A nationwide alcohol ban in South Africa reduced violent crime and injury-related deaths, offering critical lessons for public policy.

The multifaceted influence of alcohol on society

Alcohol use is deeply woven into the fabric of many human societies. From casual social gatherings to important cultural and religious ceremonies, it plays a role as a social lubricant. People often associate moderate consumption with relaxation, stress relief, and fostering social connections. However, alcohol also poses serious risks, particularly when consumed excessively.

Researchers have long pointed to the association between alcohol and numerous social harms. These include adverse health effects, injuries from inter alia motor vehicle collisions and violence, reduced productivity at work and risky sexual behaviour (Carpenter and Dobkin 2011, Taylor and Rehm 2012, Rehm et al. 2017, Griswold et al. 2018, WHO 2019). It is often individuals who do not consume alcohol who bear the brunt of these harms, meaning that negative externalities are imposed either directly (as in the case of interpersonal violence) or indirectly (as in the case of public health insurance). Given the widespread acceptance of alcohol in everyday life and the significant harms it can cause, policymakers around the world face a difficult challenge when it comes to designing alcohol regulation. Striking a regulatory balance that reduces harms without unduly restricting the freedoms of those who see alcohol as a positive part of their lives is no easy task. This challenge is made even more difficult by the lack of precise information about the full extent of alcohol’s influence in society as well as the political influence the alcohol industry wields in many countries. The growing body of empirical research can help to inform this ongoing debate by providing valuable insights into the true impact of alcohol consumption at a societal level.

Existing evidence on the impacts of alcohol in society

The World Health Organization estimates that alcohol is responsible for 5.3% of all global deaths, with nearly one million of these deaths being related to injuries (WHO 2019, Shield et al. 2020). To help improve our understanding of the channels through which alcohol exerts its influence and guide alcohol policy, researchers have produced a large body of empirical research linking alcohol to a range of harmful behaviours and outcomes.

One strand of work has aimed to establish a causal link between particular policy changes affecting alcohol availability and important outcomes. For example,

- Changes in underage drunk driving laws or minimum drinking age laws (Wagenaar and Toomey 2002, Carpenter and Dobkin 2009, 2011, 2017).

- Changes in laws regulating permitted alcohol trading hours (Biderman et al. 2010, Green et al. 2014, Marcus and Siedler 2015, 2018).

This has generated valuable insights regarding the influence of important alcohol control policy margins (e.g. restrictions on young adults on the verge of legal adulthood or restrictions on late-night alcohol purchases). The evidence indicates that alcohol control policies are effective in reducing short-run social harms on these margins.

The regulation of alcohol is not a recent phenomenon, with the Temperance Movement and Prohibition in the United States a salient example. Research examining the impact of state and federal prohibition statutes in the United States has presented a mixed picture regarding their impact on public health and safety (Miron and Zwiebel 1991, Miron 1999, Dills and Miron 2004, Owens 2011, Livingston 2016, Law and Marks 2020). The mixed results may be a consequence of the fact that the policy changes unfolded over an extended period of time and many other changes occurred in society in parallel. This makes it challenging to isolate the effects of the alcohol regulations from other societal changes occurring at the time.

Alcohol prohibition and behaviour: Evidence from South Africa

Researchers rarely have the opportunity to cleanly isolate the influence that alcohol consumption has at a national level. South Africa’s sudden five-week alcohol sales ban in July 2020, however, provides such an opportunity. The ban was introduced with the aim of reducing alcohol-related injuries and freeing up hospital resources for COVID-19 patients. It was introduced abruptly and unexpectedly at a time when other societal factors were largely constant. These conditions make it a suitable natural experiment to investigate the short-term effects of removing alcohol from society.

Our research (Barron et al. 2024) uses this opportunity to document causal evidence regarding the influence of alcohol on violent behaviour and injury-related deaths. We show that the policy occurred largely in isolation from other COVID-related changes in society and discuss why other contemporaneous factors are unlikely to be able to explain the results.

How did South Africa’s alcohol ban affect violent behaviour and injury-related deaths?

We find that the alcohol ban reduced injury-induced mortality in the country by at least 14%, with the majority of this reduction occurring among men. This is unsurprising, given that nearly four out of every five injury-induced deaths in South Africa are male and men are significantly more likely to engage in heavy episodic drinking (WHO 2019, Roomaney 2023). These societal patterns are not unique to South Africa and are mirrored in other countries, such as Brazil and Russia (Starodubov et al. 2018, Gawryszewski and Rodrigues 2006, WHO 2019). As a result, our findings may be relevant for understanding alcohol’s influence in other countries, particularly those where there are high rates of heavy drinking and high levels of injury deaths.

