Shrinking school–parent information gaps through text messaging can be an effective way to improve grades and attendance outcomes for schoolchildren

Grade retention and early dropout are two of the greatest challenges facing education systems in middle-income countries. In Latin America, only 52% of students graduate from high school on time, and only 66% of individuals aged 20–25 who have completed primary school graduate from secondary school (Busso et al. 2017). Researchers have identified absenteeism, failing grades, and classroom misbehaviour in middle school and in earlier grades as strong predictors of grade retention and the probability of dropout (Balfanz et al. 2007, Manacorda 2012, Wedonoja 2017). While schools around the world routinely record these early warning outcomes, families often do not have timely access to this information. Without such information, parents may be limited in their ability to work with young adolescents and schools to reduce absenteeism and improve grades.

Recent work in the US has shown that low-cost communication technologies can bridge such information gaps between schools and parents, and positively affect student outcomes (Bergman 2021, Bergman and Chan 2019; see Escueta et al. 2020 for a review of recent studies). Can similar communication strategies address information gaps and improve education outcomes in settings with far fewer school resources? In a recent paper (Berlinski, Busso, Dinkelman, and Martínez A. 2021), we set out to answer this question.

Using text messages to connect parents with schools in real time

We conducted an experiment in low-income schools in Chile to test the effects and behavioural changes triggered by a programme, Papas al Día, that sends information on attendance, grades, and classroom behaviour to parents via weekly and monthly text messages. Our intervention included around 1,000 students enrolled in one of fourth through eighth grades in seven low-income schools in a metropolitan area in Chile. The median student is 10 years old.

The experiment targets parents during the years when students’ attendance and grades start to matter, but before the risks of grade repetition or dropout significantly increase. Papas al Día was deliberately designed to test a low-touch, low-cost intervention that could be easily and inexpensively implemented at scale. We did not teach parents how to interpret or use the information, nor did we provide guidance to students, teachers, or principals.

Randomisation into treatment or control status was at the classroom level, with some treated classrooms randomised into having a high share (75%) of students treated and other treated classrooms randomised into a low-share (25%) treatment. Treated parents received (separate) weekly messages on attendance and monthly messages on classroom behaviour and maths test scores. All parents received general messages about school matters throughout the year, and both control and treatment parents continued to receive report cards each quarter, as is typical in Chile.

During the two school years of the intervention, we sent over 44,000 text messages to parents at different frequencies (weekly and monthly). Since we randomly manipulated the share of treated students in each classroom, we can also quantify spill-over effects of the treatment within classrooms.

