New evidence from El Salvador shows that a short online training programme focused on improving engagement with freelancing platforms can help individuals get onto the platforms and land their first contracts. However, this training alone is unlikely to be enough to generate sustained success.

Editor’s Note: For more research on training entrepreneurs read the VoxDevLit on this topic.

Online gig jobs, where workers are paid per task, now represent a notable portion of the global labour force, with an estimated 154–435 million people engaged in these roles (Datta et al. 2023). Online freelancing, a form of gig work that typically involves intermediate- to high-skill tasks such as graphic design and software development, has become an increasingly popular choice among skilled workers worldwide, offering job opportunities that bypass geographic limits (Kässi et al. 2021). For developing countries like El Salvador, where formal job opportunities are limited, online freelancing could offer a promising path to increase access to high-quality jobs (Lehdonvirta et al. 2019).

Despite its potential, most individuals never manage to successfully obtain online work, particularly in developing countries (Hilbert and Lu 2020). A key question is whether people already have the technical skills needed to compete on online platforms, but need help learning how to get onto such platforms and get contracts, or whether they also need more extensive training on technical skills.

To assess this, we conducted a randomised controlled trial of a 12-week job training programme designed by the Ministry of the Economy of El Salvador, in partnership with the Inter-American Development Bank and Wisar (Fazio et al. 2025). The training was designed to orientate potential online freelancers to the specific tasks required to engage with online marketplaces and successfully work as a freelancer.

Why might people need help engaging with online freelancing platforms?

Online labour marketplaces differ from their traditional counterparts in several important aspects, including the hiring process (Chan and Wang 2018). Employers on online platforms typically assess freelance applicants based on profile information, such as ratings, reviews, and self-declared credentials, as well as through initial communication, such as written proposals and interviews.

Consequently, individuals need specific entrepreneurial skills to successfully secure online work. For example, workers must understand how to navigate the platforms, communicate effectively with clients, and build a strong profile. Language can also be a critical barrier to accessing online opportunities (Datta et al. 2023), as the global supply of online gig work is dominated by workers from English-speaking countries. Together, these additional barriers may prevent individuals from finding online work, even if they possess the necessary technical skills.

Experimentally assessing the impacts of job training to improve online engagement

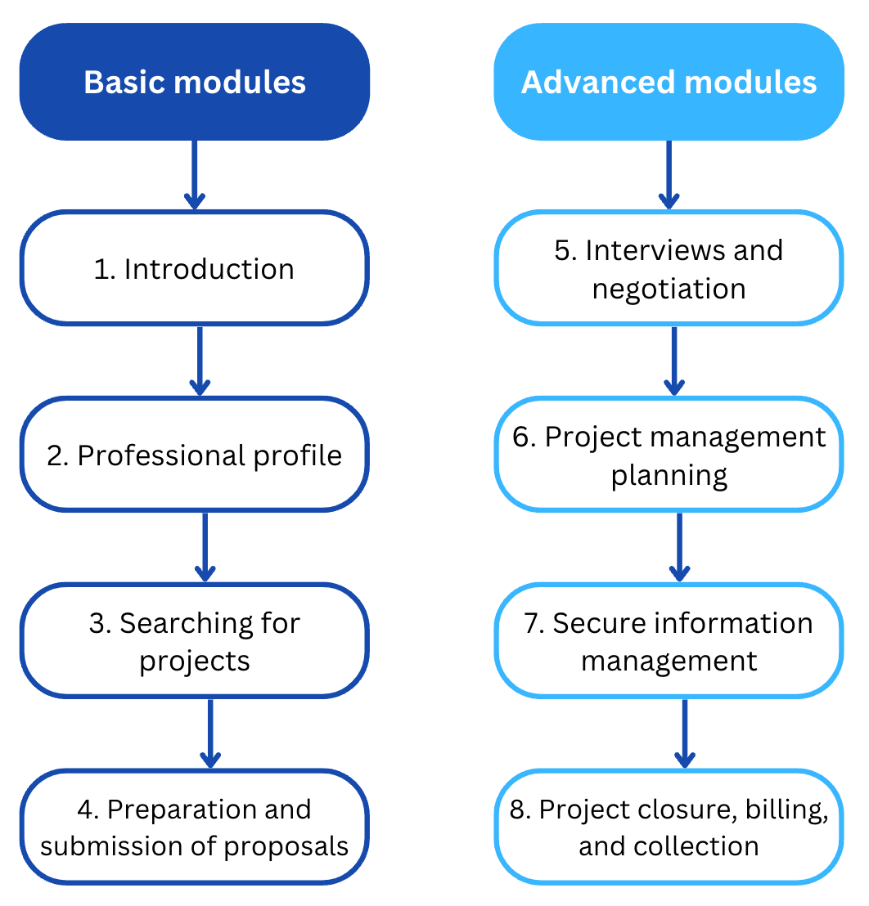

Our experiment evaluates the effectiveness of a 12-week job training programme, consisting of roughly five hours per week, aimed at improving participants’ ability to navigate and engage with online freelancing platforms. The training was structured in two phases: an initial theoretical phase covering eight modules (see Figure 1), followed by a practical phase allowing participants to apply their learning. Additionally, participants had access to an ‘English for Freelancers’ course that included industry-specific jargon, CV tips, and more. All instruction was delivered fully online and asynchronously, but each participant was assigned a tutor to support comprehension.

