Minimum wage increases in China are spent rather than saved, and are not associated with increased unemployment. In households with children, a significant portion of the additional income is allocated to healthcare and education.

How labour market policies, such as minimum wages, impact household welfare has been a longstanding topic of discussion among economists and policymakers (Rama 2001, Comola and De Mello 2011, Fang and Lin 2015, Del Carpio et al. 2019). In the current global context, where wage inequality, which challenges social cohesion, and the pursuit of sustainable living standards have become important social policy objectives, understanding the influence of minimum wage adjustments on consumption patterns is particularly valuable. Our recent research (Dautovic, Hau and Huang 2024) contributes to this policy discussion with a nuanced analysis of how minimum wage hikes in China affect the consumption behaviour of low-wage households.

Background on China's Minimum Wage Policy

China's minimum wage policy is a key element of the country's labour market framework, affecting one of the world's largest workforces, estimated at nearly 800 million workers. This policy is distinctive due to its scale and decentralised implementation, with minimum wages determined at the county level. Consequently, a diverse landscape of wage floors exists across China’s extensive geography.

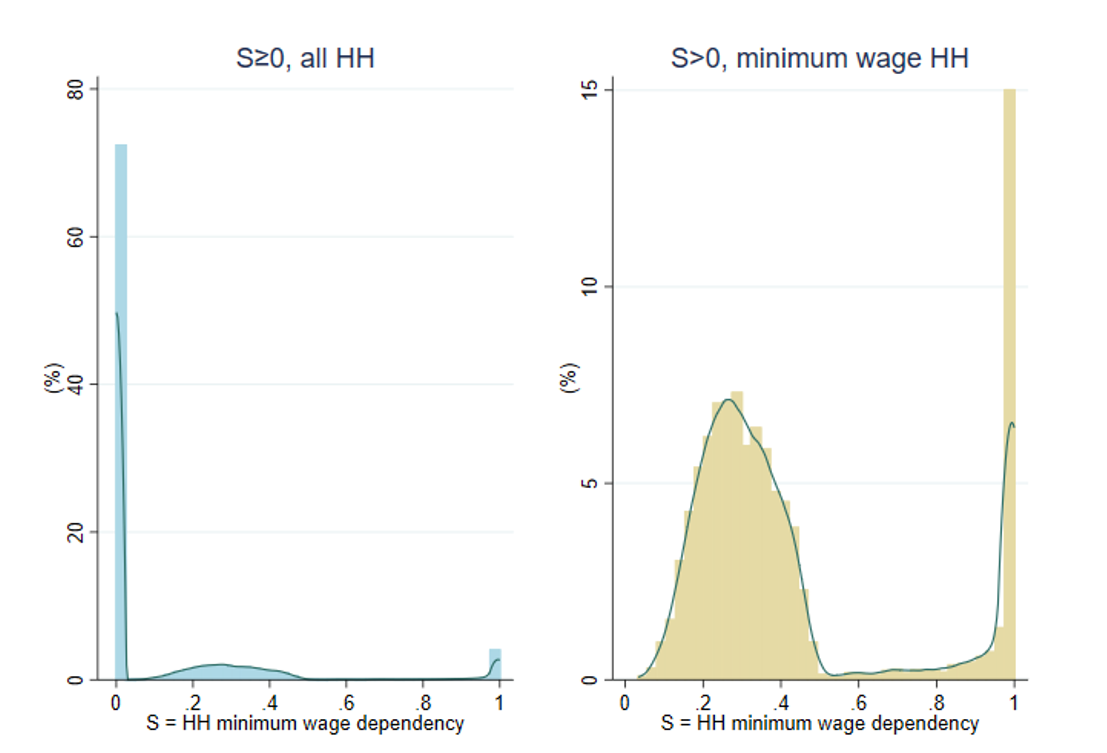

Figure 1: Minimum wage and income share in China

Notes: The chart plots the distribution of the share S of household income coming from minimum wages as defined for N=73164 households-years. The LHS plot features data for all the households, including those without minimum wage income S=0 for which we have N=53054. The RHS plots the distribution of S conditional on S>0, that is N=20110

Minimum wage policies were first established in China in 1994, coinciding with a wave of economic liberalisation and the transition towards a mixed economy with a burgeoning private sector. The policy initially faced challenges, such as the lack of adjustment mechanisms for inflation and economic conditions, as well as issues with enforcement and compliance. A significant reform of the Minimum Wage Regulations (MWR) was introduced in 2004, mandating that minimum wages be indexed to the cost of living and adjusted at least biennially to ensure they meet basic living standards. This reform also aimed to strengthen enforcement and compliance by increasing penalties for non-compliance.