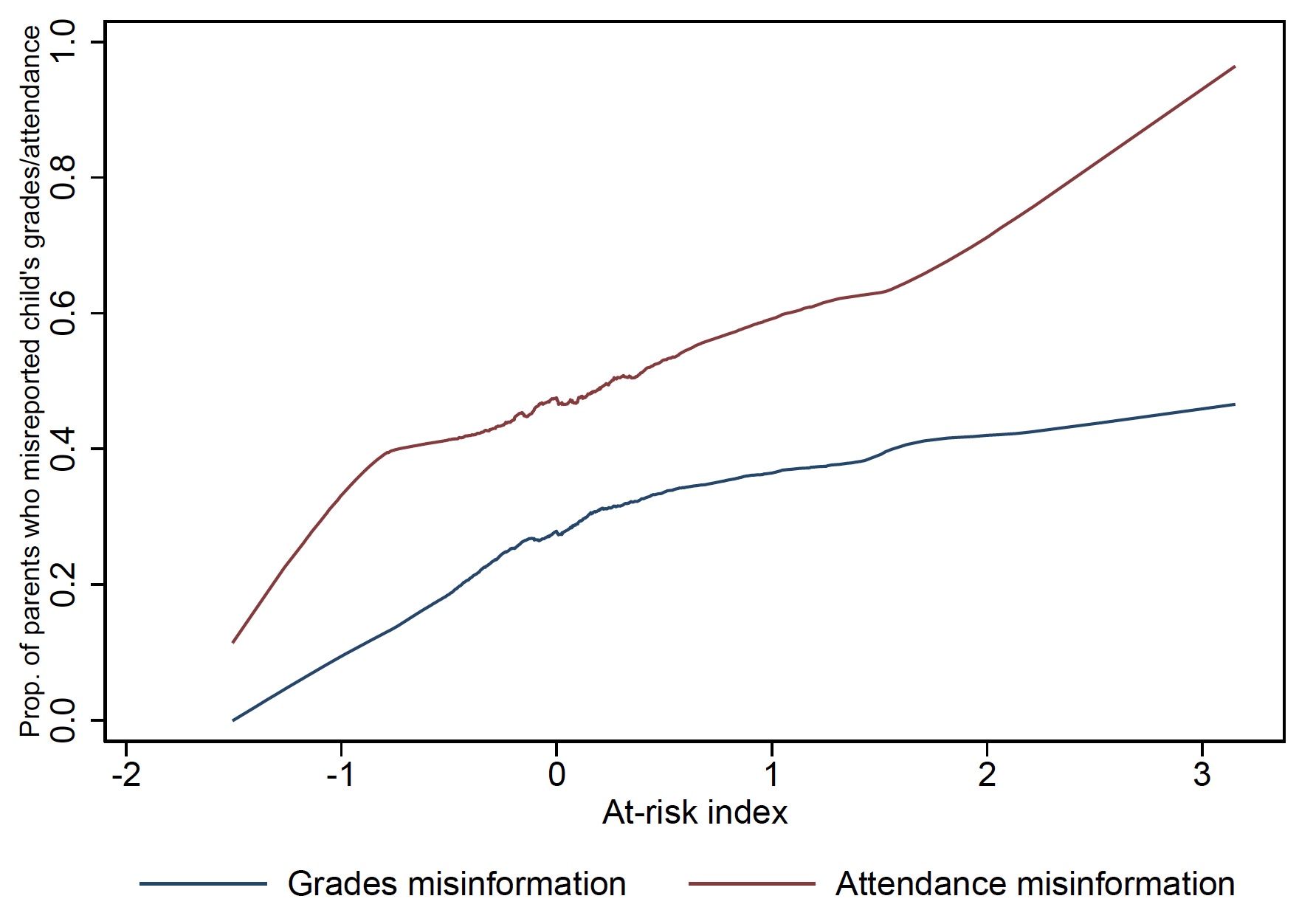

Misinformation is greatest among parents of the most at-risk students

Our baseline survey data shows that parent misinformation is widespread. About one in four parents was unable to report correct information about a child's grades and attendance. Figure 1 plots the share of parents whose report of the child's grade/attendance was at odds with the child's actual school performance before the intervention began. This misreporting share is plotted against a summary measure — the at-risk index1 — of whether a child is considered at risk of retention or dropping out (because of higher absenteeism, lower grades, or worse behaviour in class) before the intervention.

For students with the highest values of the at-risk index, over 80% of the parents were misinformed about attendance (red line) and about half had incorrect information about grades (blue line). These are the gaps that our information intervention is designed to shrink.

Figure 1 Baseline share of misinformed parents

Note: Y-axis presents the (lowness-smoothed) share of parents misinformed regarding their child's grades and attendance as measured by the at-risk index. Based on parent surveys at baseline.

Our first finding is that the text message treatment does shrink information gaps between parents and schools, although the effects are most pronounced and statistically significant for attendance outcomes, and weaker for grade outcomes. Parents of at-risk students ‘correct’ their understanding of their child's performance to the greatest degree, although results are not statistically significant at normal levels.

Attendance and maths scores improve after Papas al Día, with largest gains among at-risk students and positive spillovers within classrooms

Papas al Día had positive impacts on grades and attendance. A comparison of the treated and control students shows that the intervention led to an increase in maths GPA of 0.09 of a standard deviation; the probability of earning a passing grade in maths increased by 2.7 percentage points. The intervention also reduced school absenteeism by 1 percentage point and increased the share of students who satisfied the attendance requirements for grade promotion by 4.5 percentage points.

