Unemployment insurance (UI) in Senegal can provide significant welfare gains, but given high levels of informality and a lack of transparency about workers’ status, these gains depend on programme design. UI funded through payroll taxes is effective and feasible as long as the ratio of formal workers to the benefit level is sufficiently high, while UI funded through consumption taxes generally offers lower welfare benefits but is more robust to fraudulent claims.

Unemployment Insurance in Africa

Wage earners in low-income African economies frequently serve as the financial backbone for a broad network of economic agents, providing insurance for their kin and peers against shocks, facilitating transfers to extended family, and fostering economic relief (Cox and Fafchamps 2007). The high dependency of unemployed individuals on private transfers from wage earners highlights the need for worker protection, as stressed by recent major labour market shocks. Unemployment Insurance (UI) is one form of worker protection programme whose prevalence is considerably low in low-income because of the difficulties in tracking work statuses and funding UI budgets (Benjamin and Mbaye 2012, Cirelli et al. 2021).

The enthusiasm for UI as a macroprudential policy tool fades in the face of challenges related to funding, labour force composition and eligibility criteria. The scarcity of empirical evidence due to the limited instances of UI adoption in low-income countries and the absence of high-frequency labour force surveys complicates the task of addressing concerns about the feasibility of UI schemes in Sub-Saharan Africa. In our research (Ndiaye et al. 2024), we study the Senegalese labour force survey to advance our understanding of the impact and optimal design of UI in labour markets characterised by low formality and by the presence of informal workers who might submit fraudulent claims to qualify for UI benefits.

Five key facts about Senegal’s labour market

We use nationally representative living standard and labour force surveys to document five key characteristics of the Senegalese labour market.

- Most workers are informal, with only a small fraction of workers and firms being formally established.

- Even within formal firms, there is a substantial presence of undeclared informal workers, who could falsely claim UI targeted toward formal workers.

- There are pronounced income, consumption, and asset disparities across different employment statuses and, therefore, high potential for consumption smoothing through social insurance.

- Even within formal employment settings, a majority of workers lack significant work-related benefits, highlighting the need for a more robust social safety net.

- Informal networks are a significant form of insurance for workers.

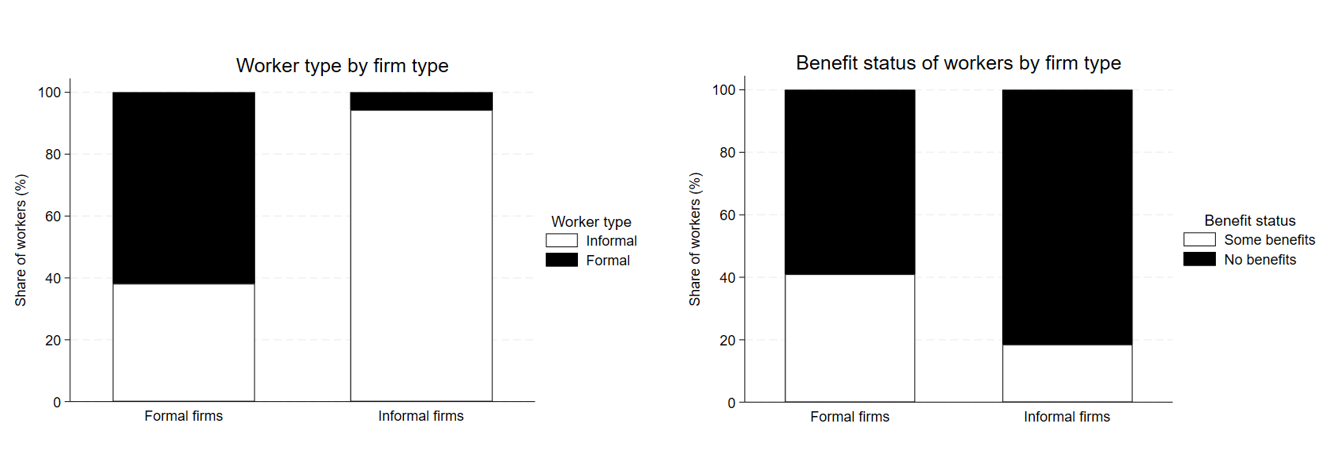

Figure 1: Worker type and benefit level, by firm formality type

Notes: Work benefits include transportation subsidies, meal subsidies, paid vacation, sick days, pension, severance pay, overtime pay, health insurance, performance pay, training, work security, childcare, maternal/paternal leave, and work accident insurance. The category ``Some benefits'' refers to workers who receive at least one of the above benefits, while the category ``No benefits'' represents workers with none of the benefits. Informal workers are workers with no formal, written work contract. Informal firms are firms with no formal accounting system and no formal registration. The analysis sample includes only individuals in the labour force.

