Reducing tax rates increases tax revenues when enforcement capacity is low. However, low-capacity states can invest in tax enforcement to shift up the revenue-maximising tax rate.

Editor's Note: For more on tax enforcement read the VoxDevLit on Taxation and Development.

Governments in the world’s poorest countries face severe revenue constraints. They collect only 10% of GDP in taxes compared to 40% in rich countries. This lack of government revenue has been associated with low-quality public services and infrastructure and may deter economic growth (Kaldor 1965, Besley and Persson 2013).

Our research (Bergeron, Tourek, and Weigel 2023) examines several randomised tax policy experiments conducted in the Democratic Republic of the Congo to study how tax rates, tax enforcement, and their interaction determine how much tax revenue the government can collect.

Randomised property tax rate reductions in Kananga

To study the effects of tax rates on compliance and revenue, we partnered with the Provincial Government of Kasai-Central, in the DRC, which randomised property tax rate reductions at the property level in 2018 in the city of Kananga.

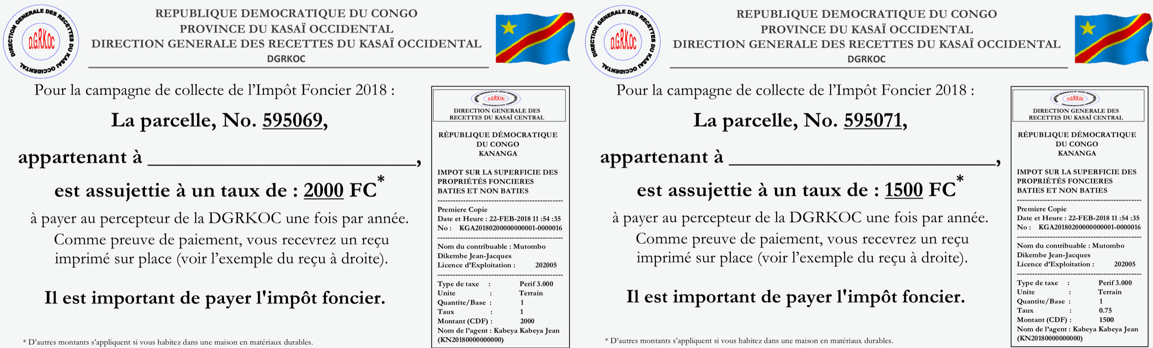

The city’s 38,028 properties were randomly assigned to the status quo annual tax liability (control group) or a reduction of 17%, 33%, or 50% (treatment groups). The tax liability was pre-populated on the tax notices received by property owners during property registration (Figure 1). To our knowledge, this is the first policy experiment to generate random variation in tax liabilities.