In addition to analysing injury deaths, we also document a sharp parallel drop in violent crimes during the ban, with homicides decreasing by 21%, assaults by 33% and reported rape cases by 19%. These findings indicate a tight link between alcohol and aggressive behaviour and align with existing evidence connecting alcohol consumption to violence (Darke 2010, Kuhns et al. 2011, 2014). Alcohol control regulation may therefore be an effective policy in contexts with high rates of violence.

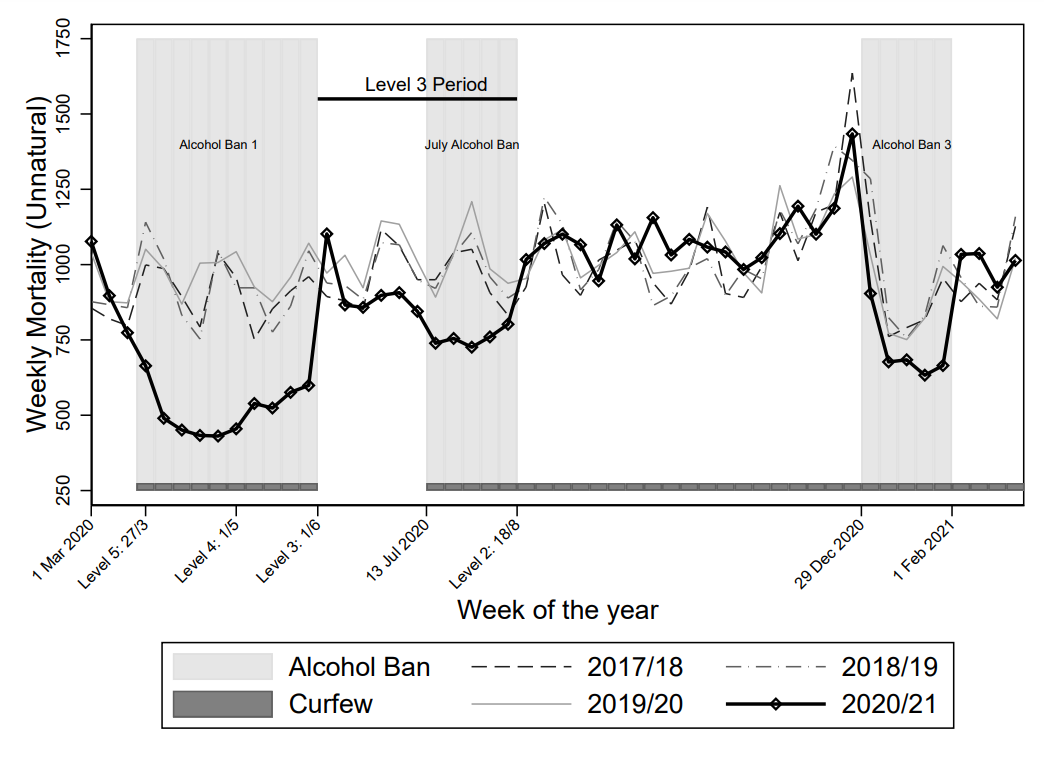

Figure 1: The timeline of alcohol bans and weekly injury mortality in South Africa

Note: This figure shows weekly injury mortality in South Africa. The dark line portrays mortality between 1 March 2020 and 28 February 2021. The shaded areas show that three national alcohol bans took place during this period. The second, the July Alcohol Ban, is the focus of the analysis in Barron et al. (2024), because, unlike the other bans, it was sudden and unexpected and occurred while other factors in society remained relatively stable. The figure shows that all three alcohol bans were associated with drops in injury mortality relative to the pattern observed in previous years (indicated by the lighter lines). Notice that the zigzag pattern observed in previous years is consistent with a monthly cycle of injury mortality, with higher mortality close to the end of the month (especially on weekends). Source: reproduced from Barron et al. 2024.

Policy implications: A case for evidence-based alcohol regulation

These findings build on and expand this important research area, thereby informing the design of evidence-based policy. While no single study can guide policy on its own, the collection of insights generated by this research offers a richer understanding of how best to reduce alcohol-related harms without diminishing its social benefits.

The results of our research indicate that alcohol causes significant short-term harm through its effects on behaviour. Importantly, this study focused solely on these immediate behaviour-mediated impacts and did not look at longer-term health impacts, such as liver cirrhosis and cancer, suggesting that the overall harm may be even greater. The evidence paints a clear picture of the substantial social harm caused by alcohol which deserves careful attention, especially in societies with high rates of interpersonal violence and binge drinking.