Exploiting the randomised variation in the share of students treated within a classroom, we examine whether there is extra value in being in the text-messaging programme when many more classmates are also in the programme. Such spillovers could be important, especially if such parent-school communication programmes scale up to cover all enrolled students. In all cases, the differential effect of being assigned to treatment in a high-share treated classroom improves educational outcomes of treated students — indeed, it is larger than the main effect of the treatment in low-share classrooms. This suggests that our results are probably lower bounds on impacts at scale.

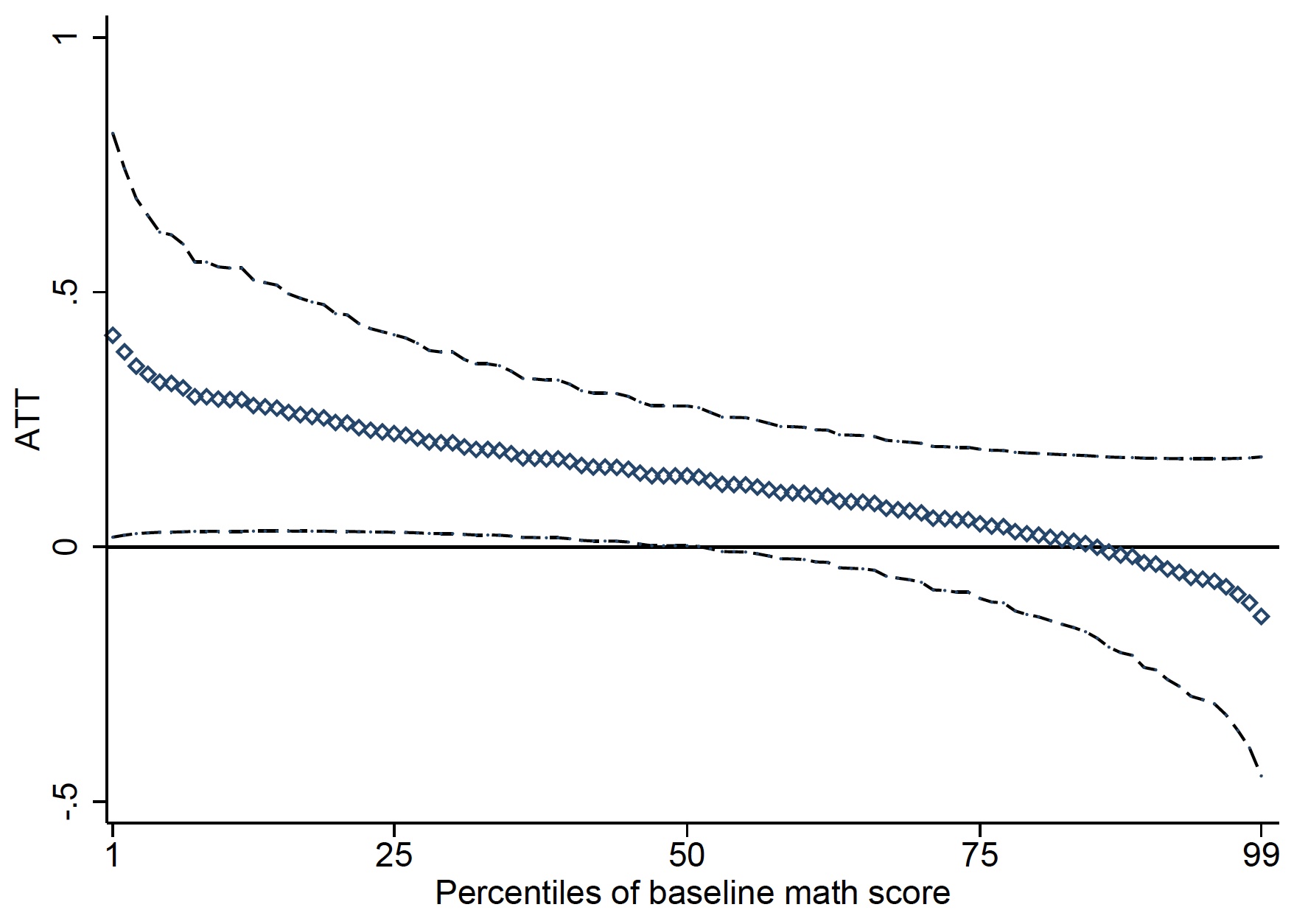

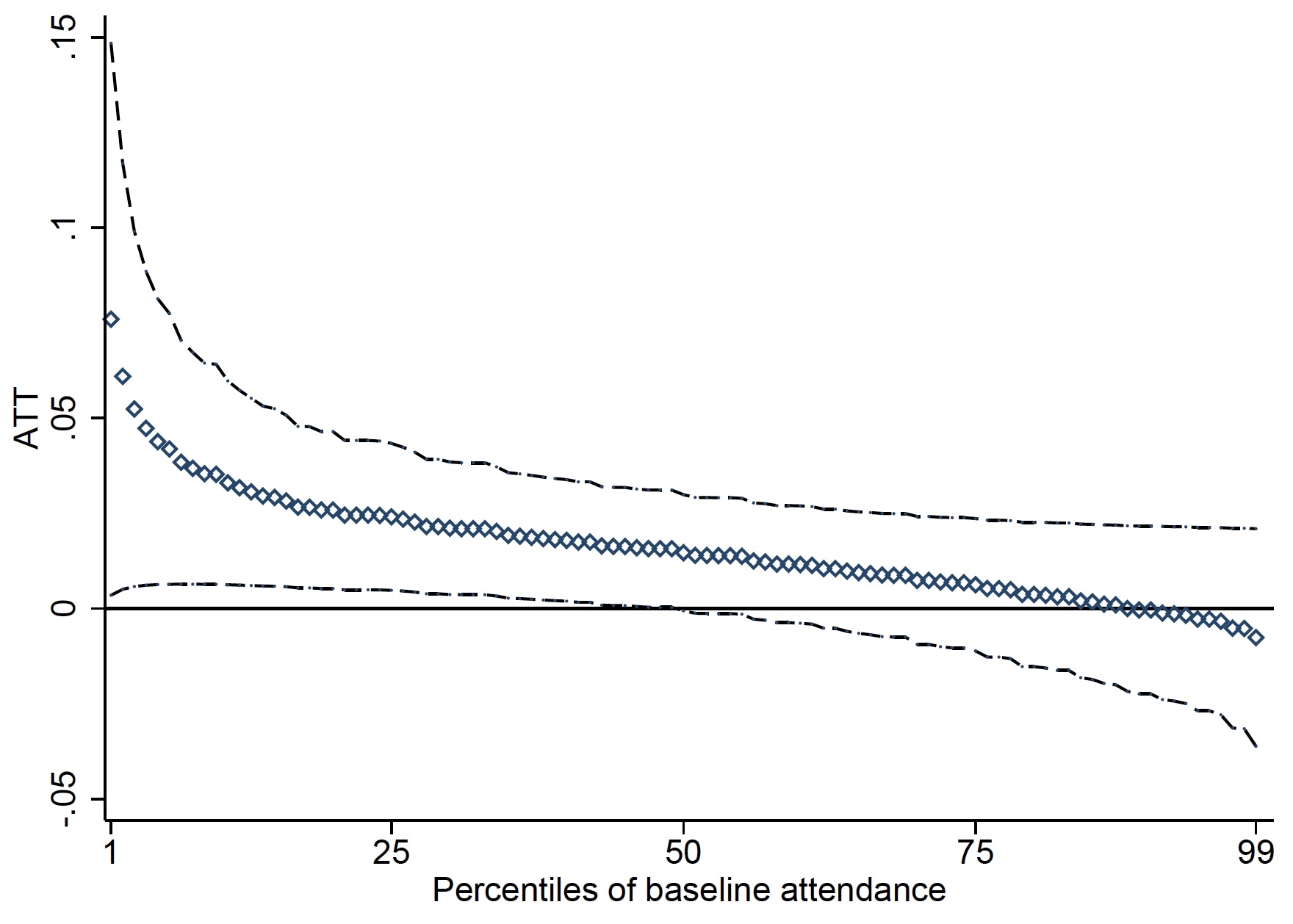

Figure 2 illustrates that treatment effects are heterogeneous with respect to baseline outcomes and are larger for students at higher risk of later grade retention and dropout. Each graph plots the estimated intent-to-treat estimates and 95% confidence intervals for outcomes of maths scores (Panel A) or attendance (Panel B) at the end of the experiment against baseline maths scores or attendance. Effects are largest for those with the lowest initial maths grades and attendance rates.

Figure 2 Predicted treatment effects by baseline characteristics

Panel A: Maths score

Panel B: Attendance rate

Note: Figure shows linear predictions and 95% confidence intervals of the intent-to-treat estimates on maths grades and attendance rate.

How did shrinking parent-school information gaps translate into better attendance and higher grades? Baseline and follow-up survey data from parents and students indicate that the intervention changed parent behaviours at home. Treated students perceived that they received significantly more family support after the intervention, and students