Figure 1: Training modules

We recruited participants through online marketing, requiring that individuals either hold a technical college or university degree, be in their final year of study, or have at least two years of equivalent experience in fields such as web and mobile development, digital marketing, or graphic design. Additionally, all participants needed to demonstrate at least an intermediate level of English proficiency. Our sample comprised 711 individuals with an average age of 30, of whom 55% are women. We then randomly allocated participants to:

- A control group of 344 individuals plus a waitlist of 17 who could be used if treated individuals didn’t take-up the programme.

- A treatment group of 350 individuals who were offered the training free of charge.

We measured outcomes through administrative data on the treatment group and through a one-year phone follow-up survey.

Key findings from offering a job training programme in El Salvador

1. It is difficult to get people to take-up and complete the online training.

Despite participants self-selecting into the course, being assigned a tutor, and facing no financial cost, completion rates were relatively low. Only 39% of treated participants completed the theoretical phase, 16% completed the full programme, and while 45% started the English course, only 16% completed it.

Additionally, completers tended to come from significantly wealthier households and were less likely to be married, suggesting that economic and household constraints likely affect one’s ability to complete the training.

2. The training does get more people onto the online freelancing platforms and getting a first contract.

Despite relatively low completion rates, the training had positive effects on online freelancing outcomes. At follow-up, 51% of the control group had an online freelancing profile, and 11% signed at least one job contract in the past year. Assignment to the training significantly increased the likelihood of having a profile by 27 percentage points (pp) and raised the probability of securing a job contract by nearly 6 pp.

3. Most people do not get more than one contract and there is no sustained success on livelihoods.

While the training boosted online freelancing engagement, it did not translate into sustained success on the platforms. Treated participants received, on average, only 1.6 online job offers over the year, signed just 0.5 contracts, and earned less than 5% of their total income from freelancing. The training had no significant effect on the number of contracts, income from freelancing, or participants’ intentions to continue freelancing the following year.

Beyond freelancing outcomes, we found no significant effects on broader labour market indicators, such as employment status, number of jobs, formal employment, or monthly income. Taken together, our results suggest no sustained impact of the programme on participants’ livelihoods.

Exploring mechanisms, one possible reason for the lack of sustained impact is poor platform ratings. On online freelancing platforms, clients typically rate workers on a scale from 1 to 5, which serves as a quality signal critical for securing future contracts (Wood et al. 2019). In our sample, both treatment and control groups averaged ratings of around 3 out of 5, whereas the average freelancer rating on Upwork, a leading platform, is 4.9. This discrepancy suggests that although the training helped participants enter the freelancing space, low ratings from initial jobs likely hindered their ability to build a successful online freelancing career.

Policy implications: Further technical training may be necessary to unlock online freelancing opportunities

Our study indicates that while the training programme boosted engagement with online freelancing platforms and led to some early successes, it did not result in sustained improvements in participants’ livelihoods. A similar lack of lasting impact was observed in a prior pilot of the same programme in Haiti (Baptista et al. 2023).

Taken together, our findings suggest that simply helping workers navigate online freelancing platforms may not be enough; they may also need support to bring their technical skills up to a level that is globally competitive. Without this, workers from developing countries may struggle to compete with freelancers from other regions, limiting the effectiveness of such programmes. A recent study by Das et al. (2024) in Bangladesh, which tested the impact of training women in the technical skills needed for online freelancing, suggests that focusing on technical skills training may hold more promise. However, further research in this area is needed.

Our study also highlights that a key challenge for online training programmes is increasing completion rates, especially when the training is asynchronous and there are no penalties for dropping out. In line with other studies, such as Novella et al. (2024), we find that this challenge is particularly pronounced for individuals from poorer households, who likely face additional external barriers to completion.

References

Baptista, D, R Freund, and R Novella (2023), “Entrepreneurial skills training for online freelancing: Experimental evidence from Haiti,” Economics Letters, 232: 111371.

Chan, J, and J Wang (2018), “Hiring preferences in online labor markets: Evidence of a female hiring bias,” Management Science, 64(7): 2973–2994.

Das, N, M R Arman, A Bhattacharjee, M Gomes, and S Mahmood (2024), “Tackling women's unemployment: Evidence from an online freelancing experiment in Bangladesh,” SSRN Electronic Journal.

Datta, N, C Rong, S Singh, C Stinshoff, N Iacob, N Simachew, M Nxumalo, and L Klimaviciute (2023), “Working without borders: The promise and peril of online gig work,” World Bank, Washington, DC.

Fazio, M V, R Freund, and R Novella (2025), “Do entrepreneurial skills unlock opportunities for online freelancing? Experimental evidence from El Salvador,” Journal of Development Economics, 172: 103363.

Hilbert, M, and K Lu (2020), “The online job market trace in Latin America and the Caribbean,” Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, Santiago.

Kässi, O, V Lehdonvirta, and S Fabian (2021), “How many online workers are there in the world? A data-driven assessment,” Open Research Europe, 1: 53.

Lehdonvirta, V, O Kässi, I Hjorth, H Barnard, and M Graham (2019), “The global platform economy: A new offshoring institution enabling emerging-economy microproviders,” Journal of Management, 45(2): 567–599.

Novella, R, D Rosas-Shady, and R Freund (2024), “Is online job training for all? Experimental evidence on the effects of a Coursera program in Costa Rica,” Journal of Development Economics, 169: 103285.

Wood, A J, M Graham, V Lehdonvirta, and I Hjorth (2019), “Good gig, bad gig: Autonomy and algorithmic control in the global gig economy,” Work, Employment and Society, 33(1): 56–75.