The global evidence underscores the need for context-specific approaches to alcohol regulation (WHO 2019). While the South African ban was highly effective in the short term, sustained reductions in alcohol-related harm may require a combination of measures, such as stricter enforcement of existing laws, public health campaigns and targeted interventions for heavy drinkers. This multi-faceted approach, informed by rigorous research, can help governments strike the right balance between public health priorities and individual freedoms.

References:

Barron, K, C D H Parry, D Bradshaw, R Dorrington, P Groenewald, R Laubscher, and R Matzopoulos (2024), "Alcohol, violence, and injury-induced mortality: Evidence from a modern-day prohibition," The Review of Economics and Statistics, 106(4): 938–955. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_01228.

Bates, G (1918), "The relation of alcohol to the acquisition of venereal diseases," Public Health Journal, 9(6): 262–267.

Biderman, C, J M De Mello, and A Schneider (2010), "Dry laws and homicides: Evidence from the São Paulo Metropolitan Area," Economic Journal, 120(543): 157–182.

Blocker, J (2006), "Did Prohibition really work? Alcohol prohibition as a public health innovation," American Journal of Public Health, 96(2): 233–243.

Carpenter, C, and C Dobkin (2009), "The effect of alcohol consumption on mortality: Regression discontinuity evidence from the minimum drinking age," American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 1(1): 164–182.

Carpenter, C, and C Dobkin (2011), "The minimum legal drinking age and public health," Journal of Economic Perspectives, 25(2): 133–156.

Carpenter, C, and C Dobkin (2017), "The minimum legal drinking age and morbidity in the United States," The Review of Economics and Statistics, 99(1): 95–104.

Darke, S (2010), "The toxicology of homicide offenders and victims: A review," Drug and Alcohol Review, 29(2): 202–215.

Dills, A K, and J A Miron (2004), "Alcohol prohibition and cirrhosis," American Law and Economics Review, 6(2): 285–318.

Emerson, H (1932), "Prohibition and mortality and morbidity," Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 163(1): 53–60.

Green, C P, J S Heywood, and M Navarro (2014), "Did liberalising bar hours decrease traffic accidents?" Journal of Health Economics, 35: 189–198.

Kuhns, J B, M L Exum, T A Clodfelter, and M C Bottia (2011), "The prevalence of alcohol-involved homicide offending: A meta-analytic review," Homicide Studies, 15(2): 122–143.

Kuhns, J B, M L Exum, T A Clodfelter, and M C Bottia (2014), "The Prevalence of Alcohol-Involved Homicide Offending: A Meta-Analytic Review," Homicide Studies, 18(3): 251–270.

Law, M T, and M S Marks (2020), "Did early twentieth-century alcohol prohibition affect mortality?" Economic Inquiry, 58(2): 680–697.

Livingston, B (2016), "Murder and the black market: Prohibition’s impact on homicide rates in American cities," International Review of Law and Economics, 45: 33–44.

Marcus, J, and T Siedler (2015), "Reducing binge drinking? The effect of a ban on late-night off-premise alcohol sales on alcohol-related hospital stays in Germany," Journal of Public Economics, 123: 55–77.

Marcus, J, and T Siedler (2018), "Do changes in bar closing hours affect alcohol-related hospital stays?" Journal of Public Economics, 163: 28–45.

Miron, J A (1999), "Violence and the U.S. prohibitions of drugs and alcohol," American Law and Economics Review, 1(1): 78–114.

Miron, J A, and J Zwiebel (1991), "Alcohol consumption during prohibition," American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings, 81(2): 242–247.

Owens, E G (2011), "Are underground markets really more violent? Evidence from early 20th century America," American Law and Economics Review, 13(1): 1–44.

Phillips, R (2014), Alcohol: A History, UNC Press Books.

Rehm, J, G E Gmel Sr, G Gmel, O S Hasan, S Imtiaz, S Popova, C Probst, and P A Shuper (2017), "The Relationship between Different Dimensions of Alcohol Use and the Burden of Disease: An Update," Addiction, 112(6): 968–1001.

Roomaney, R A, S Mhlongo, B Dekel, A Ketelo, L Martin, S Ntsele, et al. (2023), "The third Injury Mortality Survey: A national study of injury mortality levels and causes in South Africa in 2020/21," South African Medical Research Council.

Taylor, B, and J Rehm (2012), "The relationship between alcohol consumption and fatal motor vehicle injury: High risk at low alcohol levels," Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 36(10): 1827–1834.

Wagenaar, A C, and T L Toomey (2002), "Effects of minimum drinking age laws: Review and analyses of the literature from 1960 to 2000," Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement, s14: 206–225.

Warburton, C (1932), The Economic Results of Prohibition, New York: Columbia University Press.

WHO (2019), Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health 2018, World Health Organization.