Administrative tax and audit data from Rwanda shows that e-invoicing can help increase tax compliance if designed and implemented efficiently and alongside an effective tax audit strategy.

Editor's Note: For more on tax compliance read the VoxDevLit on Taxation and Development.

Revenue mobilisation in developing countries is a persistent challenge with average tax ratios hovering around a mere 15% of GDP and with many countries falling below this benchmark, which is widely considered as the minimal level necessary to meet the urgent Sustainable Development Goals. In response to these challenges, African tax administrations are increasingly embracing reforms involving technological innovations to improve tax collection, enhance service quality, and foster a more growth-friendly taxation environment (ATAF 2021). It is difficult to find another policy shift that has promised as much for tax compliance as digitalisation.

The promise of e-invoicing for improving revenue mobilisation

A key component of the digital transformation is the adoption of electronic invoicing (e-invoicing), a technology that records every sales transaction, creating an accurate and formal link between sellers and purchasers. This technology facilitates the creation of a digital audit trail, allowing tax authorities to trace transactions and verify the authenticity of invoices. It can also enhance tax compliance through improving business record-keeping and reducing unintentional mistakes in tax matters. E-invoicing capability is particularly critical for the Value Added Tax (VAT), which constitutes a substantial portion of tax revenues in Africa - over 35% on average. The credit-invoice mechanism embedded in VAT systems creates an auditable paper trail that acts as a self-enforcement mechanism (discussed in, among others, Pomeranz 2015 and Naritomi 2019), which can be strengthened by e-invoicing. Key to this is that e-invoicing provides (almost) real-time information on transactions to revenue administrations, allowing them (in addition to tax liabilities being defined more accurately) to detect inconsistencies in the reported data along the production chain, and between self-reported and third-party reported tax liabilities. While there are few formal evaluations, there seems to be a consensus that e-invoicing reinforces VAT enforcement capacity.

But there are limitations to e-invoicing in low-capacity contexts

While there are encouraging signs, the success of e-invoicing depends on tax administration capacity and its efficient use. Indeed, recent evidence shows that digital submission of tax information does not necessarily enhance compliance in developing countries due to ineffective cross-checking of transactions and a lack of integration within the tax system (see, for example, Mascagni et al. 2019 and Almunia et al. 2022). The success of e-invoicing, therefore, critically depends on the supporting digital ecosystem and the effectiveness of tax enforcement mechanisms, particularly tax audits.

E-invoicing and tax audits in Rwanda

The introduction of e-invoicing in Rwanda has been considered successful in terms of deployment and increasing revenue collection. But, as with other African countries, it has not been free of problems: interconnectivity with the tax ecosystem, data inaccuracies, incomplete data, being the most critical. This has meant that pre-filling of VAT returns could not be implemented. While prefilling is not immune to manipulation (Chen et al. 2017), the lack of this function means that firms can manipulate their purchases by inflating VAT paid on inputs, a behaviour that has been documented for Ethiopia (see Mascagni et al. 2021). And they can also manipulate other margins, such as, for example, misclassifying goods to VAT exempt or zero-rated categories. In recent research (Kotsogiannis et al. 2024), we analyse the impact of e-invoicing on VAT compliance in Rwanda, focusing, in particular, on the role of this technology in enhancing tax audit effectiveness. Our research also sheds light on the behaviours adopted by firms to reduce tax liabilities as a response to the introduction of e-invoicing and highlights the role of operational audits in mitigating them.

Evaluating the impact of e-invoicing and tax audits in Rwanda

Our analysis utilises administrative tax data on VAT filings and records from multiple tax audit waves from 2012 to 2019, along with information on the adoption of e-invoicing. The adoption of e-invoicing has been staggered with different firms adopting at different times, and this allows us to empirically identify the impact of the digital innovation and audits (using a stacked difference-in-differences approach). From a technical perspective two issues arise (common in these type of empirical investigations): first, firms who have been audited are not randomly selected but their selection depends on risk assessment and, secondly, the adoption of e-invoicing might be related to firms’ noncompliance attitudes. Our empirical strategy addresses these matters by matching each treated firm (audited or adopting e-invoicing) with a set of observationally equivalent control group members (untreated firms). By holding the confounding factors constant, the difference between the outcome variable of treated firms and matched controls provides a direct estimate of the treatment effect (the impact of the audit and e-invoicing adoption on treated firms).