Figure 1: Status quo tax liability and tax reductions

Panel A: Status Quo Tax Liability Panel B: 17% Tax Reduction

Panel C: 33% Tax Reduction Panel D: 50% Tax Reduction

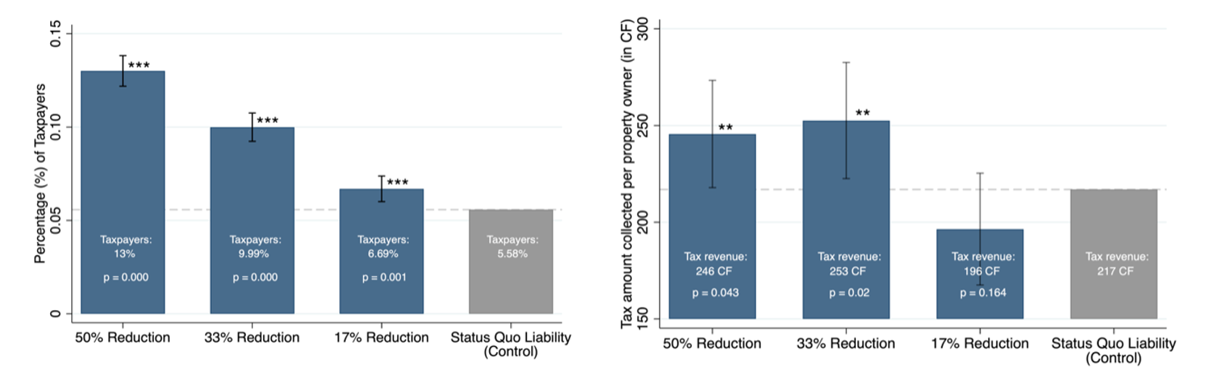

When enforcement is low, reducing tax rates increases tax revenues

As in most low-income countries, tax compliance is low in Kananga. On average, 8.8% of property owners paid the property tax in 2018. However, lowering tax liabilities substantially increased compliance. Only 5.6% of the owners assigned to the status quo tax liability paid the property tax, compared to 6.7%, 10%, and 13% for owners assigned reductions of 17%, 33%, and 50%, respectively (Figure 2, Panel A). The extensive margin tax compliance increase translated into revenue gains at lower tax rates. Tax revenues per property owner were higher for individuals assigned to the 50% and 33% reduction treatment groups than those assigned to the 17% reduction or the status-quo tax rate (Figure 2, Panel B). In sum, status quo tax rates were above the revenue-maximising tax rate in this setting, and the government increased revenue by lowering tax rates.

In our research, we examine the validity of our treatment effects estimates by considering alternative explanations for the large compliance responses to tax rate reductions, including whether property owners were motivated by fairness considerations, the sense of getting a ‘good deal,’ or whether collectors exerted enforcement efforts differentially across rates. We find little evidence supporting these explanations.

Figure 2: Treatment effects on tax compliance and tax revenue

Panel A: Tax Compliance Panel B: Tax Revenue

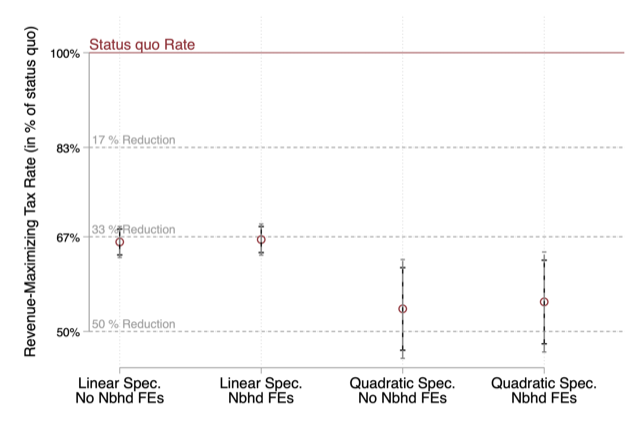

To estimate the exact reduction that would maximise revenue, we outline a simple theoretical framework focused on how tax rates impact citizens’ decision to comply or not with the property tax. This framework generates a formula for the revenue-maximising tax rate that we estimate in the data. Using this approach gives results consistent with the estimated treatment effects of the tax rate reductions: the government would maximise its tax revenue by reducing the status quo tax rate by 34% (Figure 3).

Figure 3: The revenue-maximising tax rate

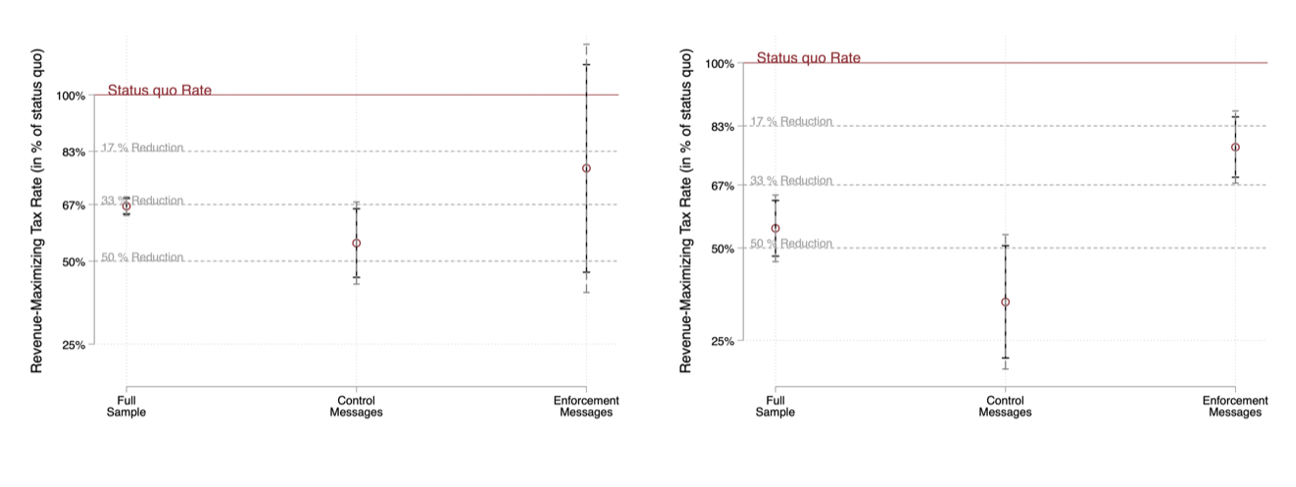

As tax enforcement capacity increases, higher tax rates generate more tax revenue

