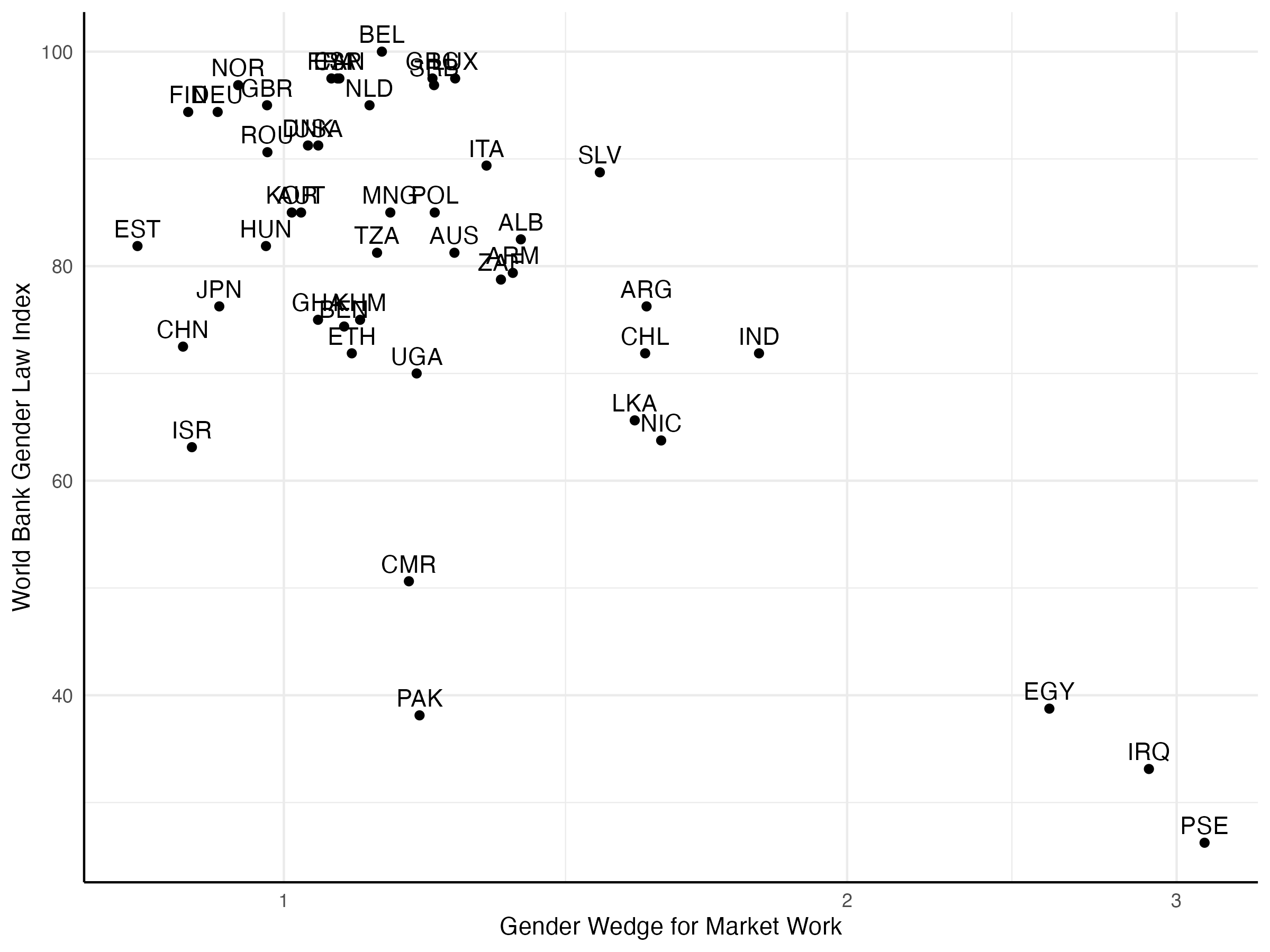

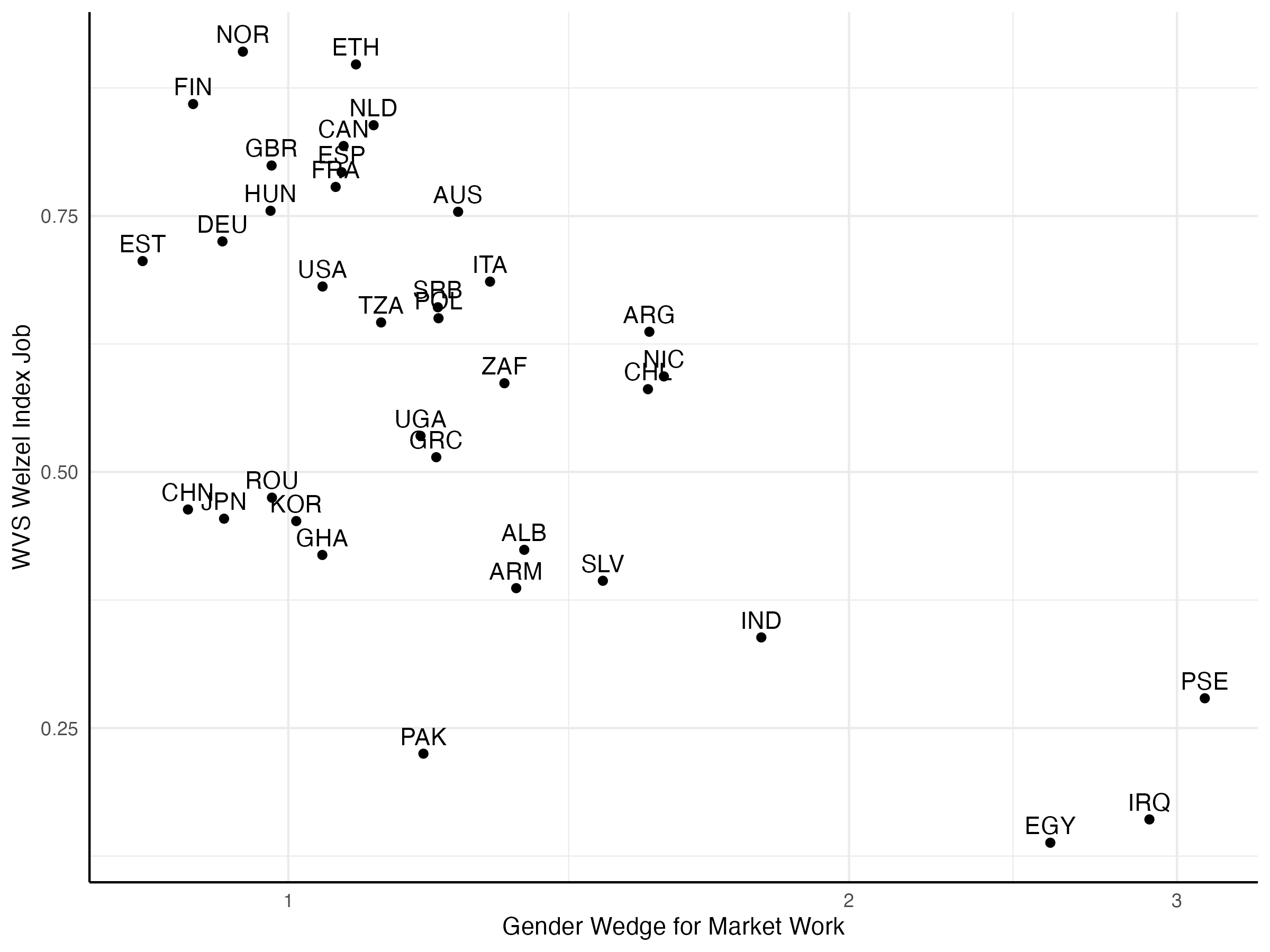

Gender wedges reflect social norms and policies

To shed further light on the determinants of the gender division of work, Figure 2 plots estimated gender wedges against measures of social norms and policies. The left panel plots the World Bank’s Women, Business, and the Law Index (World Bank 2024) against the gender wedge for market work for each country. The right panel plots an index based on the World Values Survey question “When jobs are scarce, men should have more right to a job than women.” against the gender wedge (Inglehart et al. 2020). It is clear that countries with larger gender wedges have systematically lower values of both indices, indicating less gender-equal laws and values.