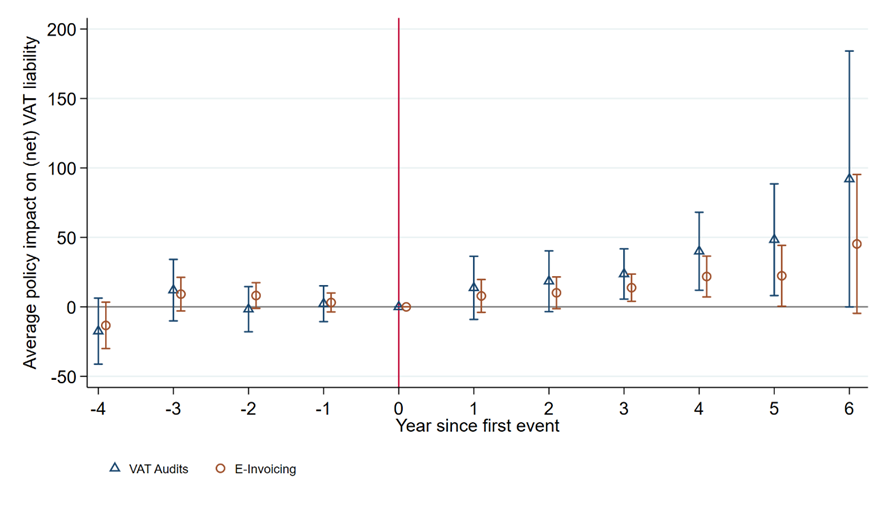

Figure 1: Aggregate dynamic response to VAT audits and e-invoicing.

Note: The figure reports the estimates of the period-specific policy effects on net VAT liability for audits and e-invoicing separately. Confidence intervals of the estimates are reported. For details see Kotsogiannis et al. (2024).

The main variable used to measure the compliance impact is the net VAT liability reported by firms. For this margin, the figure presents the average impact on (net) VAT liability caused by each ‘treatment’ separately (tax audits and e-invoicing adoption) showing that before the treatment (‘standardised’ to be in year 0), the firms selected for future treatment were identical in their reporting behaviour to those not selected for treatment, as indicated by the lack of significant differences between these groups in their reporting prior to the treatment. Significance in post-treatment estimated effects provides evidence of audits and e-invoicing adoption impacting compliance, in terms of the net VAT liability reported by firms.

To put this into context, when these enforcement policies are analysed separately, they have an aggregate increase (following the policy intervention) in the net VAT liability declared of about US$27,000 for audits and about $11,000 for e-invoicing adoption. And these effects tend to persist. Focusing now on the joint deterrence effect of VAT audits and e-invoicing, the results suggest that the impact on compliance is mostly driven by tax audits performed on firms adopting the e-invoicing system. Interestingly, the only audits leading to a significant improvement in VAT compliance are those involving firms employing e-invoicing which yield a net combined effect on future VAT payments of about $33,400. But e-invoicing’s impact is also greater when combined with audits. All this suggests that the information flow provided to the Rwanda Revenue Authority through the digital trail improves the audit performance in terms of deterrence. Presumably, this impact is driven by firms internalising in their compliance strategy the fact that the paper trail of transactions provides a good source of information for the Rwanda Revenue Authority during an audit, thereby making those firms less willing to take risk in non-compliance than they otherwise would. Importantly, the results also suggest that the adoption of e-invoicing provides only a limited improvement in compliance. For compliance to improve e-invoicing it should be supported by enforcement measures.

