Voters that received information about municipal education outcomes in Chile punished mayors with poor performance at the ballot box.

Elections are the key institution of democracy. Citizens exercise political control by electing their representatives and holding them accountable for their performance. However, poor governance abounds, and it often does with electoral support (e.g. Olken and Pande 2013). Why does this happen? Past studies have hypothesised that citizens may lack information to adequately assess their leaders. Several experiments have tested this hypothesis, often with a focus on corruption (e.g. Ferraz and Finan 2008, de Figueiredo et al. 2023, Chong et al 2015, Larreguy et al. 2020), and the findings are mixed. This raises the question of whether the effects of information depend on the policy area or on how information is provided.

Providing voters in Chile with information about local government outcomes

We conducted a large-scale randomised experiment to explore the electoral effect of providing voters with information about local government outcomes – in this case, educational outcomes. We study the case of Chile, an emerging country with a consolidated democracy, where local governments oversee the management of public schools and voters identify the provision of education as one of their main priorities. Additionally, the experiment included different treatments to better understand what types of information matter to voters.

The intervention consisted of sending voters a letter with information about the educational outcomes of public schools in their municipality during the tenure of the current mayor, one week before the municipal election on October 23, 2016. The letter provided information on both score levels and changes in scores.

Measuring local government performance on education in Chile

The test scores in level were computed by averaging the language and math test scores of a national assessment taken annually by all fourth-grade students in the country for 2013—2015, which corresponds to three-fourths of the current mayor´s term in office (data for 2016 was unavailable). We corrected the test scores by municipality controlling for a set of socioeconomic and demographic characteristics to make them comparable across municipalities. The changes in test scores were estimated by calculating the difference between the raw average scores for 2013—2015 and those for the previous mayoral period (2009-2012).

Test scores were corrected by controlling for a set of socioeconomic and demographic characteristics to make them comparable across municipalities. The correlation between the information on levels and changes is 0.13 highlighting the importance of presenting both measures, as they provide different insights. Moreover, neither measure correlates with the political affiliation of the mayor indicating that the experimental design was not politically biased.

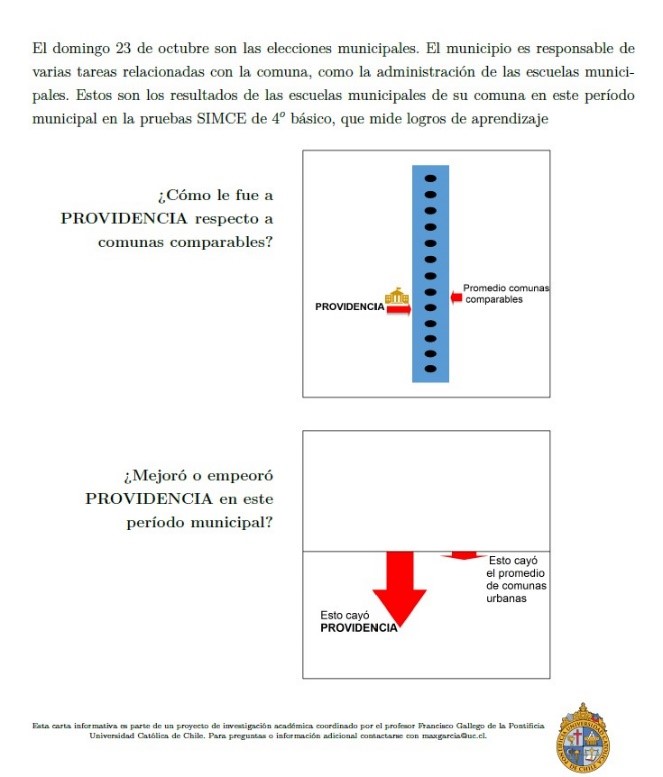

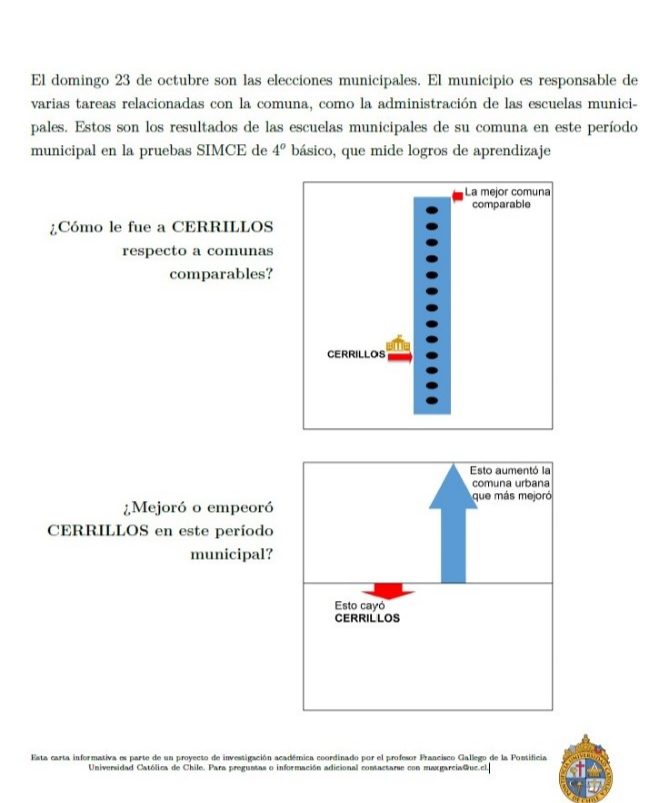

We also varied the benchmark used to compare the municipality´s outcomes for both indicators (levels and changes): average or maximum treatment. The average treatment compared the municipality performance with the municipalities´ average performance. The maximum treatment compared the municipality performance with the best-performing municipality´s results. The information in the letter was shown visually, with simple graphs displaying the municipality´s performance and that of the benchmark (average or maximum), as depicted in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1: Average Treatment

Figure 2: Maximum Treatment

Note: Figure 1 shows that the municipality ‘Providencia’ was just below the municipality average for the level (2013-2015) test performance measure and test performance fell between the two periods (2013-2015 vs 2009-2012) by more than the average municipality. Figure 2 shows the same idea but for the municipality of Cerrillos and compared to the best performing municipality in both levels and changes.