A model of unemployment insurance calibrated with a custom labour force survey

We extend the Chetty (2006) model by allowing informal workers to collect UI benefits while working and by distinguishing work statuses among informal employment, formal employment, and unemployment. We consider three different schemes with varying degrees of enforcement and funding sources:

- a model with a standard payroll tax-funded UI system in which only formal workers contribute to funding the UI programme, and a share of informal workers can fraudulently claim benefits (model I)

- a model with a perfect enforcement of employment status, UI contributions on employed workers, and no false claims from informal workers (model II)

- a model where the UI system is funded by a consumption tax, and formal, informal, and unemployed workers all pay the consumption tax and thus contribute to funding UI (model III).

We explore the welfare effects of UI expansions in each of these three models. Our theory emphasises that in the presence of informal work and limited enforcement of eligibility criteria, funding constraints for standard payroll tax-funded UI systems can be significantly binding.

We then conduct a highly customised in-person labour force survey in Senegal with 1378 individuals to estimate the model. Our survey is representative of the major labour market in Senegal and departs from typical labour force surveys in our context since it was specifically designed to allow us to calibrate the key parameters identified in our conceptual framework:

- Elasticities of job search and job quit rates with respect to the benefit level for each work state

- Consumption levels by employment status

- Workers' risk aversion

- The degree of informal work and enforcement

After estimating these parameters, we provide welfare estimates for the value of UI and assess the relative importance of moral hazard versus liquidity constraints.

The returns to different unemployment insurance schemes in the Senegalese labour market

UI can offer a robust safety net even in economies characterised by high informality and an increased risk of false claims. An extra dollar of UI benefits yields a consumption-equivalent gain of over 80 cents under the payroll tax-funded scheme (Models I & II) and over 50 cents under the consumption tax-funded scheme (Model III). The magnitude of the dollar consumption gain to an unemployed worker per dollar of benefits – the ``dollar-on-dollar'' welfare metric – significantly exceeds that for the U.S., where an extra dollar of UI is estimated to yield a consumption-equivalent gain of approximately 4 cents (Chetty 2006). In other words, the gains from a small UI expansion would be approximately 10 to 20 times larger in Senegal than in the U.S.