perceived that their parents were more involved in school matters. Consistent with these changes in parental behaviour, we use evidence from a survey experiment conducted while following up to show that some treated parents, especially those of at-risk students, are willing to pay for the information. We interpret this as parents learning about the value of the information provided in Papas al Día.2

Implications for policy: Deploy school information to parents at scale and on the cheap

Our study shows that in low-income schools in Chile, when parents are more in the know, they are better able to ‘mind the information gap’ and support their children in school, leading to improved school outcomes. Low-performing at-risk students benefited the most from receiving the Papas al Día intervention. The results from our study (and others) underscore how the lack of correct and timely information can be a significant constraint to decision-making.

Papas al Día was a highly cost-effective programme: a 0.01 standard deviation increase in math scores had a variable cost of about US$1.18 per student per year at market prices. This rises to US$ 2 per student per year when we include the fixed setup costs. Moreover, the text-messaging programme has strong potential for scalability. The great deal of data that schools around the world already collect on students is low-hanging fruit that can be digitised and provided to parents frequently and regularly. Where school resources are limited and improving school quality is a challenge, low-cost SMS messaging offers an effective and relatively inexpensive way to improve grades and attendance outcomes.

References

Balfanz, R, L Herzog and D J Mac Iver (2007), "Preventing student disengagement and keeping students on the graduation path in urban middle-grades schools: Early identification and effective interventions", Educational Psychologist, 42(4), 223-235.