Over-reporting of VAT input and goods misclassification

To reduce their tax liabilities, firms might misclassify goods and services as VAT exempt but also inflate the VAT paid for the purchase of the inputs. Our research investigates these two margins showing that treated taxpayers tend to initially respond to e-invoicing and tax enforcement by over-reporting their input VAT to reduce their tax liability. This behaviour, however, is mitigated when tax audits are strengthened by the use of e-invoicing, providing evidence that e-invoicing and tax enforcement through audits are complements as instruments. A similar pattern emerges for exempt VAT sales, but this effect cannot be identified with the desired precision.

Digitalisation and the road ahead

One reason for the poor revenue performance of many developing countries is that their tax administrations commonly lack effectiveness in their core functions - registration of taxpayers, assessment of their liability, and collection of taxes - and so compliance is low. Digitalisation offers potentially transformative opportunities for improving tax compliance and revenue mobilisation. But for tax administrations operating under weak capacity, the implementation of technological solutions should be carefully assessed. This is an important issue and one that is directly related to the design and effectiveness of tax auditing and capacity building in tax administrations. The results do not suggest that digitalisation is not a good strategy for enhancing compliance. To the contrary, it is an enabling factor, but one that needs to be designed and implemented effectively within an ecosystem that records all information through the business-to-business and business-to-consumer transactions accurately. This journey for developing countries is a long and expensive one; every step taken needs to be thoroughly evaluated.

References

Ali, M, A Shifa, A Shimeles, and F Woldeyes (2021), “Building fiscal capacity in developing countries: Evidence on the role of information technology,” National Tax Journal, 74: 591–620.

Almunia, M, J Hjort, J Knebelmann, and L Tian (2022), “Strategic or confused firms? Evidence from ‘missing’ transactions in Uganda,” The Review of Economics and Statistics, 1–35.

ATAF (2021), “Efficient Implementation and maintenance of ICT tax systems in Africa: Compilation of good practices, success stories, and lessons learnt,” ATAF Research Publications.

Barreix, A D, R Zambrano, M P Costa, A A Da Silva Bahia, E Almeida de Jesus, V Pimentel de Freitas, F Barraza, N Oliva, M Andino, A Rasteletti, C Drago, G Cuentas, M Paredes, J Pazos, L Canales, R Campo, L Castiñeira, G González, J F Redondo, A F Ferreira de Almeida, K Hernández, J Robalino, J Ramírez, J P Anjos Andrade, N Rodrigues Gonçalves (2018), “Electronic invoicing in Latin America,” Available at: https://publications.iadb.org/en/electronic-invoicing-latin-america.

Chen, J, G Grimshaw, and G Myles (2017), “Testing and implementing digital tax administration,” Chapter 5, in S Gupta, M Keen, A Shah, and G Verdier (eds.), Revolution in Public Finance, International Public Finance, Washington D.C.

Eissa, N, and A Zeitlin (2014), “Using mobile technologies to increase VAT compliance in Rwanda,” Mimeo, McCourt School of Public Policy, Georgetown University.

Kotsogiannis, C, L Salvadori, J Karangwa, and M Theonille (2024), “Do tax audits have a dynamic impact? Evidence from corporate income tax administrative data,” Journal of Development Economics, 170: 103292.

Kotsogiannis, C, L Salvadori, J Karangwa, and I Murasi (2024), “E-invoicing, tax audits and VAT compliance,” BSE Working Paper 1454.

Mascagni, G, A T Mengistu, and F B Woldeyes (2021), “Can ICTS increase tax compliance? Evidence on taxpayer responses to technological innovation in Ethiopia,” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 189: 172–193.

Mascagni, G, D Mukama, and F Santoro (2019), “An analysis of discrepancies in taxpayers’ VAT declarations in Rwanda,” ICTD Working Paper 92.

Naritomi, J (2019), “Consumers as tax auditors,” American Economic Review, 109: 3031–3072.

OECD (2022), “Tax Administration 3.0 and Electronic Invoicing,” Available at: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/publication/2ffc88ed-en.

Pomeranz, D (2015), “No taxation without information: Deterrence and self-enforcement in the Value Added Tax,” American Economic Review, 105: 2539–2569.