Figure 2: Gender wedge for market work strongly correlates with (a) World Bank Gender Law Index and (b) the World Value Survey Gender Job Index.

Notes: A gender wedge of 1 indicates gender-neutral non-wage work incentives. The values of the WB index range from 0 and 100, with higher values indicating more gender-equal laws. The WVS Job Index is based on replies to the survey question: “Do you agree, disagree or neither agree nor disagree with the following statements? - When jobs are scarce, men should have more right to a job than women.” Higher WVS values correspond to more gender-equal values.

The gender division of work over time: Two case studies

Our analysis also sheds light on the evolution of the gender division of work over time, in selected countries with available data. As is well known, women's market work increased significantly over the last few decades in the United States. Our analysis suggests that this was driven primarily by wage factors, particularly the reduction of the gender wage gap.

The story is very different in India, where women’s market hours declined sharply over the past two decades despite a decline in the gender wage gap. This points to the growing importance of non-wage factors, or gender wedges, for the gender division of work.

How to achieve a more equitable division of work

Overall, our research documents significant disparities across countries in the gender division of work. While some patterns, such as the U-shape in women’s market work relative to income, are widely recognised, our findings reveal much broader variation across countries—even those with similar income levels. This suggests that social, institutional, and policy choices play a pivotal role in shaping these patterns.

The implications are clear: economic growth on its own does not guarantee convergence in the gender division of work. Policies targeting non-wage factors—incentives for men’s participation in domestic work and dismantling institutional barriers that disproportionately affect women—are essential to achieving a more equitable division of labour.

Editor's note: This paper was featured in the STEG working paper series.

Bick, A, and N Fuchs-Schündeln (2017), “Quantifying the disincentive effects of joint taxation on married women's labor supply,” American Economic Review, 107(5): 100–104.

Boserup, E (1970), Woman’s Role in Economic Development, St. Martin’s Press, New York.

Bursztyn, L, A L González, and D Yanagizawa-Drott (2020), “Misperceived social norms: Women working outside the home in Saudi Arabia,” American Economic Review, 110(10): 2997–3029.

Gottlieb, C, C Doss, D Gollin, and M Poschke (2024), “The gender division of work across countries,” STEG Working Paper, WP95.

Goldin, C (1994), “The U-shaped female labor force function in economic development and economic history,” in Investment in Women’s Human Capital and Economic Development, ed. by T P Schultz, University of Chicago Press, 61–90.

Greenwood, J, A Seshadri, and M Yorukoglu (2005), “Engines of liberation,” The Review of Economic Studies, 72(1): 109–133.

Heath, R, et al. (2024), “Female labor force participation,” VoxDevLit, Vol 11 Issue 1, 28 February. Available at: https://voxdev.org/voxdevlit/female-labour-force-participation.

Inglehart, R, C Haerpfer, A Moreno, C Welzel, K Kizilova, J Diez-Medrano, M Lagos, P Norris, E Ponarin, and B Puranen et al. (2020), “World Values Survey: All rounds – Country-pooled datafile,” Available at: http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWVL.jsp.

Jayachandran, S (2021), “Social norms as a barrier to women’s employment in developing countries,” IMF Economic Review, 69(3): 576–595.

Sinha, J (1965), “Dynamics of female participation in economic activity in a developing economy,” World Population Conference, Belgrade, vol. 4.

Ngai, R, C Olivetti, and B Petrongolo (2024), “Structural transformation over 150 years of women’s and men’s work,” mimeo.

World Bank (2024), “Women, business and the law 2024.”