Our sample included 59 large, urban municipalities in Chile, where the current mayor was running for reelection. The experiment was conducted at the polling station level, covering 22,387 stations, with an average of 329 registered voters each. The electoral roll was public at the time, including voters’ addresses. Thus, we sent letters to all voters in 400 randomly selected polling stations, half and half with each treatment. Overall, we sent letters to more than 128,000 voters.

Voters punish mayors who are performing poorly

Our experiment reveals four main findings. First, information is important for political accountability. Information conveying poor relative performance in education reduces electoral participation, which translates into an equivalent reduction in the incumbent’s vote share: voters punish mayors’ poor performance by not turning out to vote for them. The size of this effect is significant: a shift from the 75th to the 25th percentile in educational performance is associated with a reduction in turnout of about 1.35 percentage points and a decrease in the support for the incumbent of around 1.23 percentage points. The support for the challenger was unaffected by the treatment.

Second, not all information is equally influential. The way in which information is presented plays a crucial role. The effects were only significant for the average treatment. There were no statistically significant effects for the letter with a more stringent benchmark (best-performing municipality). The results also indicate that voters respond to information about outcomes in levels, rather than to changes in outcomes. Additionally, our results were asymmetric: voters respond much more to “bad” outcomes than to “good” ones, consistent with loss aversion and with previous research (Cruz et al. 2021, Kahneman and Tversky 1979).

Third, voters’ prior beliefs influence their responses to new information. We create a proxy for perceptions of school quality at the polling station level, based on a survey conducted with the parents of all fourth-grade students who take the national assessment. We find that information is more impactful when it comes as “news” in the sense that it was unexpected, consistent with Arias et al. (2022) and Gallego et al. (2020). Also, again in line with loss aversion, voters react more strongly to “bad” than to “good news” (i.e. to priors of better performance than actual results).

Finally, we analyse whether the effect of the information varies based on the municipalities’ characteristics. Although the differences are not statistically significant, we find suggestive evidence that the effect of information is greater in poorer municipalities, and in those with lower levels of incumbent campaign spending, suggesting greater impact where information is scarcer. We also find that our main effects were partially transferred to the concurrent election of the municipal council members.

Policy implications of providing information to voters

Our results show that receiving information about poor relative performance decreases turnout, which closely corresponds to a drop-in support for the incumbent. These effects are concentrated on letters that use average performance as a benchmark, and in levels rather than in changes. The results are especially strong when bad educational results come as a surprise compared to voters’ prior beliefs. These results appear to be stronger in poorer municipalities, and in municipalities with low levels of electoral spending by the incumbent, and spill over to the election of municipal council members.

It is worth noting, however, that we find a series of zero effects on electoral outcomes: no effects of information on score changes, no effects from the maximum treatment, no effects from good results or good news, and no effects on support for the challenger. From a policy perspective, this suggests that it is difficult to use information to affect voters’ behaviour. Moreover, the fact that our significant effects only operate through votes for the incumbent and have no effect on voting for the main challenger implies that political competition has a limited ability to hold incumbents accountable. And since our effects operate via turnout, bad news is demobilising, which may also be problematic, especially in contexts of voluntary voting.

In terms of policy evaluation and policy implications, our experiment incurred a cost of USD$0.34 per voter contacted. This is an upper bound, as information campaigns via social networks, influential figures, or public signage could exploit spillovers to enhance the cost effectiveness of the intervention. While more research is needed, our findings show that although not all information matters for voters, relevant information can elicit a significant response in the polls. Thus, information can potentially improve both governance and education.

References

Arias, E, H Larreguy, J Marshall, and P Querubin (2022), “Priors rule: When do malfeasance revelations help or hurt incumbent parties?” Journal of European Economic Association, 20(4): 1433–1477.

Chong, A, A De La O, D Karlan, and L Wantchekon (2015), “Does corruption information inspire the fight or quash the hope? A field experiment in Mexico on voter turnout, choice, and party identification,” Journal of Politics, 77(1): 55–71.

Cox, L, F Gallego, S Eyzaguirre, and M Garcia (2024), “Punishing mayors who fail the test: How do voters respond to information on educational outcomes?” Journal of Development Economics, 171.

Cruz, C, P Keefer, and J Labonne (2021), “Buying informed voters: New effects of information on voters and candidates,” Economic Journal, 131(635): 1105–1134.

de Figueiredo, M F P, F D Hidalgo, and Y Kasahara (2023), “When do voters punish corrupt politicians? Experimental evidence from a field and survey experiment,” British Journal of Political Science, 53(2): 728–739. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123421000727.

Ferraz, C and F Finan (2008), “Exposing corrupt politicians: The effects of Brazil’s publicly released audits on electoral outcomes,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(2): 703–745.

Gallego, F (2013), “When does inter-school competition matter? Evidence from the Chilean 'voucher' system,” B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 13(2): 525–562.

Kahneman, D and A Tversky (1979), “Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk,” Econometrica, 47(2): 263–292.

Larreguy, H, J Marshall, and J Snyder (2020), “Publicizing malfeasance: When media facilitates electoral accountability in Mexico,” Economic Journal, 130(631): 2291–2327.

Olken, B and R Pande (2013), “Governance Initiative Review Paper,” The Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab Working Paper.