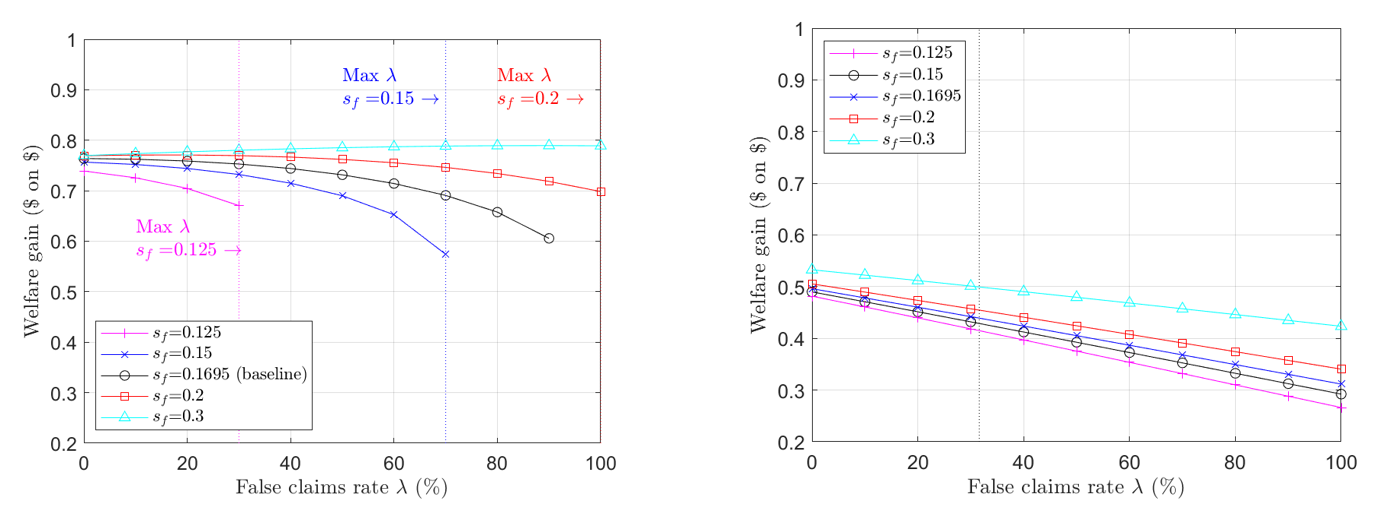

Figure 2: Unemployed worker’s dollar consumption gain per dollar of benefits under different levels of false claims and different levels of formal employment

Notes: The figure shows the effects of a change in the unemployed worker’s dollar consumption gain per dollar of benefits with changes in the share of informal workers who manage to access UI (λ) for different levels of formal employment. The left plot represents the gains with a payroll tax-funded UI system, in which the tax is paid by formally employed workers only; the right plot represents the gains with a consumption tax financing scheme.

Figure 2 shows the change in dollar-on-dollar gains under different false claim rates and different levels of formality. First, regarding false claim rates, we observe that the payroll tax financing scheme delivers greater welfare gains for lower levels of false claims. However, the tax burden becomes so large at high levels of false claims that a payroll tax system eventually becomes infeasible. Alternatively, a UI system funded through VAT or consumption taxes, while generally offering lower welfare benefits than a payroll tax-funded system, remains feasible even when fraudulent claims are severe. It has a broader base and ensures a minimum welfare level under the most adverse conditions. Second, regarding formality level, we note that at levels of formal employment lower than those reported in our survey, the tax burden on formal workers is so large that, even with low levels of false claims, the payroll tax-funded UI scheme might be infeasible. In these scenarios, consumption tax financing is less effective but remains feasible because of the reduced moral hazard effects. Conversely, as the economy becomes more formalised, we observe the standard outcome of a payroll tax being the most efficient instrument to finance UI.

Takeaways on funding unemployment insurance for policymakers and researchers

In economies where the government can not effectively differentiate between informal employment and unemployment, the cost of financing and monitoring UI can become prohibitively high. A UI scheme funded by payroll taxes can become unfeasible at high false claim rates, if the share of formal workers relative to benefits is low. In economies with a significant informal sector, financing a UI policy with a broad tax emerges as a viable compromise. This approach mitigates the moral hazard effect associated with payroll financing and is robust against the potential infeasibility of UI that may arise with a high payroll tax on a small formal base. Once the economy achieves a higher level of formalisation, characterised by an increased taxable base and a reduced share of false claimants, the payroll tax financing scheme surpasses the consumption tax in efficiency, in line with findings obtained for economies with negligible levels of informality.

We highlight caveats of our analysis and avenues for future research. First, our data cover only urban areas and we do not directly model the large share of agricultural workers that typically characterise low-income countries. Second, dynamic aspects of the labour market are important features to capture in the design of unemployment insurance, as highlighted by Liepmann and Pignatti (2024). Third, we do not model other potential insurance policies such as cash transfers and progressive taxation.

Editor’s note: Check out our VoxDevLit on Informality for a broader summary of economic research relevant to this topic.

References

Benjamin, N and A A Mbaye (2012), The Informal Sector in Francophone Africa, The World Bank.

Breza, E, S Kaur, and Y Shamdasani (2021), “Labor Rationing,” American Economic Review, 111(10): 3184–3224.

Chetty, R (2006), “A general formula for the optimal level of social insurance,” Journal of Public Economics, 90(10): 1879–1901.

Cirelli, F, E Espino, and J M Sanchez (2021), “Designing unemployment insurance for developing countries,” Journal of Development Economics, 148: 102565.

Cox, D and M Fafchamps (2007), “Extended family and kinship networks: economic insights and evolutionary directions,” Handbook of Development Economics, 4: 3711–3784.

Liepmann, H and C Pignatti (2024), “Welfare Effects of Unemployment Benefits When Informality Is High,” Journal of Public Economics, 229: 105032.

Ndiaye, A, K F Herkenhoff, A Cisse, A Dell'Acqua, and A A Mbaye (2023), “How to Fund Unemployment Insurance with Informality and False Claims: Evidence from Senegal,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper #31571.