Do our findings imply that low-capacity states are condemned to setting low tax rates and raising low tax revenue? To investigate, we examine whether investing in enforcement capacity can raise the revenue-maximising tax rate, as our theoretical framework suggests.

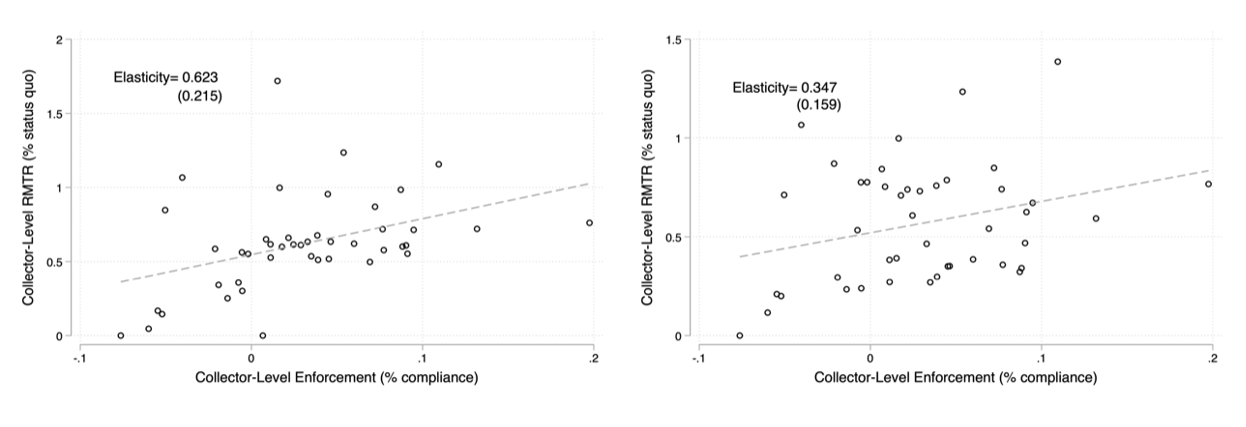

We rely on two sources of variation in enforcement to test this prediction. First, we study randomised enforcement messages embedded in government tax letters distributed by tax collectors to property owners. Property owners either received an enforcement message noting the penalties for tax delinquency - a standard tool for raising compliance (Blumenthal et al. 2001, Pomeranz 2015) - or a control message noting that paying the property tax is important. We estimate that the revenue-maximising tax rate is 41% higher among owners assigned to the enforcement message (Figure 4, Panels A and B).

A second source of variation in enforcement comes from the random assignment of tax collectors to neighbourhoods. Tax collectors vary in their enforcement ability – i.e. their ability to make property owners pay the tax – and we use their random assignment to neighborhoods to estimate how collector enforcement capacity impacted the revenue-maximising tax rate. We use fixed effects models to estimate each collector’s enforcement ability and revenue-maximising tax rate. The tax collector approach yields similar results to the tax letter approach: the revenue-maximising tax rate increases with collector enforcement capacity. Specifically, replacing tax collectors in the bottom quartile of enforcement capacity with average collectors would increase the revenue-maximising rate by 42% (Figure 4, Panels C and D).