Capturing the impacts of minimum wages in China

The frequent adjustments to minimum wages, in response to economic growth and inflation, provide a rich source of variation for studying the policy's effects. Between 2002 and 2009, we identify over 13,874 minimum wages changes across China's 2,183 counties. This large variation offers a unique opportunity to analyse the impact of these changes on the consumption behaviour of households.

Our research explores the effects of China's minimum wage policy on the consumption patterns of low-wage households, utilising a large dataset from the Chinese Urban Household Survey (UHS), which includes comprehensive panel data on household income and consumption from 2002 to 2009. By examining the exogenous variation in income resulting from the 13,874 minimum wage changes, our study assesses its influence on household consumption behaviour. We focus on the marginal propensity to consume (MPC) out of minimum wage income increases, which measures how much of household’s additional income after a minimum wage increase is used for consumption. This consumption measure is central to evaluating the effectiveness of minimum wage policies in improving household welfare.

How do minimum wage increases impact households in China?

One of our key findings is that an increase in the minimum wage leads to a significant rise in consumption for households that heavily depend on minimum wage income. Specifically, we find that the MPC is close to one for these “treated” households. This indicates that every additional yuan of income from a minimum wage hike is fully spent rather than saved. The incremental consumption effect is particularly pronounced for households with children, where a significant portion of the additional income is allocated to healthcare and education—expenditures that can be expected to yield long-term benefits for the household's well-being and economic prospects.

Another important finding of the paper is the absence of unemployment effect. Notwithstanding frequently voiced concerns that higher minimum wages could lead to job losses, our study finds little evidence to support such fears in the case of China. Even among the most vulnerable groups, such as migrant workers, our research does not reveal any substantial increase in unemployment risk associated with minimum wage increases.

A recent labour literature summarised by Neumark and Corella (2020) relates this absence of unemployment effects to the low bite of China's minimum wages, i.e. the minimum wage is at a relatively low level compared to the median wage. The average ratio of the minimum wage to the median wage is around 20%, and therefore much lower than the 40-50% in many developed countries. In other words, the minimum wage is set at a low level that is less likely to cause significant labour market disruptions.

Implications for minimum wages in China and other developing economies

The findings of this study offer clear guidance for policymakers in China and other developing economies about minimum wages and their adjustment. The robust evidence of a high marginal propensity to consume (MPC) among low-wage households suggests that minimum wage increases can effectively raise the living standards of the poorest households by boosting their purchasing power. This effect is particularly significant for households with children, who are likely to invest the additional income in health care and education—key areas that promote long-term welfare and human capital development. Consequently, policymakers should view minimum wage policies not only to address immediate income inequality, (Engbom and Moser 2020), but also as an investment in the future well-being and productivity of their citizens.

Moreover, the absence of significant unemployment effects in this study indicates that the current level of minimum wages in China is well below the threshold that generates substantial job losses. This finding should reassure policymakers that moderate increases in minimum wages are unlikely to harm the overall employment situation - even among vulnerable groups such as migrant workers. It also suggests that the benefits of higher wages can be realised without undermining the stability of the labour market. As such, policymakers can confidently adjust minimum wages to reflect changes in the cost of living and economic conditions. This ensures that the minimum wage remains an effective tool for protecting the income and consumption levels of the lowest-paid workers.

References

Comola, M, and L De Mello (2011), “How does decentralized minimum wage setting affect employment and informality? The case of Indonesia”, Review of Income and Wealth, 57(s1): S79–S99.

Del Carpio, X V, J Messina, and A Sanz-de Galdeano (2019), “Minimum wage: does it improve welfare in Thailand?”, Review of Income and Wealth, 65(2): 358–382.

Engbom, N, and C Moser (2020), "Earnings Inequality and the Minimum Wage: Evidence from Brazil" VoxDev.org.

Fang, T, and C Lin (2015), “Minimum wages and employment in China”, IZA Journal of Labor Policy, 4(1): 1–30.

Neumark, D, and L F Munguía Corella (2020), “Do minimum wages reduce employment in developing countries? A survey and exploration of conflicting evidence”, VoxDev.org.

Rama, M (2001), “The consequences of doubling the minimum wage: the case of Indonesia”, Industrial & Labor Relations Review, 54(4): 864–881.