Bergman, P (2021), "Parent-child information frictions and human capital investment: Evidence from a field experiment", Journal of Political Economy, 129(1).

Bergman, P and E W Chan (2019), "Leveraging parents through low-cost technology: The impact of high-frequency information on student achievement", Journal of Human Resources, 56(1), 125-158.

Berlinski, S, M Busso, T Dinkelman and C Martínez (2021), "Reducing Parent-School Information Gaps and Improving Education Outcomes: Evidence from High-Frequency Text Messages", NBER Working Paper 28581.

Busso, M, J Cristia, D Hincapié, J Messina and L Ripani (Eds.) (2017), Learning Better: public policy for skills development, Inter-American Development Bank.

Escueta, M, A J Nickow, P Oreopoulos and V Quan (2020), "Upgrading education with technology: Insights from experimental research", Journal of Economic Literature, 58(4), 897-996.

Manacorda, M (2012), "The cost of grade retention", Review of Economics and Statistics, 94(2), 596-606.

Wedenoja, L (2016), "The dynamics of high school dropout", Job Market Paper, Cornell University.

Endnotes

1 To create the at-risk index, we take the average of standardised attendance, standardised math grades, and negative behavioural notes from teachers. We measure these three variables before the intervention starts.

2 While following up, we randomly assigned to parents in both treatment and control groups a monthly price for receiving future Papas al Día messaging. Demand for the service slopes down for all parents, and parents in the treatment group whose children were initially at higher risk of grade retention and dropout are significantly more likely to say they are willing to pay for the continued service relative to control parents.