Figure 4: Revenue-maximising tax rate by enforcement capacity

Panel A: Tax Letter Variation Panel B: Tax Letter Variation

(Linear Specification) (Quadratic Specification)

Panel A: Tax Collector Variation Panel B: Tax Collector Variation

(Linear Specification) (Quadratic Specification)

Policy and revenue implications

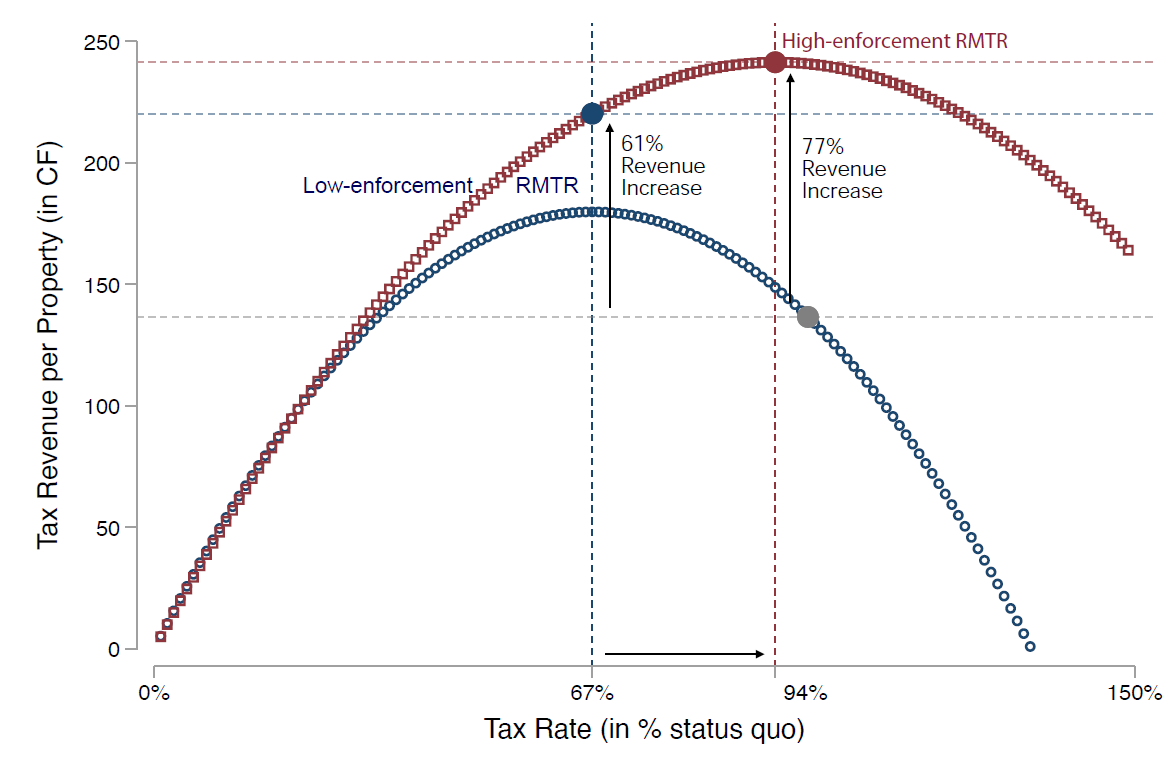

The positive effect of tax enforcement activities on the revenue-maximising tax rate suggests that tax rates and enforcement are complementary policy levers. When tax enforcement is weak, the revenue-maximising tax rate is low because raising rates would lead more taxpayers to become delinquent. However, better tax enforcement attenuates this delinquency response, allowing the government to set higher tax rates.

We illustrate the complementarity between tax rates and enforcement in revenue terms in Figure 5. The government could increase tax revenue by 61% when adjusting tax rates and increasing enforcement independently and by 77% when adjusting them jointly.

Tax authorities in low-income countries face enormous constraints. Anticipating this complementarity between tax rates and tax enforcement can help them expand their revenue potential.

Figure 5: Tax rates and enforcement as complements revenue implications

References

Kaldor, N (1965), “The Role of Taxation in Economic Development” in Problems in Economic Development, Springer, pp. 170-195.

Besley, T, and T Persson (2013), “Taxation and Development” in Handbook of Public Economics, Elsevier, 51-110.

Bergeron, A, G Tourek, and J Weigel (2023), “The State Capacity Ceiling on Tax Rates: Evidence from Randomized Tax Abatements in the DRC”, Conditionally Accepted, Econometrica.

Blumenthal, M, C Christian, and J Slemrod (2001), “Do Normative Appeals Affect Tax Compliance? Evidence from a Controlled Experiment in Minnesota”, National Tax Journal, 54(1): 125-138.

Pomeranz, D (2015) “No Taxation without Information: Deterrence and Self-Enforcement in the Value Added Tax”, American Economic Review, 105(8): 2539-69.